24 Aug Artist of the West: The Art of the Sporting Life

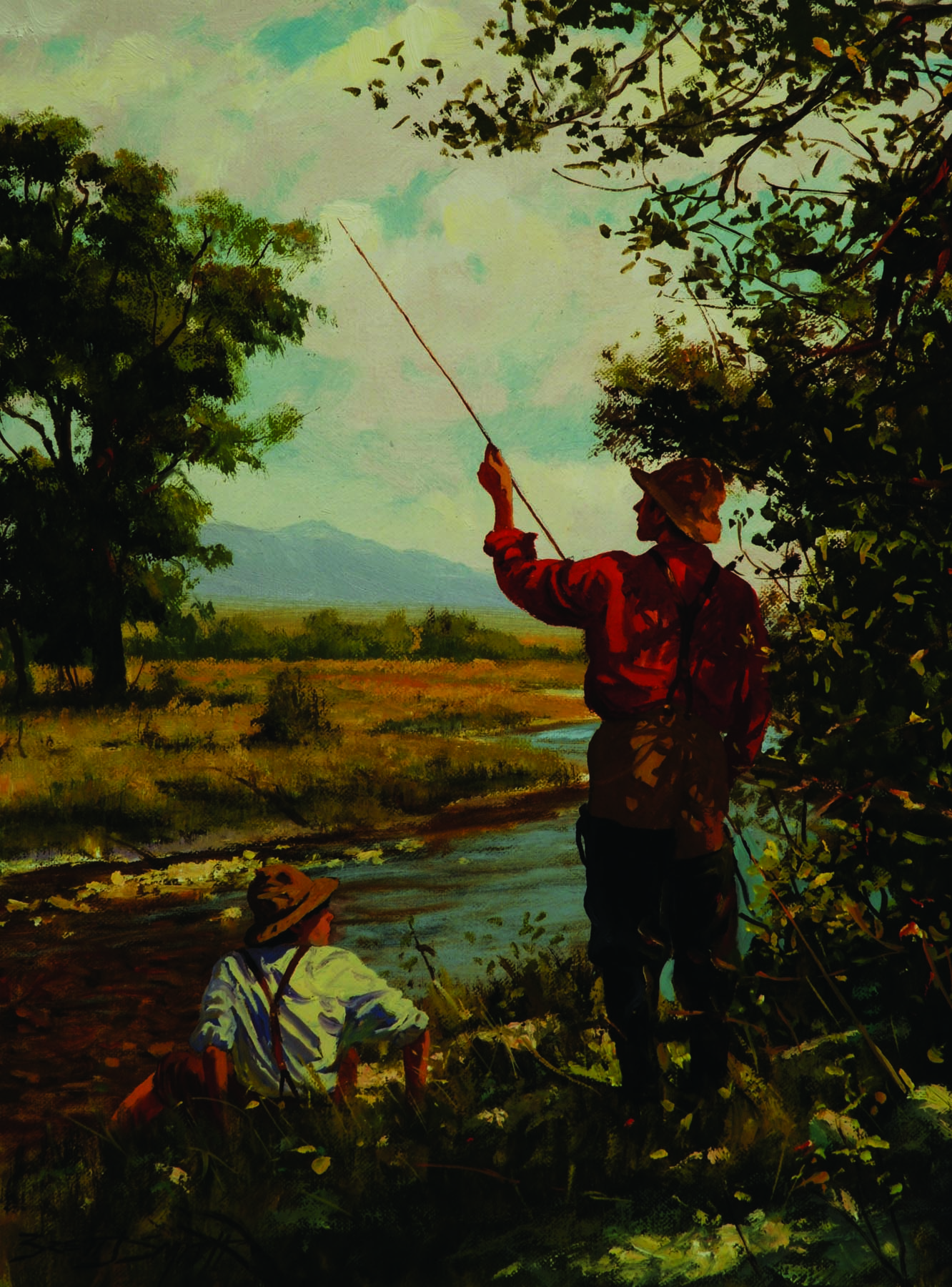

IT’S EARLY. THE SUN IS BARELY over the horizon. The wind, not yet awake, rests in the nearby willows. An angler stands calf-high in the sleepy current, casting his line long, arcing it into a busy riffle on the edge of a mirror-still hole, with the promise of a good story to put in the creel, if not the trout itself.

