25 Sep The Exploits of John Colter

John Colter [c. 1775–1812] is among Montana’s most legendary mountain men. His iconic status is predicated on extraordinary feats of fortitude that occurred between the summer of 1806 and the spring of 1810, marking the beginning and end of his career as a trapper in the Rocky Mountains. Viewed collectively, those deeds constitute nothing less than an American odyssey, one often retold around the campfires of other mountain men and providing grist for numerous literary, biographical, and cinematic narratives.

Colter’s story began in Stuart’s Draft, near present-day Staunton, Virginia, where he was born between 1770 and 1775. Available evidence suggests that Colter first entered the written record on October 15, 1803, when he enlisted as a private in the U. S. Army’s First Regiment at Maysville, Kentucky. Part of the initial group of expeditionary members recruited by William Clark, Colter was one of the “Nine Young Men from Kentucky,” who formed the nucleus of the Corps of Discovery.

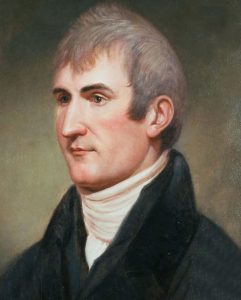

Meriwether Lewis portrait by Charles Willson Peale, April 1807. Lewis is best known for his service as co-leader of the Corps of Discovery. Indeed, he was specifically selected for that purpose by President Thomas Jefferson, who envisioned the expedition’s fundamental mission as early as 1793.

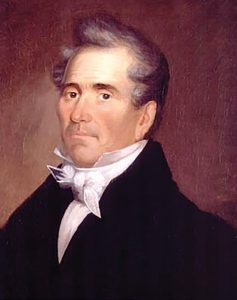

William Clark portrait by Charles Willson Peale, 1810. After completing his tenure as co-leader of the Corps of Discovery, Clark accepted President Jefferson’s invitation to serve as the principal Indian agent for tribes west of the Mississippi River. He went on to serve as governor of the Missouri Territory and later assumed the position and title of Superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis.

From the outset of their epic journey on May 14, 1804, until mid-August 1806, Colter served with distinction, most commonly as a hunter and guide. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s revelation that the headwaters of the Missouri were “richer in beaver and otter than any country on earth” attracted the first generation of mountain men, including Colter, to trapping grounds in Montana, particularly those in the Three Forks area.

Joseph Dickson and Forrest Hancock, trappers from Illinois, met Clark’s party on August 11, 1806, near Mandan (Numakiki) villages in North Dakota. Four days later, they invited Colter to join them on a trapping expedition up the Yellowstone River. Colter immediately requested a discharge from military service, which Lewis and Clark granted the following day. The explorers then provided him with essential supplies, like gunpowder and lead, that would be useful on his trip.

The partnership of Hancock, Dickson, and Colter was short-lived. Nevertheless, their departure on August 17, 1806, marked the first known trapping operation conducted on the Upper Missouri in the immediate aftermath of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Little to no documentary evidence survives about their whereabouts and activities during the winter of 1806–1807. However, pioneering fur-trade historian Hiram Chittenden speculates, based on subsequent events, that Colter wintered somewhere in the Yellowstone valley. By the spring of 1807, these three men went their separate ways, and Colter headed down the Missouri River once again.

Near the mouth of the Platte River, Colter encountered a large expeditionary force that was headed up the Missouri. Led by Manuel Lisa, a St. Louis-based fur trader with extensive operational experience on the Lower Missouri, the party included several Corps of Discovery veterans, most notably George Drouillard and John Potts. Their presence prompted Colter to reverse course and join their ranks.

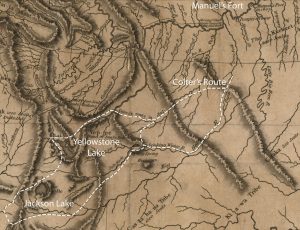

Researchers have exhaustively mined this portion of Clark’s 1814 map to reconstruct the route that Colter followed on his groundbreaking trek during the winter of 1807–1808. This cartographic representation reflects conversations between the two men, which occurred after Colter’s return to St. Louis in May 1810. For reasons that are unknown, Clark did not properly identify Colter’s starting point as Manuel’s Fort, which was located near the confluence of the Bighorn and Yellowstone rivers (see the extreme upper right corner of this image). | LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, GEOGRAPHY AND MAP DIVISION, WASHINGTON, D.C.

Lisa’s men reached the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn rivers in October 1807. On the Bighorn’s west bank, some 25 miles east of Billings, they immediately began construction of Fort Raymond, also known as Manuel’s Fort. Soon thereafter, Lisa dispatched four couriers in different directions to establish contact with Indigenous trading partners.

