21 Aug Images of the West: The Fifth Row, An Acoustic Tour of Historic Theaters

IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NIGHT A MAN SITS ALONE with a guitar in a turn-of-the-century theater with only ghoses of the past as an audience. The seats will remain empty as the classical acoustic guitarist, Stuart Weber — intent on the music, the mood and the room — prepares to play and record for the “fifth row” or the ear of the room.

“The focus was not on me. It was an intense relationship with the instrument and the setting,” Weber said of the groundwork for his upcoming album.

Weber’s other albums, among them Under the Big Sky: Guitar Anthology and Departures, plus Evening in the Country are clean and sharp. Aberrant sounds and background are eliminated and those recordings were well polished before release. But this time he was not interested in doing another studio recording.

This time, Weber was reaching for something other than simply perfection in the recording studio. His goal was twofold: the intimacy with his guitar and a celebration of new recording venues. Ever the innovator, Weber set out to make history by following it.

Originally, the idea was to select a 10-year period of western migration and follow the trail recording in schoolhouses, cabins, bars, banks and hotels. Discovering that these structures would not “record” well, Weber decided on historic theaters for their natural acoustic quality. The explosive growth of the late 19th and early 20th century out West saw a crop of opera houses spring up to cater to the interests of citizens far removed from the cultural amenities of the Eastern states. Many still stand in towns across the Rocky Mountain states.

To identify possible theaters, Weber contacted the arts councils in several Western states. These councils oversee general arts in an area and often write grants for preserving the old theaters. He gave them his general criteria for recording. First, the theater had to be saved by local volunteers and in a restoration period; and second, it had to have historical significance. After investigating venues in several states, he chose five in his home state of Montana, two each in Idaho and Colorado and one each in Utah and Wyoming.

He found that preservation of the past was a driving force in these small communities and keeping the theaters viable was an important component. Weber realized that if it weren’t for grass roots initiatives, many of these theaters were going to be torn down and turned into parking lots. Many were dilapidated and neglected, but managing to stay alive through sheer volunteer power.

“I marvel at the commitment these communities have and their dedication to saving a building … not just the building, but what it stands for.”

With his equipment and instrument at the ready, Weber set out for his chosen venues. At first, attempts to record during the day, were unsuccessful, because the sounds of commerce, like big rigs or motorcyclists seeped into the recording sessions. Working with sound engineers and a customized pair of microphones to record the guitar and the special acoustic qualities of each theater solved one problem. However, seven of 11 completed recordings had to be dumped causing a one-year delay in finalizing the recording.

Eventually, in order to isolate each theater from the chaos and noise of everyday life, Weber found it was best to record his music at night. The process became relatively simple, he claims, with great equipment and a quiet atmosphere, the theater could be “heard.”

At last, with his wagon packed full of new recording equipment, Weber embarked on a pilgrimage, driving from Montana to the four other states in the Rocky Mountains. The long distances gave Weber time for reflection. “I was following some of the same ground the vaudeville acts did as they entertained along the mining circuit,” Weber muses.

Along the way he discovered that many theaters, across the country share a remarkable story. They have been saved from the wrecking ball by a few volunteers, dedicated to preservation and to bringing live entertainment back to their community. These buildings that once united pioneer communities, do so again today. Weber discovered that the architects of the American frontier designed artful buildings and were also great sound engineers who installed acoustics which still resonate for today’s audiences.

On the road, Weber fell into a ritual to prepare for his recording sessions. In the late afternoon, mics were set and levels tested. He ate an early dinner, drew the hotel curtains and slept from 7 p.m. to midnight.

“If my recording was going to succeed, it would have to be while the town slept. While taking every precaution to avoid street noises from bleeding into the theater, I did nothing to filter out the creaking and popping noises the theater itself made as it cooled in the night air. In fact, I welcomed them. I worked alone, with the theater doors locked and all the lights off except for a lamp on stage that could guarantee quiet. Virtually every theater manager warned me of spirits that roamed the balconies and projection rooms, but I had no such encounters.”

Beginning at midnight, Weber did take after take, reaching for perfection.

“The truth is, I loved working in those spaces. I worked until the music and the room cooperated. With engineers, musicians are always aware of everything behind the scenes and the background. This was the room, the guitar and the music. I felt I rekindled a unique relationship with the instrument.”

Just as the town awakened at about 6 a.m., with the session complete, Weber would crank up an eclectic mix on his iPod. “I would blast some rock music through those old theaters and it always sounded good, all the while thinking about the excellent takes the guitar and the theater provided,” he recalls with a smile.

