08 Jun Images of the West: Stephen Mather: A Champion for Glacier

When the National Park Service emerged as a new federal agency in the Interior Department 100 years ago on August 25, 1916, nobody in Montana took much notice. It did not make the front pages of the local newspapers — or even the back pages. It wouldn’t be until January 1917, just after the new Park Service director, Stephen Mather, paid his first visit to Glacier National Park, that The Columbian in Columbia Falls gave a nod to the new agency — right next to a much larger headline proclaiming that the annual state poultry exhibit would be held in nearby Kalispell.

In 1916, Glacier was not on the way to anywhere. Of all of the nation’s 14 widely scattered national parks, it was likely the most difficult to reach. The main line of the Great Northern Railway provided the only year-round access to the park’s east and west sides. There was a crude “tote” road from the Flathead Valley to Belton in West Glacier on the west side; on the east side, the railroad had cut out unimproved roads — nearly impassable in wet summer periods — that led to its newly-constructed hotels and chalets. Nonetheless, Mather set out by train from Chicago in September 1916 to conduct his first tour of the park.

That Mather made his way to Glacier at all in his first year as director of the Park Service was testament to his personal interest. After his visit, he filed a report with his superiors and sent a copy to The Columbian proclaiming his desire to push ahead with new roads, trails, telephone systems, a bridge over the Middle Fork River, and expanded staff. Regarding the deplorable conditions at the Fish Creek headquarters, Mather said, “The headquarters of the park are now hidden in the woods on the southwest shore of Lake McDonald and are wholly unknown to nine-tenths of the park visitors.” To back up his support for Glacier, he scratched out a personal check for $8,000 to purchase 160 acres of private land just inside the park’s boundary and across the river from the rail depot at Belton as an “administrative site” for the new headquarters. He then donated the land back to the park. Still in the mood to cut deals, he met with John E. Lewis, owner of the recently constructed Lewis Hotel on Lake McDonald, to purchase and preserve a vast stand of old-growth cedar and hemlock forest “in perpetuity” on 160 acres that Lewis owned near the new headquarters site. Still not done, he met with Flathead County commissioners and extracted a promise to designate $10,000 as the county’s share of construction costs for a bridge to span the Middle Fork.

Glacier’s human landscape in 1916 was comprised chiefly of three elements. First were hardy homesteaders whose small deeded lands were grandfathered in with the establishment of the park in 1910. Most of them were subsistence farmers, tending small garden plots, running trap lines, and trying to make money from seasonal tourist businesses. Next were the wealthy, rail-borne tourists from the East and upper Midwest who the Great Northern hosted in its charming new hotels and chalets. Last was the small contingent of government personnel made up of a supervisor and a far-flung force of “thirteen first class rangers.”

The Glacier ranger staff of that period bore little resemblance to that of today. Without exception, the rangers were all male. There were 11 remote ranger stations, and the rangers’ days were filled with cutting firewood, building fences or cabins, clearing deadfall from trails, and patrolling for poachers or livestock trespassers on foot, horseback, and snowshoe. The vitality of the park’s wildlife was thought to be a barometer of the overall aesthetic value, and so poaching was seen as anathema. “Followed the calls of ravens and coyote tracks to a gut pile on the edge of Christensen Meadow,” wrote one ranger. “Must pay that bird a visit.”

Then there were fires. Superintendent Samuel F. Ralston praised his field rangers during the early teens for “… marshaling local railroad crews, homesteaders, neighbors and concessionaires” in joint efforts to suppress forest fires. There was one arrest in 1916 for poaching, and one visitor fatality from drowning. Some of Glacier’s field rangers received the announcement of their new parent agency only after they had returned to their winter quarters in late autumn from their remote duty stations. “News of our new governing agency seems level-headed enough to me. I only wish they have funds to purchase winter hay for my pack stock,” wrote one field ranger.

Meanwhile, hardscrabble settlers inside the park continued to graze, trap, and hunt, unfazed by the Park Service news. In late 1916, North Fork homesteader Ben Maes noted in his journal, “Word is at the post office that there is a new government agency running things. Wonder if common sense will follow. Must ride to Logging [ranger station] for the scuttlebutt. Too many trees down on the road to go there this week.”

