16 Oct The Birthplace of Public Lands: Rivals John Muir & Gifford Pinchot Collaborate at Lake McDonald

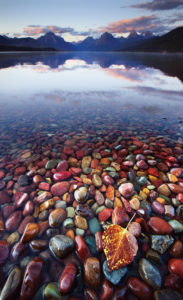

AT LAKE McDONALD, IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK IN JULY 2018, my moment came late in the day, after the trailhead parking lots had emptied, after the swimmers had docked their giant pink dragon floatie, after the families had retreated to campgrounds to roast marshmallows, after the sun had set and the pinks and oranges had reluctantly departed from the laketop and the alpenglow had started to fade. The mountain peaks emerged bigger, bolder, and darker, and I felt myself transported back 122 years to the campfire where John Muir and Gifford Pinchot talked joyously beyond the last of the twilight.

Photography by Jason Savage

- Avalanche Creek

- Lake McDonald

- McDonald Creek

Amid this idyllic setting, Muir and Pinchot debated public land policy with other members of the National Forest Commission.

THE BIRTHPLACE OF PUBLIC LANDS

Gifford Pinchot, then just 30 years old, had spent the previous month wandering the nearby wilderness and was delighted to discover that Muir had joined the commission for this trip.

I was on a quest to understand that interaction, because Muir, the famous naturalist, and Pinchot, founder of the U.S. Forest Service, are often seen as enemies. They once clashed over a proposed dam in the remote Hetch Hetchy Valley of Yosemite National Park. The romantic Muir, Yosemite’s most ardent defender, opposed this defilement of a national park; the pragmatic Pinchot testified that a half-million San Franciscans could gain drinking water from the reservoir.

But here in Glacier, a decade previous, they’d shared a bond. My quest to understand their relationship had begun 14 months earlier, when I came to Glacier to first research this encounter. On that visit, I was working in the park’s library and archives, trying to pin down some facts about the events of 1896 for a book I wanted to write about the two men.

However, I’d also managed to snag a lakeside campsite at Sprague Creek, thanks to the relatively small springtime crowds. I gazed out at the lake at sunset, taking notes on how to describe unending forests spilling from bare pointed peaks all the way down to impossibly clear waters. If I was going to write about Muir, I hoped to describe the setting in a way he might find satisfactory.

And I found that the lake spoke to me with more than descriptive phrasings. Reimagining the Muir–Pinchot encounter caused me to question the conventional story of their rivalry. Hetch Hetchy has come to serve as shorthand for a philosophical divide: Muir personifies preservation, the idea that humans should leave nature alone so as to benefit from its holistic wonder; Pinchot personifies conservation, the idea that we should use natural resources sustainably to serve the “greatest good for the greatest number in the long run.” The way I’d learned environmental history, the clash between these worthy ambitions traced back to these two men, and stymied the movement through the 20th century.

But how could they have clashed in this idyllic spot? They shared so much. Indeed, my research showed that they both used the word “delight” to describe their Lake McDonald experiences. Camped at the lakeshore, confirming its beauty, I was inspired to dig deeper. What if their time here was not only delightful but also important?

