30 Nov Standing Against the Wind

If you don’t believe Montana was once a land of skyscrapers, ask the wind.

Decades ago, the infinite huff of the mountains and the high plains was raked by more skyscrapers than soar today in any major city. Everywhere across Montana they stood: tall, slope-shouldered, wooden grain elevators.

They made “the classic statement,” said preservationist Carroll Van West, who in the early 1980s visited nearly every community under the Big Sky while working on a documentary project for the Montana Historical Society. Grain elevators proclaimed that “We might be in the middle of nowhere, but we do matter, and you can’t miss us: You can see us from miles away,” he said. “We are producing, using these tall sentinels to connect our ranches and our families to international markets.”

“We might be in the middle of nowhere, but we do matter, and you can’t miss us,” preservationist Carroll Van West says of the statement made by grain elevators, like this one on the Hi-Line near Lothair, Montana.

The tallest towers met the original definition of the word “skyscraper” as first used in the 1880s, meaning a building of at least 10 stories. For perspective on how dense they were in Montana, picture one of the world’s biggest modern cities. By today’s definition of skyscraper (a habitable building of more than 40 stories), the world’s leader is Hong Kong: It has 316. Next is New York City with 253.

The Old West had upward of 30,000 skyscrapers, said Bruce Selyem, founder of the County Grain Elevator Historical Society. A great multitude of them rose in Montana, where more land was claimed under the Homestead Act than in any other state.

Selyem, who lives in Bozeman, has dedicated his life to lovingly photographing the rustic ones that remain. He estimates that number now to be around 10,000. Most are dilapidated, sagging, and slowly blowing apart. “The old abandoned ones really hit a chord in my soul,” he said.

He’s far from alone. Which is why, in early 2016, when that ceaseless wind finally dealt a fatal structural blow to yet another elevator that defined the skyline of a small railroad town, something unusual happened. In Livingston, Montana, residents rallied — raising tens of thousands of dollars in just a few days — to purchase and preserve their grain elevator known as the Teslow.

When wind damaged the Teslow grain elevator in Livingston, Montana in early 2016, community members rallied and raised money to repair and save it.

“It’s always been a part of our skyscape, and losing it would have been to lose something special,” said Audrey Hall, a photographer who helped lead the effort.

Working with her was Lynn Donaldson, also a photographer, whose upbringing in the small Central Montana town of Denton taught her what grain elevators mean to a community. “We called them ‘The Denton Skyscrapers,’” she wrote in an email. “They are small-town skyscrapers, and towns just look weird without them.”

The West’s legions of early homesteaders planted the seeds, and up sprouted grain elevators. They were the bank vaults for treasures grown on the new farms that stretched to the four horizons. At first they held a few thousand bushels, explained Selyem. Quickly, they grew to hold tens of thousands. They towered beside railroad tracks, the busiest main lines and the most remote spurs alike.

Wagons (and later, trucks) wheeled loads of farmers’ grains onto platform scales on the ground floors of the elevators. The grains were then dumped down into the elevator’s basement, known as the boot, where they were tested for quality. From there, a gas- or electric-powered vertical conveyor — called a leg — lifted the grains up into the elevator’s cupola (or head). A mechanism called a distributor — basically a faucet for grains — then poured the different varieties down into individual storage chambers inside the elevator. When trains came, the grains were drained from the storage chambers back down into the boot. The vertical conveyor then raised them up into the head again. This time the distributor poured them down through a spout that emptied outside into a train car.

Weathered grain elevators stand 60 miles downstream from Livingston in Reed Point, Montana.

Today in Montana’s cities and towns, historic grain elevators teeter in a state of transition. Some, like the Teslow, have been preserved. Others have been repurposed as commercial spaces. Some are now homes. These are the exceptions.

“You’ve got to be creative about saving these, because they’re hulking, unwieldy buildings that don’t have a lot of windows, so they’re difficult to repurpose,” said Kate Hampton, community preservation coordinator for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office. “But it’s so nice to see when they are preserved, because they mean so much to people.”

More historic elevators stand forlorn, empty but for trash, dust, and pigeons. Many have been torn down, the memories of them fading. But those who remember miss them.

“That was kind of a landmark; I thought they’d be there forever,” said Randy Kostelecky, a woodworker in the Stillwater County town of Columbus, which in 2016 lost the silo and the grain elevator that had stood at attention for decades downtown. “You saw them every day; now you drive by there and [the downtown looks] naked as a jay bird.”

Added Columbus resident Steve Wood, “It doesn’t seem like the same town without them.”

Time and technology have worked against Montana’s original grain elevators, historians say. Yesterday’s wooden obelisks were not built for today’s trucks, tractors, and freight trains. Bigger, modern grain silos built of metal and planted at busy regional rail hubs did away with the need for smaller, older grain elevators dispersed all over the state. Also, railroad companies, which own many of the plots of land where grain elevators were built, see no profit in paying for upkeep and liability insurance for the outdated and unused structures.

Corporate and consumer food standards put historic elevators at a disadvantage too, said George Killham. He has worked in grain elevators around Montana for nearly 20 years. In his late teens, he helped pour wheat from one of three wooden grain elevators that stood almost exactly in the center of Montana, in the tiny town of Hobson.