By 1925, Director Mather had wielded his political clout and reputation to add dozens of new monuments and parks to the system. In matters dealing with concessioners cashing in on monopolistic enterprises in national parks, he yielded on nothing and doubled down on everything. Mather, more than any act of Congress, put the federal fingerprints on the agency’s parks. In Glacier, this meant dealing a telling blow to the powerful Great Northern Railway and its string of hotels scattered throughout the park. Not one to back down from a good fight, he pushed harshly against the Great Northern Railway’s efforts to sustain its unregulated monopoly inside Glacier with its subsidiary, the Glacier Park Hotel Company. Though he needed their private-side investments to create roads, visitor accommodations, and trails, he was eager to establish the preeminence of the Park Service and its authority to manage affairs. And so it came down to the great sawmill fight of 1925.

Since his appointment as director of the agency, Mather had been battling Great Northern officials to tear down an aging sawmill at the Many Glacier Hotel. It had been used in 1914 and 1915 to mill timber for the massive hotel, but had been abandoned since then. Termed an “eyesore” by Mather, he set about to test the will of his own agency against the entrenched strength of the Glacier Park Hotel Company. After years of letters, telegraph messages, and meetings, Mather traveled to Glacier in August 1925 and dealt with the sawmill personally. He blew it up.

He was accompanied by his teenage daughter, and used the occasion of her birthday to bring about the end of the long-festering mill debate. He arranged to have Glacier’s trail crews set dynamite charges throughout the mill structures and lumber piles, and then he invited hotel guests, park rangers, and local residents to witness the destruction. Thirteen charges echoed throughout the Many Glacier Valley as if to announce that there was a new sheriff in town. Great Northern vice president William Kenny later said, “It was the most high-handed, unwarranted and illogical thing that has probably ever occurred in any park, and committed by a government official, [sic] is particularly deplorable.” It made national news, of course, with the railroad protesting vigorously. But Mather and his new agency prevailed.

Still, Mather was a troubled man. On numerous occasions in his career he was simply absent from office — away for great lengths of time owing to what his colleagues referred to as “insensibilities of the mind.” Mather’s family members would often tuck him away for weeks or months in various insane asylums from Chicago to San Francisco. He would emerge, clear-headed and full of renewed vigor, to continue beseeching Washington bureaucrats for increased funding for his beloved parks. Then another bout of depression would seize him and his wife would sequester him in another sanitarium.

In truth, it was Mather’s assistant, Horace M. Albright, who conducted much of the heavy lifting during the Park Service’s early years. Letters and telegraph messages directed to Mather from far-flung parks across the nation were forwarded to Albright who shouldered the burden of making policy decisions in the absence of his supervisor. Albright was often the only official who was allowed to visit Mather during his periods of prolonged confinement. When Mather was on his game, he was the quintessential cheerleader for the growing system of the nation’s parks. But Mather’s trip to Glacier in 1925 was his last to that park. His health continued to deteriorate, and he suffered a stroke in early 1929. He withdrew from public view, and died a year later.

That first season of 1916, under the banner of the new agency, Glacier Superintendent Samuel F. Ralston recorded 12,839 visitors to his park. Ninety-nine years later, in 2015, the park hosted 2.3 million visitors. Although the Park Service may have begun with little fanfare, it is difficult to think of any comparable federal agency today that generates so much respect and nostalgia.

Tucked in hard against the banks of the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, today’s Glacier Park headquarters sit on the ground that Mather purchased back in 1916. Today there are warehouses, offices, apartments, homes, garages, shops, and the sturdy brick headquarters building. When Flathead County recently implemented a 911 locator system that required named streets throughout the county, the park responded by naming the main arterials at its headquarters Mather Drive and Albright Circle.