Serving in this capacity, Colter embarked on a journey that covered perhaps 1,000 miles, much of which was conducted alone, on foot, and in the dead of winter. Henry Brackenridge’s synopsis of Colter’s route, which first appeared in Views of Louisiana (1814), provides the closest facsimile to a primary-source account. “With a pack of thirty pounds weight, his gun and some ammunition,” Brackenridge states that Colter traveled more than “five hundred miles to the Crow nation, gave them information, and proceeded from thence to several other tribes,” before returning to Fort Raymond, “entirely alone and without assistance, several hundred miles.”

Considering the scarcity of documentary evidence available on this topic, Clark’s 1814 map provides critical insights concerning Colter’s route. Published in the Biddle edition (1814) of the Lewis and Clark journals, this map is a composite sketch, based originally on Clark’s personal observations and fieldnotes. Thereafter, he successively incorporated data from other sources, including Drouillard’s 1808 map.

After returning to St. Louis in May 1810, Colter visited Clark and provided a thorough update on events that transpired after his departure from the Corps of Discovery. The best-preserved legacy of those conversations is Clark’s depiction of numerous topographic features and landmarks that only Colter could have then identified, as well as the dashed line that Clark labeled on his map as “Colter’s Route.” Despite painstakingly meticulous research and analysis by historians, it remains impossible to definitively reconstruct the course our protagonist followed.

Gerry Metz | John Colter Exploring Yellowstone | OIL ON CANVAS | 30 X 40 INCHES | Colter is widely regarded as the first white man to explore the greater Yellowstone region. On Clark’s 1814 map, lakes Biddle and Eustis correspond with Jackson and Yellowstone lakes. A hydrothermal area along the Yellowstone River near Tower Junction corresponds similarly to Hot Spring Brimstone. Colter’s Hell, a concentration of fumaroles and hot springs near the Stinking Water River (North Fork of the Shoshone), constitutes a direct, historical link to our protagonist.

Nevertheless, scholars generally concur that Colter was, at minimum, the first white man to traverse the Wind River Range, the first to enter Jackson Hole and cross the Tetons, and the first to witness the geothermal features of Yellowstone National Park. Given the conditions under which it was performed and the significance of his geographical discoveries, Chittenden concludes that Colter’s long walk should be ranked among the “most celebrated performances in the [annals] of American exploration.”

The year 1808 was, as biographer Burton Harris observes, “the most eventful year of [Colter’s] life.” Three harrowing encounters with Blackfeet (Niitsítapi) and/or Gros Ventre (A’aninin) warriors occurred during the months that immediately followed Colter’s return to Fort Raymond. John Bradbury, an English botanist who met Colter in St. Louis in 1810, and Thomas James, who accompanied Colter on a trapping expedition to the Three Forks area in 1809, recorded primary-source accounts of these events.

Encouraged by the civility of initial contact with the Blackfeet, Manuel Lisa dispatched Colter to Three Forks during the summer of 1808 with the hope of establishing trade relations. Unfortunately, hostilities erupted between a massive Blackfeet war party and a Crow–Flathead contingent near the East Fork of the Gallatin River, only one day’s march from Three Forks. According to James, Colter was then leading the Flatheads (Sélis) back to Fort Raymond. Caught between implacable foes, Colter distinguished himself on the battlefield. Forced by a serious leg wound to fight from a seated position, he wielded his rifle with deadly efficiency until his Flathead hosts and their Crow (Apsáalooke) allies repulsed the Blackfoot offensive.

When news of this engagement spread among Niitsítapi bands, they apparently attributed disproportionate importance to Colter’s personal involvement. According to Harris, they ignored the obvious fact that Colter “had no choice,” under the circumstances, “but to fight for his own life.” Instead, they erroneously interpreted Colter’s actions as proof of an overarching alliance between Americans and the Apsáalooke. In any event, a report that Major Thomas Biddle submitted on October 29, 1819, to Colonel Henry Atkinson conclusively and retrospectively demonstrates that Colter’s participation in the Three Forks fight was the pivot point that triggered Blackfoot military opposition to incursions by American trappers.

Manuel Lisa portrait, artist unknown. Among those who sought to establish a foothold in the Upper Missouri fur trade following the revelations of Lewis and Clark, Lisa launched the most ambitious enterprise. His decisions to build a base of operations in the heart of Apsáalooke country and, later, to erect Fort Henry at Three Forks placed him in direct opposition to the interests of the Niitsítapi (Blackfeet) and A’aninin (Gros Ventre). These allied tribes responded by persistently attacking Lisa’s trapping parties until Fort Raymond was abandoned in 1811.