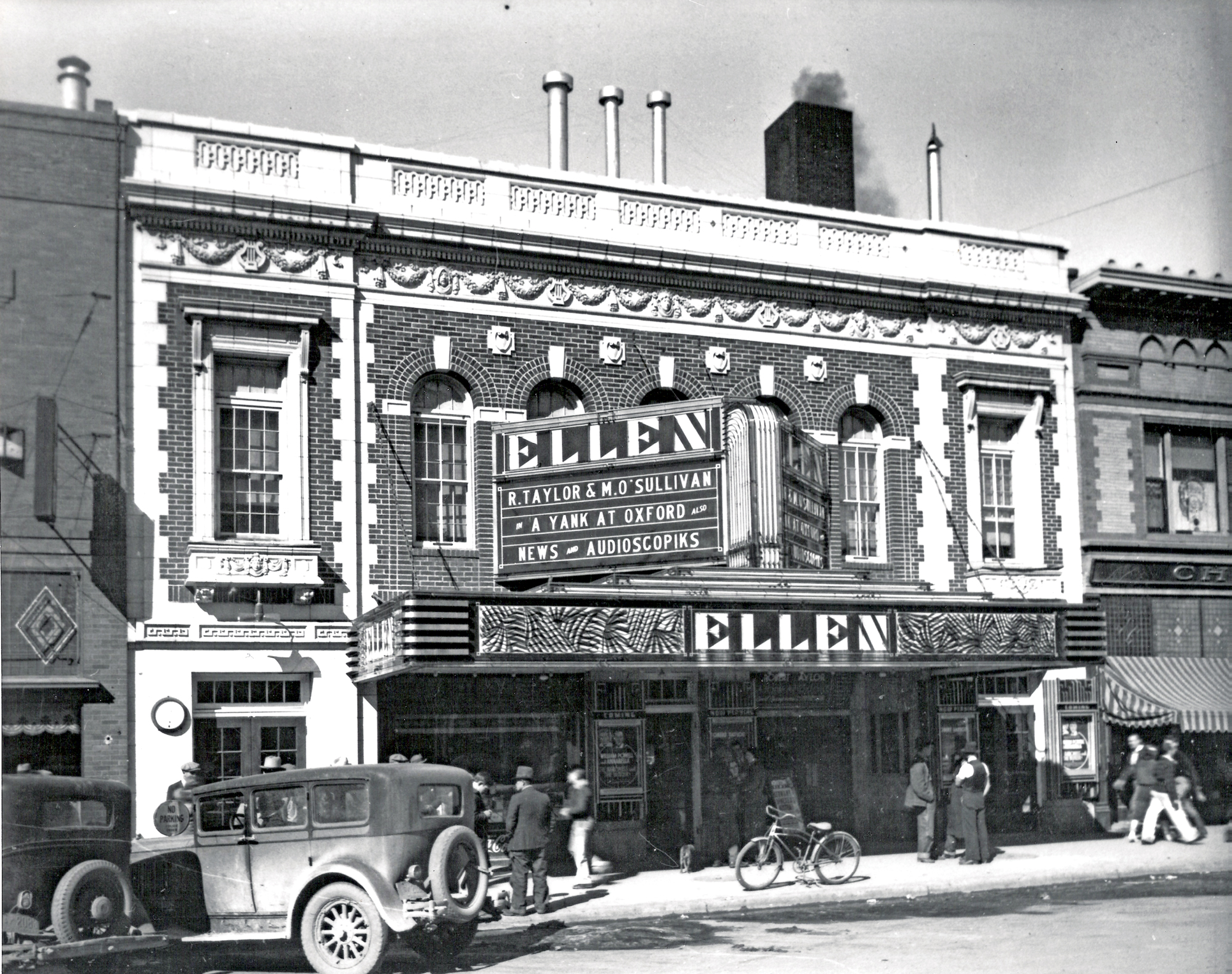

When walking across a 100-year-old stage to set and test microphone levels, it brought to his mind, “It must have been magic for the audience. I know it is for me being on a stage crossed by generations of entertainers. Some famous and some not so.” Bozeman’s Ellen Theater hosted fan dancer Sally Rand, Gary Cooper and Edgar Bergen, the ventriloquist. Not so famous was a vaudeville act with a live elephant. An unidentified magician’s trap door at center stage is still in place at the Phillipsburg Opera house. A 1930s movie projector used for the opening of the Fort Peck movie house reeled through The Richest Days, starring Miriam Hopkins and Joel McCrea.

Originally designed and built as venues for various types of entertainment from plays and symphonies to circus acts and talkies, many 19th and 20th-century theaters were architectural gems. The theaters Weber selected have various architectural styles from classical European revival styles to Art Deco, from Egyptian to Swiss chalet.