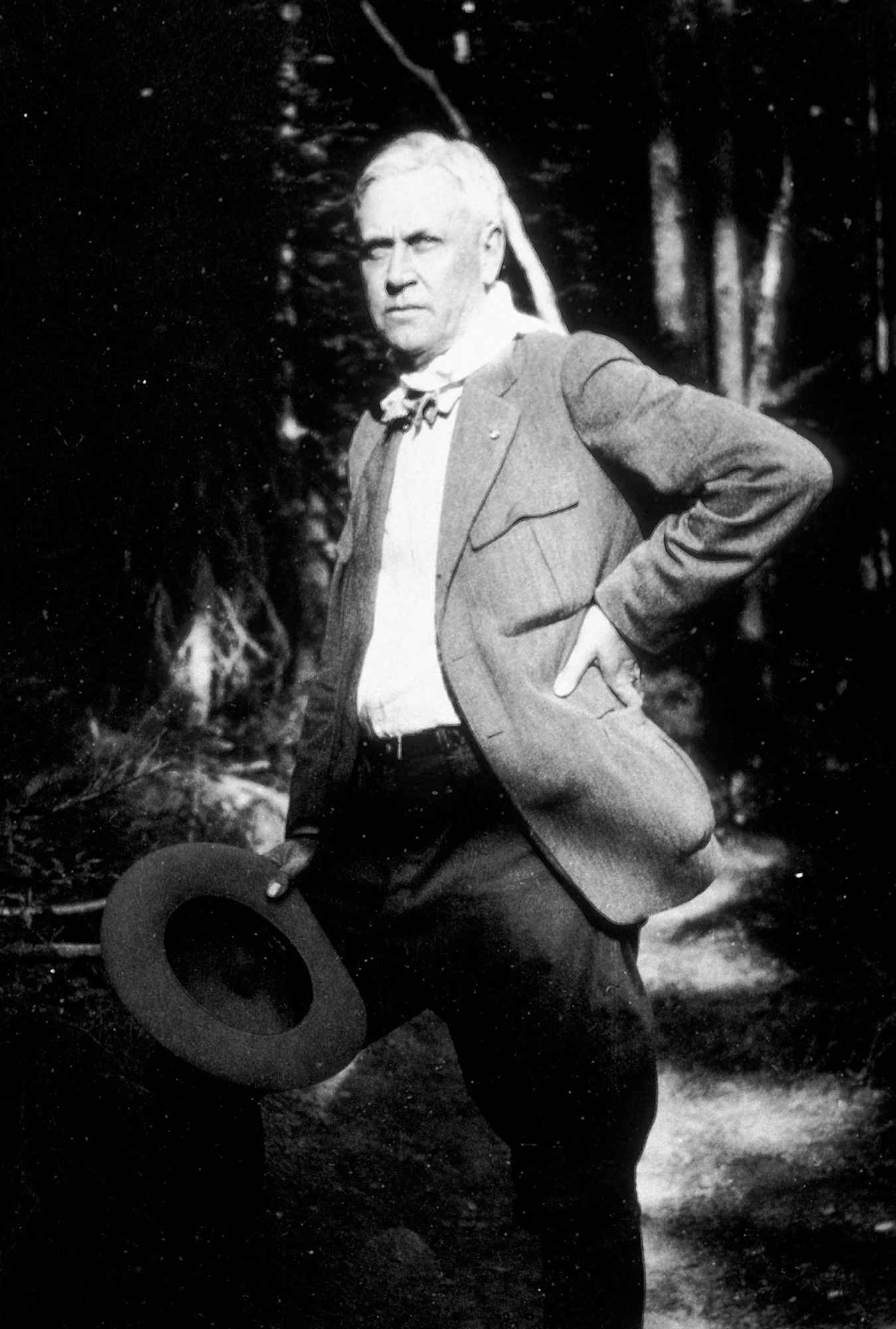

- Stephen Mather, first director of the National Park Service, occasionally used his personal funds to enhance Park Service holdings. Photo courtesy of Glacier National Park Archives

- Stephen Mather at Glacier Park Lodge with unidentified man, 1925. Photo courtesy of Glacier National Park Archives

- Stephen Mather on horseback in the Many Glacier Valley, Mount Gould and Grinnell Point in the background, 1926. Photo courtesy of Glacier National Park Archives

No Comments