30 Jan Swinging Streamers

Fishing streamer flies is a departure for me, as I suspect it is for most trout anglers. Though it’s a fascinating business, since the huge trout it may unleash echo in every cast and swing of the big, full fly, the genteel delights of dry-fly fishing or the productiveness (and modest odds of moving a big fish) offered by the artificial nymph generally win out.

Fishing streamer flies, those outsized patterns imitating or vaguely suggesting small fishes, was, in my boyhood, an uncomfortable and unyielding mystery. When do I fish them? Where? How? Though I tried them on occasion, they seldom caught trout.

Time, though, has had its effect: The trout of 3, 4, or more pounds I’ve caught on streamers over my decades of fishing have drawn me to using the patterns ever more frequently. And I fish them at least as often in Montana rivers as in any.

It’s possible my first Montana streamer trout came way back in my teens, perhaps on the Yellowstone River. I have some vague memory of that.

But I do know that, decades ago, when I was drifting Montana’s Bitterroot River with a guide friend in his rugged inflatable river raft late in the day, I tied on an imitation of a sculpin, a little iguana-headed fish that trout chase and eat in streams. We’d caught cutthroats and some rainbows on dry flies, but I began tossing my chunky fly at the shoreline, twitching it back, and soon felt a yank come through the line. The streamer grabber was a 17-inch brown, 18 perhaps? Notably bigger than any of the cutts of that day. No trophy, but a fine trout.

I’ve had plenty of other large to giant Montana steamer trout since.

Morris Minnow

What constitutes a giant trout is subjective — no number of inches or pounds has ever been decreed. Or could be. Or should be. Big is what’s big to you, and to the water you’re fishing: a 14-inch rainbow from a creek of 8-inchers is a wonder, a maker of shaky hands and shining eyes — yes, a giant.

If you’re a seasoned big-trout specialist, my “big” Montana streamer trout won’t impress. (Well, one Missouri River brown might: easily 24 inches.) While I love a big trout, I also love the long list of characteristics that average or even small trout can offer: their slash at a size-14 bristly Royal Wulff, bouncing on the sparkling wavelets of choppy currents; their soft rises to tiny hatching insects, Trico mayflies, midges, the smallest caddisflies, pocking smooth water with gentle sips; their sudden exciting pull on a swung wet fly.

So I’m no trophy chaser, at least not consistently, and only an occasional streamer man. But, by God, I’ve had some streamer adventures in Montana, fly fishing’s Sacred Land.

One September morning, when my wife, Carol, and I were up and unable to sleep before dawn, we drove to a boulder-set bank of the broad Upper Missouri River and, in the dusky light of an invisibly rising sun, saw no trout feeding at the water’s surface to make floating flies make sense. Considering conditions, streamers did make sense. We walked the dusty flat earth that backed the top of the boulders and climbed down among them to cast. Every sixth swing or so, our flies down only a foot in the current that churned along the jutting rocks, we felt a yank through the rod or saw the distinctive boil of a trout grabbing our streamer. Some fish we landed, some we lost, but by the time the sun touched the water we’d hooked, landed, and freed several browns and rainbows of 17 and 18 inches.

Zoo Cougar

The next day, and a few others, we made plans, went to bed early, and woke to the raspy ringing of our ancient wind-up alarm clock. Then, we were back at our boulder-stacked bank again, swinging streamers. Increasingly, the trout understood what our pre-dawn streamers really offered: a poke in the gums and a scoop of the net before getting sent back home. Enough innocents remained, however, that we always caught something.

Even today, it seems most fly fishers are as uncomfortable fishing streamers in trout streams as I was through all my young life, asking themselves, When? Where? How?

When, I’ve learned, is simply whenever streamers work, which can be about any time; especially, though, in the early morning and at sunset.

The where of fishing streamers is mostly about finding big trout. Not all trout streams hold big trout. And most of the structure in nearly all trout streams doesn’t suit truly big trout; you have to hunt down their lairs. Yes, average trout will take little streamers not much larger than average trout flies, and though that’s all respectable enough, streamers, by their history, by their common use, and by the very spirit in which anglers regard them, are big-fish flies.

Double Bunny

How to fish streamers? Well, here’s how I do it.

I nearly always fish streamers on sink-tip fly lines. I might toss a streamer upstream of a place where big trout might hold, allow it to drop and drift free for a bit, then let it swing across the current while perhaps giving it a jerking or jittery swim not far beneath the surface of the river. Or I might present it downstream, holding it against the current along some promising deep bank while twitching it to life. Or let it really go down with the sinking line, then swim it slowly across the rocky bottom of a pool or run.