When asked how he chose the music for each theater Weber remarks, “I listened. Each room will play differently. I had to work with the acoustics of the environment.” His music also echoes the architecture of the building. At the Wilma theater in Missoula, Weber took a dare to arrange Humoreske by Antonin Dvorak for the guitar. Built in 1920 and once the tallest building in Montana, the Wilma was on the verge of condemnation in the 90s, according to Rick Wishcamper, an owner of the building. After some serious infrastructure work was done, the restoration momentum picked up in the past year and a half. The most noticeable is the new Wilma sign that is a copy of the historic original.

Weber worked with the auditorium and the musical translation over and over until “the music and the theater meshed” and the harmony of the two was perfect for both.

Tango On Spanish Creek, an original composition by Weber, was recorded at the Washoe Theater in Anaconda, considered to be one of the most finely preserved theaters in the country. The rather sedate exterior gives no indication of the silver, copper and gold leaf decorations in the ceiling and walls and of the Art Deco furnishings. Unlike some of the other theaters, the Washoe was built exclusively for the movies. Perhaps it was the paintings of stags on the silk curtain that inspired Weber to write music that heralds the Montana terrain of meadows and streams below the majestic peaks overlooking the Gallatin River.

By “listening” to the theaters, Weber, may have heard more than their acoustic sweet spots, he heard the whispers of all those performers and audiences who came before him.

In 1934, the setting on the plains of eastern Montana was hardly bucolic. More than 11,000 WPA (Works Progress Administration) workers toiled on the Fort Peck dam and most of those work-booted feet tromped up the steps of the Fort Peck Theater to relieve the strain of work and The Depression. No one seemed to care that the architecture was an odd juxtaposition of Arts and Crafts with Swiss chalet. The trick shift, late shift and early shifts came to be entertained by the movies 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It was supposed to be a temporary building, but it turns out the theater was as temporary as the dam. Today, the Fort Peck Theater is still in use and integral to entertainment in Fort Peck.

The Wilson Theater in Rupert, Idaho, originally welcomed live performances and then the talkies. “It was once a thriving community and now the town has few people.” But as Weber says, “It still took on the need to restore the theater. It was in terrible shape and still is in a way. The façade is now restored to the 1920s and with more work to be done. It has been a multi-million dollar endeavor done not with the money from the town but from other sources.”

The town’s 6,000 residents made a commitment to save the theater with donations, yearly local fundraisers and grants. Chris Jackson of the Renaissance Art Center says, “The restoration is being done in phases with only phase three left. In-kind donations alone have totaled $250,000. I have never found a community so determined.” Like most theaters in stages of restoration and renovation Jackson adds, “It has to do with memories, with stability. As we grew up, the Wilson Building was here. It was a part of our lives. All the memories are still there. We are so quick at throwing things away. We have a history and we need to maintain that history.”

The Ellen Theater in Bozeman, Mont., has stood for entertainment since 1918. Built by a prominent local family and named to honor their mother, the Ellen was overlooked and neglected for decades. Thankfully, the Ellen didn’t suffer mid-20th century updates that would have disguised the original beauty. The interior’s thick, fanciful moldings and red damask wallpaper remain, as well as the golden cherubs guarding the proscenium. The golden stage curtain, complete with tassels, framed vaudeville acts, live theater and movie premiers. The existence of this once proud theater teetered on the brink of ruin and beginning in 2007, legal wranglings kept the Ellen empty and ignored for several months.

As in other communities, Bozeman came together with donated work, money and materials to restore one of the most prized possessions of its historic past and present. In December 2008, the live audience sat in the richness again with the Ellen Theater reopening to an adoring community, with the Christmas Carol.

Given this valiant effort to preserve the past, maybe that is why America the Beautiful is the song chosen to represent the Ellen. To celebrate the theater’s 90th birthday, Weber gave a benefit concert.

Each community facing the task of preserving an iconic theater has Weber’s offer to do a performance to raise funds for further restoration. He hopes his reverence for these culturally significant buildings will bring greater visibility to the beauty of these theaters. “This was very liberating. It was heaven (recording in the old theaters). I would like to cast the net further to Texas, California, and the Midwest. But that’s a lot of travel with all the equipment.”

Rugged individuals settled the Western landscape, but did not want to be branded as unsophisticated. Every theater signified culture, richness and betterment for all. Even today, the same significance stands for every effort to save a historic theater in Rocky Mountain towns.

- Ellen Theater, Bozeman, Mont. the Ellen Theater, circa 1938, a Bozeman Main Street icon, has a healthy schedule of live performances, much to the delight of residents and continues renovation when time and money allows. Photo courtesy Pioneer Museum

No Comments