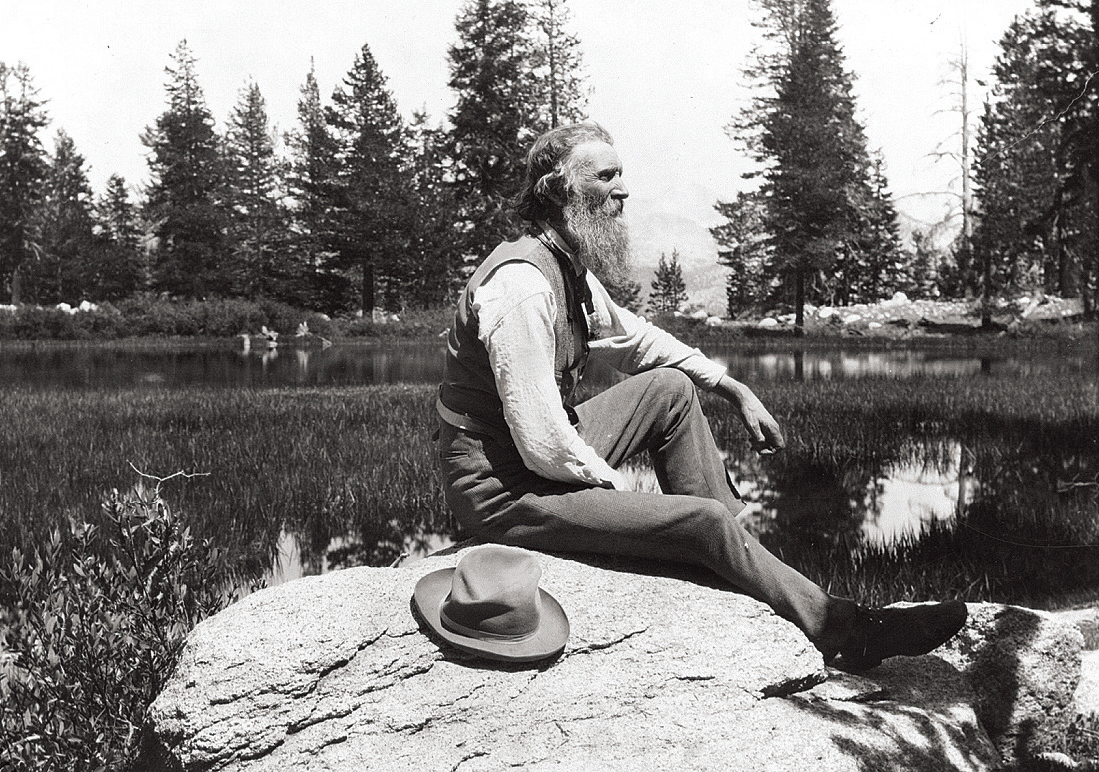

BEFORE SUNRISE ON JULY 16, 1896, Muir and Pinchot encountered each other by surprise at the train station in Belton (now West Glacier). The 58-year-old Muir, with his typically unkempt beard and odd gait, arrived with the National Forest Commission, a blue-ribbon panel charged with developing a policy for rational management of American forestlands. Muir, the anti-establishment individualist, wasn’t an official commission member, but he had decided at the last minute to travel across the country with them.

- McDonald Falls

- Trail of the Cedars

- Avalanche Lake

- McDonald Creek

- Lake McDonald

Also waiting for the train was the 30-year-old Pinchot, 6 feet 2 inches tall and gaunt with a stylishly brushy mustache. He invited the group for coffee at his camp along the Middle Fork of the Flathead River. He’d already been in Montana for a month, hunting and hiking. Although he was the commission’s official secretary, he’d traveled so far off the grid that nobody knew if he’d received the telegrams planning this rendezvous.

Thus each man was surprised to see the other. Also delighted. After previously meeting three years before, they had become vigorous pen pals. As the commission took stagecoaches from Belton to Apgar and rode a steamboat the length of Lake McDonald, Muir and Pinchot talked incessantly. They shared a love for outdoor adventure, the youth to pursue it, and the intellect to put it in context.

The rest of the commission — older, esteemed scientists — stayed in a crude hotel at the site of today’s Lake McDonald Lodge. But Pinchot and his guide set up camp nearby. Muir joined them. Muir even tried fly fishing with the expert Pinchot. While the rest of the commissioners ate indoors, Pinchot and Muir delighted in their fresh-caught, campfire-charred dinner. Then they talked long into the evening.

They likely talked about this gorgeous setting, and the need to treat it differently than the rest of the public domain. Glacier was not yet a national park — that protected status would not come until 1910 — so this land was simply waiting to be given away to homesteaders.