This change in diplomatic and military posture became evident during Colter’s next encounter with the Niitsítapi, which occurred in the fall of 1808 and culminated in the incident now immortalized as “Colter’s Run.” John Potts, a fellow veteran of the Corps of Discovery, partnered with Colter in trapping operations along the Jefferson River, where a large war party confronted them. Potts and one warrior were killed in the initial exchange of hostilities. Enraged by the death of their tribesman, other members of the Blackfoot party summarily dismembered Potts’ corpse. “The entrails, heart, lungs, &., they threw into Colter’s face,” according to James.

Stripped naked, unarmed, and hopelessly outnumbered, Colter was given the opportunity to run for his life. By the time he reached the halfway point of his 5-mile sprint, Colter had significantly outdistanced all but one of his would-be assassins. Alarmed by the sound of approaching footsteps, Colter looked over his shoulder and, according to Bradbury, discovered that his adversary had closed to within 20 yards. Colter immediately stopped and turned around. Startled by the suddenness of his actions and, perhaps, the appearance of Colter’s torso, which was heavily streaked with blood from an exertion-induced nosebleed, his pursuer stumbled. In the ensuing struggle, Colter seized the broken shaft of that warrior’s lance and fatally impaled him with its blade.

With renewed energy, Colter reached the Madison River and found refuge in a beaver lodge or logjam of driftwood, depending on the source consulted. Hours later, as silence finally settled over the area, it became evident that the main body of Niitsítapi warriors had abandoned the chase. Colter made his escape and eventually followed the plains bordering the Yellowstone back to Fort Raymond, a journey that James describes as covering “about three hundred miles [in] eleven days.”

Exhaustion, near starvation, and exposure to the elements tested Colter to his core. Doctor William H. Thomas, who published two of the earliest articles on Colter’s Run in 1809 and 1810, emphasizes that Colter did not even have “mowkasons to protect him from the prickly pear,” which were common along the route that he traversed. Therefore, excruciating pain must also have been Colter’s constant companion. One can easily understand why this gripping saga struck such a deep chord among Colter’s peers and subsequent readers. Indeed, biographer David Weston Marshall states that, by 1830, the “story of Colter’s Run had been published several times and had already emerged as a western American classic.”

Trappers affiliated with Lisa’s Missouri Fur Company continued to periodically conduct forays into Blackfoot territory until 1811, when Fort Raymond was abandoned. During this period, close scrapes relentlessly plagued Colter, and several of his comrades-in-arms, including Drouillard, were killed in skirmishes with Niitsítapi and/or A’aninin warriors.

Missouri Headwaters State Park remains a notable confluence where

the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin rivers meet. Within the context of the early fur trade era, it is virtually impossible to exaggerate the importance of the area. After Lewis and Clark reported that the headwaters of the Missouri were “richer in beaver and otter than any country on earth,” Three Forks became the ground-zero target of trapping operations on the Upper Missouri and the focal point of Colter’s most legendary experiences, including the hostile encounter with Blackfeet warriors that is now immortalized as Colter’s Run. | ADOBE STOCK/ L AMEEKS

James informs us that Colter reached his personal breaking point by April of 1810. He strode into the fort and solemnly vowed, “If God will only forgive me this time and let me off, I will leave the country day after tomorrow — and be d—d if I ever come into it again.” Colter wasted no time in fulfilling that promise. According to Bradbury, he traveled by canoe “from the headwaters of the Missouri [to St. Louis], a distance of three thousand miles, [in] thirty days.”

In the final analysis, efforts to precisely define Colter’s legacy are extremely challenging. Primary-source documentation is paper-thin for events chronicled in this saga. That shroud of mystery provides the perfect milieu for mythologization, as evidenced by the rapid proliferation and popularity of articles pertaining to Colter’s Run. The true measure of his exploits, according to Burton Harris, is the fact that, in seven years, Colter’s “solitary journeys and spectacular escapes [so] impressed the men who trapped and battled Indians with him [that his deeds became] legendary while he was still in the mountains.” Those sentiments were echoed much later by the fictional character Qualen, in Jeremiah Johnson, who remarked, in awe, that, “Some say you’re dead on account of this. Some say you never will be… on account of this.”

Douglas A. Schmittou is a freelance writer in Billings, Montana. His research focuses on travel in the Northern Rockies; evidence-based wellness protocols; and 19th century Plains Indian art, material culture, and ethnohistory. His work has appeared in Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Plains Anthropologist, and American Indian Quarterly.

No Comments