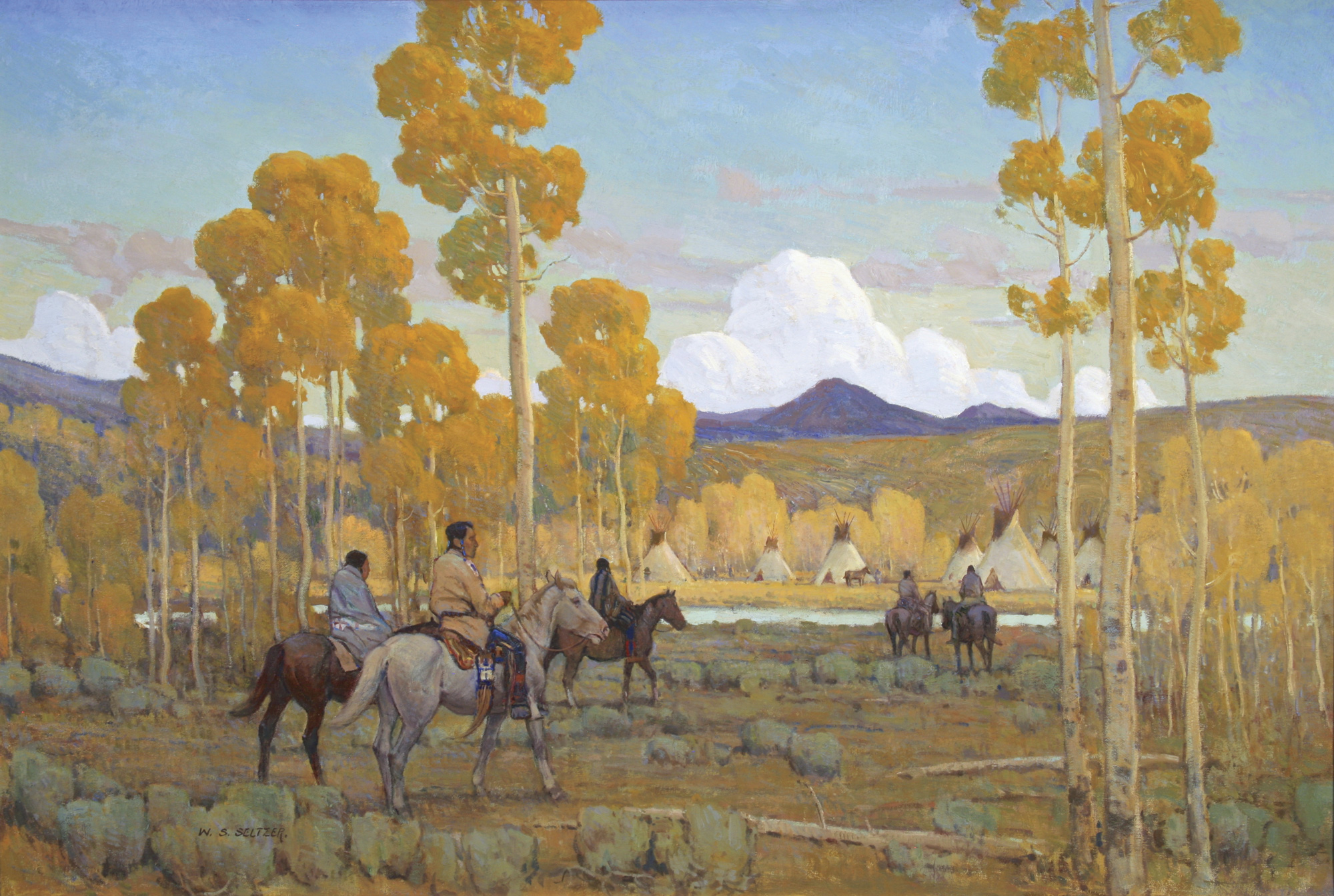

This is the narrative playing out in Brett James Smith’s Fishing Spring Creek, one of his recent pastorally perfect oil paintings. It may not be you, but it could be. And that is the allure of Smith’s work.

Authenticity plays a major role in Smith’s paintings as well as in his life. By working to create the truest paintings, Smith transports us to his secret fishing holes.

Taking the advice that illustrator N.C. Wyeth took from his mentor Howard Pyle, Smith jumps into his paintings “to know the place.” Careful to include as much detail as is necessary to convey the experience of fly fishing, Smith’s scenes feel true, if not contemporary. He prefers to depict an agelessness, capturing the nostalgia of the sporting life.

“What is important in these outdoor paintings is mood, a feeling of how things were and still can be,” Smith says. “Most of the paintings I do try to elicit some kind of mood. That’s what is so important.”

Smith doesn’t feel comfortable recreating a photograph, something he would never even try to do.

“I need to think about what’s driving me when I sit down to paint,” he says. “In most cases I create paintings once I envision the final result. When that happens it’s usually successful.”

Growing up around the bayous outside of New Orleans, Smith fished as much as he could — in the salt water of the Gulf of Mexico and in the marshes. Once he got older he discovered fly fishing and Montana.

“When you love to do something it’s only natural you want to document it,” he says. “Most people document it with an iPhone but I’m able to document it with paint. Even if I was painting portraits I’d still make fly-fishing paintings, just for myself.”

On a pack trip out of Missoula, heading into the Bob Marshall Wilderness, Smith found Noxon, located right on the Bull River. At that moment, he knew that’s where he wanted to spend his summers.

