05 Aug The Joy of Discovery

CODY, WYOMING-BASED ARTIST MIKE “M.C.” Poulsen remembers the genesis of his epic Yellowstone Waterfall Project. An accomplished painter since his early 20s, Poulsen was attending an author’s presentation of the then-newly released book, The Guide to Yellowstone Waterfalls and their Discovery, when he was hit with a memory of visiting Niagara Falls as a youngster. After the presentation, he left with a strange but welcome sense of purpose: Although Yellowstone’s waterfalls had been painted before, most notably by Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran in the late 1800s, no one had painted the major ones, or the undiscovered ones. Poulsen wanted to be the first.

“I wanted to tell the Yellowstone story in my own way, I guess,” says Poulsen, who is now 10 years into the project. Throughout his journey, he has received support through the organization Yellowstone Forever and had a Wyoming PBS crew follow him for two years to document his vision and creative process. The resulting documentary, “Painting the Falls of Yellowstone,” premiered in June 2017, and is still available online. But since that time, for Poulsen, the Waterfall Project has just kept moving forward.

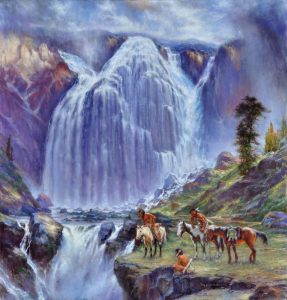

Union Falls | Oil | 24 x 20 inches

The birth of Poulsen’s magnum opus goes back to his childhood, like a winding trail marked by moments when serendipity and choice — especially in the face of a challenge — collided on his path through life. “I was always interested in art,” says Poulsen, who remembers when a kindergarten teacher in his Akron, Ohio, elementary school ridiculed his art project in front of the class. In what would be a lifelong response to adversity — something inherited from his stalwart military father, perhaps — Poulsen declared he’d be a better artist than any of his classmates.

By all accounts he has succeeded, and he has sold works as he’s created them from his 20s onward. Accolades include the People’s Choice Award at the 2010 Buffalo Bill Center of the West Art Show and Sale, where he served as an artist in residence in 2017, and the 2011 Wyoming Governor’s Arts Award. However, Poulsen’s definition of success is not tied to commerce. “I realized that you have to be happy within yourself, follow your own intuition, and not worry about what sells and what doesn’t,” he says. “As soon as the galleries were asking for certain types of paintings, I ran. That never works out.”

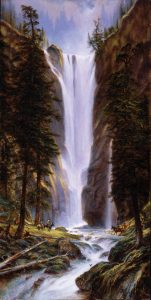

Lost Falls | Oil | 40 x 22 inches

Throughout his life, Poulsen has received encouragement from numerous sources. His father displayed copies of Carl Bloch’s artwork, and Poulson would wander around the Akron Art Museum (formerly the Akron Art Institute) while his mother worked nearby. There, the staff gave him drawing materials and nudged him to learn-by-copying, which improved his confidence and skills simultaneously. “It all just seemed so natural that I was attracted to all types of art with no judgement or critique,” says Poulsen, who played around with sculpting, but found his niche in drawing, painting, and working with color.

The colors of his youth changed, and his whole world changed, when his father sold his insurance company and purchased 15,500 acres of South Fork, Wyoming, ranch land in the early 1960s. “During my first visit to Cody at 11, I thought all kids rode horses to school,” says Poulsen. “I loved the wide-open spaces, and the stars and skies were breathtaking.” He decided then that he would always live in the West.

Citadel of Asgard Falls | Oil | 20 x 12 inches

At age 13, Poulson started following in the footsteps of artists like Charles Russell and Harry Jackson, whose infatuation with the West also began when they were teenagers. On the ranch, he lived in a bunkhouse with his three younger brothers adjacent to the family home. In addition to keeping the bunkhouse in tip-top shape under the watchful eye of his father, a former Marine drill sergeant, the boys worked hard. “I would show up for work at 5 a.m.,” says Poulsen. He helped feed 80 to 100 horses each morning and care for 500 to 1,000 head of cattle. In his spare time, he explored the wilderness and sketched.

When he was 17, Poulsen joined the Marines as a military policeman. He was stationed first in Georgia, and then in Virginia, where he visited museums in nearby Washington, D.C., sketchbook in hand. While stationed in Hawaii, he met and studied privately under Larry Roberson, an artist whom Poulsen credits with helping establish his foundational processes. Poulsen’s choice for his first assignment? A copy of Thomas Moran’s Mountain of the Holy Cross, which he sent to his mother upon completion.

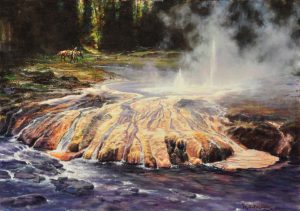

Three Forks Cauldron | Oil | 18 x 24 inches

After the military, Poulsen enrolled at Arizona State University, thinking he needed an art degree. His professor, however, told him there was nothing college could teach him about painting that he didn’t already know or couldn’t learn on his own. Since he had already been showing his work at several galleries in Scottsdale, she advised him to just do the work and keep painting.

That, along with his father’s advice to limit distractions and behave professionally, served him well, even through personal adversity. “Nothing like cancer or death to cause you to question life’s trials,” says Poulsen, who had an easel in his hospital room while battling leukemia. “I am not a mood painter,” he says. “I put everything behind me and move forward. It’s all you can do.” When he lost his eyesight for five months after a doctor misprescribed medication, he and wife Shauna’s exploration of alternative medicine and other support, combined with Poulsen’s sheer grit, saw him through it all.

Artist M.C. Poulson works on-site in Yellowstone’s backcountry, often sketching and then painting the waterfalls.

Other help came in the form of mentorships from fellow artists. Wyoming artist James Bama critiqued his early works in the ‘70s, saving him years of trial and error. “His output was incredible, and I had tremendous respect and love for what he has done for art,” says Poulsen, who also took a class with Western art legend Howard Terpning and the Texas-based painter Griff Carnes.

Poulsen also taught classes, including the Whitney Western Art Museum’s “Learning From the Masters” class, which he did for free for nine years as a way to give back. Drawing on his own experiences, Poulsen instructed his students to learn-by-copying.

When it comes to painting yellowstone’s waterfalls, Poulsen collaborates with outfitters — including his son — to get into the backcountry. There, he works on-site, taking photographs for reference only, and creating several sketches to figure out the composition. This is especially true for his larger canvases, which can reach 8 to 9 feet. “It’s a lot of canvas to cover,” says Poulsen, who follows a fundamental approach: “Everything is related to the whole — simplify.”

Poulson’s Waterfall Project will be featured in exhibitions around the country, beginning in 2021 at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia.

Poulsen’s initial plan was to paint as many of Yellowstone’s waterfalls as possible, and to date, he’s honed the list to around 50 works. His first major exhibition of the Waterfall Project will be featured at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, in 2021, moving then to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody in 2022.

Poulsen still feels the resounding joy of discovery, and claims to be at the peak of his abilities as an artist. “I’m here at the right time and the right place,” says Poulsen. “I am glad I was inspired. Seems like I was always headed in this direction, and I hope it will all be seen in the right way. If you paint from the heart, may it find its way to the heart.”

No Comments