15 Jul Textile Twist

AT FIRST GLANCE, MAGGY ROZYCKI HILTNER’S textile pieces are lush, bright and nostalgic: Dick and Jane-like figures playing in a flower-filled garden, animals and children romping happily in a meadow. But then you take a closer look. In Pastoral Scene, a giant chipmunk holds a little boy by the neck and a girl by the ponytail while menacing-eyed deer look on. In The Monsanto Twins Try a Little Genetic Engineering, two cute, ostensibly innocent boys wave “gene guns” at one another.

Using a unique blend of found textiles, appliqué, and detailed embroidery, the 36-year-old fiber artist makes playful, poignant remarks about childhood, gender, sex and nature. Her humor is clever, sometimes biting.

“If someone says ‘that’s pretty’ about one of my pieces, they’re probably not really paying attention,” Hiltner says. “With my work, I’m recalling the universal joys and the darker side of childhood, stories from my past or stories I’ve heard from others, the anxiety I feel about interpersonal relationships or nature. I like taking a comfortable and familiar medium — fabric and stitching — and using it to convey these more prickly themes.”

Hiltner was introduced to sewing as a child, but she didn’t consider it “art” until well after she completed a degree in sculpture at Syracuse University, when she found herself drawn back to textiles. From the beginning, she used found pieces — tea towels, doilies and other household embroidery — she discovered in thrift shops and antiques stores. At first, she stitched directly onto these salvaged pieces, but eventually she gave herself permission to cut them up, combine them on a new backing and then embellish them with her own embroidery — placing the angry-looking eyebrows on the deer in Pastoral Scene, for example. And from these montages of antique textiles and Maggy’s own stitching come stories.

Hiltner’s pieces range from one-scene vignettes to large-scale tableaus that give a sense of narrative progression. When I arrive at her studio outside of Red Lodge, Mont., she is sorting through her collection of found textiles, separated into storage bins by color, preparing to work on a 12- by 4-foot piece for a juried exhibition at the Bellevue Arts Museum in Bellevue, Washington. “I want this piece to center on anxieties around nature and sexuality. The question with anything I do is, how do you get as much information as possible into a small space? With the larger pieces, it’s often, how do you fit the entire universe in a panel?”

Hiltner shows me a stack of books she has been browsing to glean ideas and inspiration. Among them are Sir Kenneth Clark’s Animals and Men, which contains more than 200 examples of the influence of animals on Western art, and a stunning collection of works by the 15th century Dutch painter, Hieronymus Bosch, the creator of the luminous triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights. “Bosch is a real influence for me. I notice the strange and absurd details in his work. I enjoy the long history of narratives and allegories in art. I’m trying to explore these elements in my own medium.”

In 1995, Hiltner moved to Red Lodge with her husband, David, and their young daughter to establish the Red Lodge Clay Center, which features a residency program, workshops, community classes and a gallery of work by nationally-known artists. Before then, the couple lived in Powell, Wyoming, and in Wichita, Kansas, where David headed the Ceramics Department at Wichita State University.

In Powell, Hiltner found the textiles of the homesteaders: lace petticoats, white kid gloves and doilies. The resulting work was mostly white-on-white and fairly abstract in its ideas and imagery. In Kansas, the pieces she discovered were dominated by colorful Midwestern kitsch: dancing teapots, kittens in aprons and vibrant flowers and foliage. In Montana, she continues to hunt for brightly colored pieces to integrate into her work, but here the theme tends toward Western iconography: horses, cowboys and tack.

“I like to think I have anonymous assistants,” Hiltner says of the women who stitched the textiles she has collected over the years. “Part of my intention is to save women’s work. Women put thousands of hours into these pieces. My hope is to raise their work up, to validate it. To think your grandmother’s embroidery wound up in a museum, that’s okay.”