“I can look out from my studio and see the pools and see when the fish are eating,” Smith says. “Which is pretty much all day, but they get hard to catch, there’s not enough riffle, pretty flat water. It’s a great little river and there’s rarely anyone on it.”

Smith paints in both transparent watercolor and oil paints, depending on the subject and what he’s after in the painting. Oils translate better for large complex scenes. Watercolors are more spontaneous.

“I get lots of calls for oils but I enjoy doing watercolors more because they still challenge me,” Smith says. “You have to be intuitive. Free to let the painting do what it needs to do and take you where it wants to go.”

Smith is always fighting with the idea that only oil paintings are fine art and watercolors are more of a quick field study and not as permanent as oils. But really good watercolors, watercolor work like Smith’s, are hard to find. The amount of detail Smith can get into a watercolor is astounding. He has somehow found the secret to fine lines and color depth that is usually associated with oil painting.

“I want to do the same things with watercolors as I do with oils, but there are different ways to accomplish it,” he says.

The biggest difference is that watercolor paintings are done in one sitting.

“It all comes together in the last 15 to 20 percent of the painting,” Smith says. “The rest of the time it looks a mess and I don’t think I’ll ever get it to the point where I’ve envisioned it. And that can scare a lot of people off. It’s a matter of understanding that it’s part of the process. It just takes experience to realize that.”

For Smith that chaotic first 80 percent of the painting is the fun part.

“A lot of people think those paintings are spontaneous but they’re not,” he says. “They’re made to look that way, to look like they’ve been painted in minutes rather than hours. To make them look like that takes experience. That speed I create in the process — that spontaneity that comes across — is what people are attracted to.”

Although Smith does admit that he is a fast painter.

“When people ask me how long it takes to create an image I always tell them it takes 30 years,” he says.

And that may be true. Smith began his career as an illustrator and worked at many of the top-tier sporting magazines, including Gray’s Sporting Journal, where he is still a frequent contributor.

“I’ve known Brett a long time, over 20 years,” Wayne Knight, Gray’s Sporting Journal art director, says. “I could see his work growing and his style progressing. He uses beautiful colors, very realistic. It makes you feel like you could be doing that. It’s also so much better than a photo because he goes in depth with his work. If you can’t be standing in a stream fly fishing, you can imagine yourself doing it.”

Knight says Smith has been in nearly every issue because of the way the artist can take a reader into the story.

“We don’t assign illustrations at Gray’s,” Knight says. “I read the stories and then I pick the art. More often than not I’ll think of one of Brett’s paintings. You can tell that he fly fishes because everything he paints looks visually correct and a savvy art collector will notice that. Brett’s stuff is always just right on.”

Working as an illustrator allowed Smith to cut his teeth painting fishing and hunting scenes.

“I used to do a lot of duck hunter paintings,” Smith says. “When I did those paintings I never put the dogs in the scene, because people with dogs will love the painting either way, but people without dogs won’t relate to it.”

With a similar type of instinct as to what collectors are looking for, Smith’s fly-fishing paintings stay away from the high-tech gear.

“I started painting guys in the 20th century with creels,” he says. “I never did like to paint guys in blaze orange with waders and that sort of thing.”

By staying away from modern clothing, Smith is able to get to the heart of fly fishing, the meaning of what it feels like to stand in the river, the gentle current rippling around you, waiting for the tug on your line and trying to think like a trout.

“People who don’t use a creel or wear hip waders still appreciate doing it the simple way and that’s why it won’t ever lose its luster,” Smith says. “It’s something they can relate to, even though the packaging has changed. It doesn’t turn people off. You look at the history of sporting art, the turn of the century of fly fishing: Most of those paintings were done more for the pleasure of the painter rather than something he was selling.”

And there’s something to be said for romanticizing the good times on a quiet stream.

“I don’t usually paint the bad days, the days when it rains,” Smith says. “You don’t want to remember those days.”

Curtis Tierney of Curtis Tierney Fine Art represents Smith’s work and admires the way Smith can translate his knowledge of fishing into a scene, describing his style as expressive representational art.

“He’s an incredibly skilled fly fisherman and that shows in his paintings,” Tierney says. “Look at the casting positions of his subjects, their positioning in approaching the best water is all correct. Brett lives the life he paints and people will know that level of expertise and can appreciate it.”

As an art dealer, Tierney feels that Smith’s watercolors are some of the best buys on the market today.

“They sell for a fraction of an oil and in my opinion his watercolors are one of his strongest mediums,” Tierney says. “He’s painting in oil at the top of the field, so to say his watercolors are potentially better is a grand but true statement. They are exceptional and can be compared to the best watercolorists of the day.”

And still it comes down to what he knows and loves that makes Smith the painter he is.

“The part of Brett’s DNA as a painter is his familiarity and expertise in field sports and fly fishing,” Tierney says. “If he wasn’t so dedicated to his painting you’d find him on the river every day.”

- “A Good One” | Oil on Linen | 16 x 20 inches

No Comments