“A lot of the reason these awesome, old-school ones with so much wood are not used anymore is they can’t satisfy the OSHA dust law,” he said, referring to the federal government’s Occupational Health and Safety Administration. “Two trucks go by and it’s dusty.”

A lone Teslow grain elevator stands in the Shields Valley in front of the Crazy Mountains in the town of Wilsall, Montana. Recently, a historic wooden grain elevator that had stood near this one was torn down.

A lone Teslow grain elevator stands in the Shields Valley in front of the Crazy Mountains in the town of Wilsall, Montana. Recently, a historic wooden grain elevator that had stood near this one was torn down.

One of Hobson’s historic elevators was recently bought on the cheap and demolished for salvage lumber, Killham said. He now worries about the last two. They stand side-by-side, their saddleback-roofed cupolas visible across miles of wheat fields. Their image is welded into the town’s sign, which beckons from the side of the highway on the entrance to town. It reads, “Welcome to Hobson, Pride of the Judith.” Killham wonders when that sign might be the only reminder that the town once revolved around its grain elevators.

“They’re an awesome landmark, and they’re vanishing,” he said. “Why doesn’t somebody put a little time into it, and put some tin back in it, and use it?”

In Bozeman, a couple did exactly that. The Anceney grain elevator stands in a fold of rolling hills coursed through by Highway 84. Built in 1914 and based on the name of Charles Anzionnaz, founder of the Flying D Ranch (which now is alive again with buffalo thanks to media mogul and conservationist Ted Turner), the Anceney elevator went into use around the time the nearby train station shipped out more cattle than any other on the Northern Pacific Railroad line.

Photo by Erik Petersen

In 2007, Bob Mannisto and Jill Baumler finished the seven-year process of transforming that 70-foot-tall elevator into their new house. Today the handsome, white home draws herds of curious visitors. Mannisto and his wife once gave countless tours. He said via telephone that he’s grown weary of the tours, however, and now prefers to fish the nearby Madison River.

Also in 2007, about 300 miles northwest of the Anceney, a granary (a historic building similar to a grain elevator) was turned into a small “pocket park” in the town of Kalispell. Ellen Bruyer Naumann, an elderly granddaughter of Julius and Susanna Bruyer (who built the granary in 1909), urged the town to accept the granary as a gift from her and her husband because it represented a “piece of Flathead County and Kalispell history.”

“We are on a time limit, as we do not plan to live forever,” she wrote that year, when she was 77, in a letter now on file in the town hall.

Kalispell gladly accepted the newly-refurbished yellow granary — which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places — and the 3/4-acre parcel of fenced land from which it rises. Today it lives on beside a school, a church, and a bike path. Speaking in May by phone from her home in Reno, Nevada, Naumann, now 87, said the gift makes her “proud.” She expects it to stand, “until lightning hits it and God figures it has been there long enough.”

In February 2016, in Livingston, after a winter storm blew the roof off the Teslow, its owner called in a wrecking crew. Photographer-turned-preservationist Hall said she and a handful of other inspired community members started working “virtually around the clock.”

Their group became a nonprofit called “Save the Teslow,” and it raised more than $48,000 to settle the elevator’s debt and buy it outright. The group also signed a new lease with the landowner, Montana Rail Link. By the time the cranes arrived days later, Hall said the group had “reversed the crew’s mission from demolition to preservation.”

Hobson, Montana, near the center of the state, once had three working grain elevators. Today only two remain, both out of use. George Killham, who helped pour grain from one of them when he was a teenager, said, “They’re an awesome landmark, and they’re vanishing.”

Over a cup of coffee in a cozy downtown cafe, she said she hopes the Teslow will one day become “a living museum” honoring the region’s art and history. The Teslow is a story with a happy ending. In Missoula, Bozeman, and Red Lodge too, other historic elevators have recently been repurposed as places to make and show art. But many towns in Montana don’t have the financial resources to keep their elevators. As the Teslow was being saved, 100 miles east in Laurel, a Montana Rail Link demolition crew came at night and used a front-end loader to topple the G.D. Eastlick grain elevator. Dozens gathered in the cold to watch the tallest building in town fall like an old, dead tree.

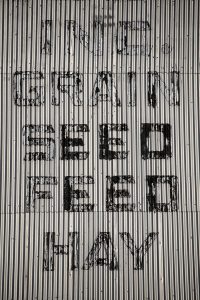

Between Laurel and Livingston stand twin historic elevators in the one-bar town of Reed Point. A sign painted onto the exterior wooden beams on one of the elevators — so weathered it looks sandblasted — still advertises for the company Occident Flour. (“Character and intelligence as well as wheat are put into the milling,” reads a newspaper ad from 1913). At its base, a pickup right out of a Steinbeck novel rusts next to a scrap wood pile. The wind blowing against the elevator’s high windows makes a hollow sound that harmonizes with the nearby swish of the Yellowstone River.

How long that duet plays on Montana’s landscape is up to the people who love small town skyscrapers. Because the wind, though her memory is long, does not love them at all.

No Comments