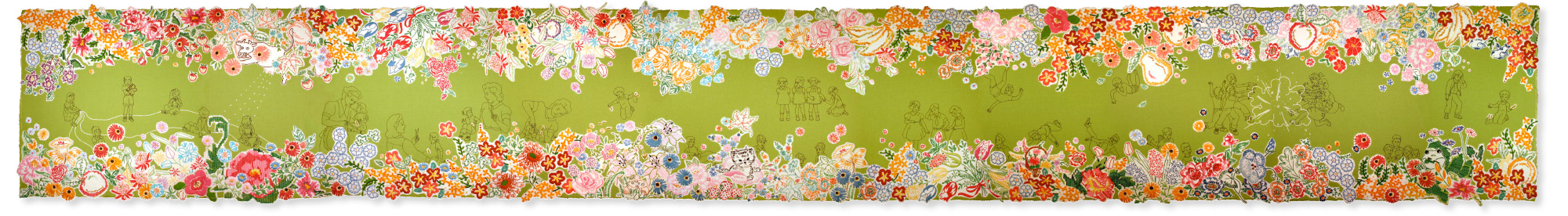

Hiltner’s work has garnered attention from critics and writers from The New York Times to National Public Radio, and has been included in a number of catalogs and books about textile arts. She has exhibited in New York, Los Angeles and many cities in between. Last summer, her piece Hothouse Flowers was included in an exhibition at the prestigious Textile Museum in Washington, D.C., which celebrated the symbolism of the color green, exploring themes such as sustainability, recycling, and the interconnectedness between humans and the natural world. Measuring 144 by 18 inches, Hothouse Flowers is a panorama of scenes of children playing, fighting and teasing against a background of vibrant green and surrounded by a gorgeous border of bright flowers and fruit.

“There’s a lot going on in Hothouse Flowers,” Hiltner says. “One of the themes is my question about the increasing pressure in our society for children to excel, achieve and mature. It’s about the parallel dangers of pushing growth in both children and nature — with bovine growth hormone, fertilizers and hothouse production, for example. That overgrown verdancy is threatening to me, untrue. It links to tarted up preteens and too-soon sexuality.”

Mary Lee Larison, owner of the Turman Larison Contemporary gallery in Helena, has great respect for Hiltner’s work. “I learned about Maggy a few years ago when I was curating pieces for an exhibit at the gallery we called The Mom Show, which featured work by women from around the country — all with kids under the age of 10 — who were still trying to make it as artists. When I saw her Web site, I was amazed by the humor, the craftsmanship and the scope of it. I wanted all of it for the show. Maggy’s pieces speak to me. I don’t consider myself someone who collects things from another era, yet I love the nostalgia. Her work is deeply connected to women, and then there’s the twist she adds: the humor, the askance view. She’s sardonic, not sarcastic. Maggy comes at what I consider to be a rather bland form of art — anyone could make this doily, this tea towel — and creates something entirely fresh and new. [She] clearly loves the material she uses and subject matter she creates.”

Indeed, for Hiltner, love is a necessary ingredient in the creative process. “Some of my pieces take months to finish. The challenge is, how do you keep the energy of love for that project alive? It’s kind of like the naïve intensity a child experiences working on a Mother’s Day project. You just can’t fake it.”

- “Hothouse Flowers” | 2005 | Hand-stitched Cotton and Found Textiles | 18″ x 144″

- Maggy Rozycki Hiltner

- “Color Sketch 4″ | 2011 | Hand-stitched Cotton and Found Textiles | 9″ x 9”

- “Pastoral Scene” | 2007 | Hand-stitched Cotton and Found Textiles | 16″ x 22.5″

- “Color Sketch 1″ | 2011 | Hand-stitched Cotton and Found Textiles | 9″ x 9”

- The tools of the trade.

- From left: “Surly Frog” | 2009 | 9 ” x 8″ • “Terrible Turtle” | 2008 | 9 ” x 8″ • “Sullin Bear” | 2008 | 9 ” x 8″

No Comments