The numbers may be small — four or five grabs and two or three fish landed in a day is a good streamer day on most rivers. But with those two fish you may tremble, feel weak, need to sit.

The streamer, like all flies, comes in a wilder range of colors and designs than it did when I took up fly fishing as a boy. Back then, we had “bucktail” flies, filled out with the long pliant hair from the tail of a male, or buck, deer, and there were “streamers,” which were also meant to be fish-like flies but with long, trailing feathers doing the work of the buck-tail hair of the former.

Clouser Minnow

Now, nearly all fish-imitating flies are collectively called streamers — squeezing most of the current designs into one of the two old categories would take a shoehorn and a lot of force and grease.

The Clouser Minnow, for example, the invention of Bob Clouser of Pennsylvania and the late Lefty Kreh of Maryland, is likely the most popular of all true streamers today. The Clouser’s back and belly are, in fact, made of buck-tail hair, but a traditional bucktail fly it is not — its nontraditional-to-the-absolute metal eyes flip its hook upside down in the water and, unlike the Edson Tigers (both the Dark and Light), the Black-Nose Dace, and other classic bucktails with bodies of plush chenille or gleaming silver or such, the Clouser has no body at all.

For the biggest of big trout, there are streamers like the Double Bunny, created by Scott Sanchez of Livingston, Montana, which includes two strips cut from rabbit hide, fur intact, cemented together so that gray fur suggests the back of a real fish and white fur the belly.

Those are two contemporary streamers you’re liable to see anglers working in trout streams, but when you go back in streamer-fly history, you find Montana contributing more than its share. For decades, the Muddler Minnow — with its puffed head of packed and shaped hair, body of gleaming gold tinsel, and oak-turkey wing and tail — was the first-call streamer across the U.S. (despite that it really fit neither the streamer nor bucktail categories of the time). It was invented in 1948 by Don Gapen, who owned a resort in Ontario, Canada and who seems to have used the fly only for his own fishing. Then, Dan Bailey, of the genuinely famous Dan Bailey’s Fly Shop in Livingston, Montana, promoted it and made it famous, too. In time, Bailey replaced the turkey wing with downy marabou to add motion, creating the Marabou Muddler.

The insanely popular Woolly Bugger, arguably a streamer (to many, it’s a nymph or leech imitation), has Montana roots as well. More recently, Kelly Galloup, owner of the Slide Inn (a fly-fishing shop and lodge just 200 feet from the Madison River), has come up with all sorts of interesting to odd trout-catching streamers, some of which are North American standards today. (Take a gander at his Zoo Cougar sometime, if you aren’t already fishing it.)

Muddler Minnow

On a Montana river big enough that one could cross it only at its widest, thinnest spots, once came an evening crowned beautifully by what a streamer-fly touched off. We faced a long, deep pool, whose sprinkled line of white foam ran from just below the fury at its head nearly to the wide lip of its tail. In the early evening of a fall fishing day, the trout should have risen to insects collected with the foam in the creasing of currents, but few did. So, Carol and I switched from dries to nymphs below strike indicators and drifted them out in that midstream crease. We caught some cutthroats, then browns — perfectly satisfying trout, all 10 to 15 inches long.

Almost at the head of the pool, where the water burst in violent white under the last light of sunset, I tossed out a Morris Minnow tied in brown-trout colors. A streamer furred by mirror-like fine Mylar ribbon; a final wild-card move of the day. After a few casts, the streamer stopped — hard — and I set. The big fish raced off. It was a classic fight: angry runs, line recovered between them, just a rocky stream bed and no water weeds or submerged timber for the trout to use, a clear cobbled bank for fish chasing. The big trout tired, coming, at last, to net. Actually, to hand — my large net was too small to contain the brute. I held that long slab of a yellow-flanked, red-and-brown-spotted brown trout up briefly for Carol to photograph, then cared for him as he recovered and, at last, swam tiredly away.

He was not my biggest Montana streamer trout. But he was as thrilling as any.

Woolly Bugger

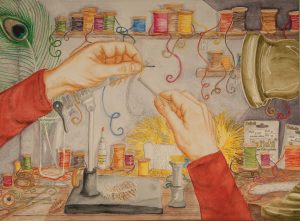

For more than three decades, Skip Morris has made his living by writing — 19 books to date — and speaking about fly fishing. His first book of essays is due out in late 2025 or early 2026. His wife, Carol Ann Morris, provides illustrations, paintings, and photographs for his articles and books.

Carol Ann Morris is a fly-fishing photographer, speaker, and artist/illustrator whose work appears often in books, articles, and essays written by her husband, fly-fishing author Skip Morris. Seventy-five of her drawings will appear in Skip’s next book, an essay collection; etsy.com/shop/carolamorrisflyfish.

No Comments