In other words, like much of the land in the West at the time, it was “public” land only in that it was not yet privatized. Although we often speak of public lands as an American birthright, the idea that the government would permanently own some landscapes started emerging only in 1872 — and was then expressed only at remote, little-visited, military-run reserves, such as Yellowstone.

However, the private land ownership model was beset by market failures, including a “timber famine” that experts believed might arrive within a decade. The commission was assembled to address this pending crisis, and to identify a set of landscapes to be governed by a new policy. Muir and Pinchot could easily agree that the Lake McDonald area should gain such protections — indeed Muir called Lake McDonald “one of finest [lakes I] ever saw.” Evidence suggests that they also had deeper conversations, reflecting their rival attitudes toward nature.

Often called “America’s first forester,” Pinchot championed sustainability. He saw how trees supported so many sectors of the economy, and he wanted to make sure they’d be available in coming decades. Likewise, he saw how mountain watersheds were essential to downstream agriculture, and he wanted to protect forests as natural reservoirs. Pinchot believed that recent advances in science and management could allow forests to become more efficient, less wasteful, and thus capable of fulfilling more of these diverse societal needs.

And it’s funny how, compared to his earlier work, the essays and interviews that Muir published from 1896 to 1898 very much reflected these “multiple use, sustained yield” values — as if he’d learned new perspectives from listening to Pinchot.

By contrast, Muir’s big issue had always been spiritual fulfillment. He believed that forests and mountains were places to experience wonder and see God. Certainly that’s what moved him about the extraordinary scenery at Lake McDonald, which he hoped could be kept intact.

And it’s funny how, when Pinchot wrote his autobiography 40 years later, he expressed such effusive, specific, unmitigated admiration for the way Muir prodded him to think about these deeper issues — as if the master had opened him up to new perspectives.

At Lake McDonald, Muir and Pinchot weren’t preservation and conservation locked in inevitable battle. They were two magnificent individuals whose diversity bloomed in a beautiful place.

Today’s Lake McDonald Lodge is near the spot where Muir and Pinchot camped.

FOURTEEN MONTHS AFTER MY first lakeside insight, I returned to Lake McDonald with a bigger question. I had since learned not only about Muir and Pinchot, but also about the results of the National Forest Commission’s work. It’s commonly seen as a failure: When President Grover Cleveland implemented its recommendations in February 1897, intense opposition nearly led to a government shutdown.

But as Pinchot later wrote, the controversy caused the issues of forestry and public lands to be “widely, simultaneously, and here and there intelligently discussed by the press and the people of the country.” Muir’s essays and interviews provided the spur and framework for those discussions. Muir not only used his brilliant rhetoric to spread Pinchot’s forestry gospel, but he also implied that, thanks to Pinchot’s administrative talents, people could trust the government to manage these lands wisely.

In other words, the commission’s failure led to a partnership between Muir’s verbal gifts and Pinchot’s managerial ones. This collaboration has often been hard to appreciate, because its results didn’t establish organizations. Instead, it changed attitudes. The 1897 to 1898 compromises forged to avoid the government shutdown, and established principles of government forestry and public lands that the public embraced — and still embraces today.

Returning to Lake McDonald in 2018, I tested my theory that the Muir-Pinchot alliance helped create our public lands legacy. On this visit, I spent much of my time on the shoreline below Lake McDonald Lodge. Although it was landscaped into promenades and boat docks, the post-sunset emergence of mountain glory felt unchanged from 1896. It was, as Muir wrote in his diary, “lovely, ethereal.” At the highest peaks, the alpenglow faded, from bottom to top, until my magical moment when just a single beacon remained.

I was shocked at how few tourists witnessed it. The lakeshore at dusk provides one of Glacier’s most emotionally resonant, spiritually confirming moments. It felt especially easy to transport myself to that long-ago moment when Muir and Pinchot made the first steps toward a national public lands policy — when they articulated a shared belief that landscapes like these could be productively managed, through democratic processes, for the benefit of all.

No Comments