31 Jul Stacey Herries

Stacey Herries makes her art from a sunlit studio on the east side of downtown Bozeman, Montana. The space is large and airy, just steps from yoga studios, breweries, and restaurants. Simply put, it’s prime real estate. “Though I promise you, it wasn’t anything special back in 2015 when my friend and I bought the place,” Herries says with a laugh. “That was still before everything got crazy.”

Bozeman, like many Western ski towns, has changed a lot in the past decade. Blame the pandemic, a litany of popular television shows, or the celebrity draw of the Yellowstone Club — but the facts remain: Bozeman is booming. Since 2015, the population has grown by nearly 40 percent. With that has come higher housing prices and a fast-shifting culture. “This used to be a town where everybody kind of knew everybody,” says Herries. “That’s not the case anymore.”

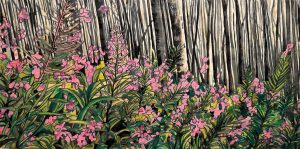

Firewood | ENCAUSTIC ON PANEL | 18 X 36 INCHES

Born and raised in Bozeman, Herries acutely feels the ache of change. She grew up biking down farm roads that are now four-lane thoroughfares, past fields now sprouting with luxury condos. “I struggle a bit with the way things are now, all the differences from how they used to be,” she says. “I’m very nostalgic, and I can get stuck in those memories.”

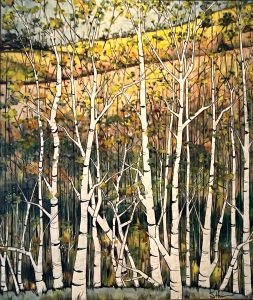

Painting the landscape helps her process her quickly changing community. “It’s important to me to paint this land as it is today,” she says. “Though sometimes I’ll paint it as it was, from memory. Remove a few buildings from the skyline.”

Herries approaches her subjects with a deep familiarity. The effect is a kind of beauty that’s dimensional and a bit complicated. There’s an amalgamation of emotions that comes through in each of her artworks: traces of sadness, possession, humility, and love. “Even some satire,” says Herries. “I like to tuck it in there.”

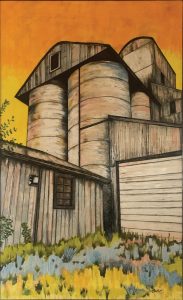

Retro BG | ENCAUSTIC ON PANEL | 42 X 24 INCHES

“Stacey’s work captures her love for Montana with such a unique, ethereal quality,” says Amy Kirkland, founder of Bozeman’s Altitude Gallery, which represents Herries. “It’s wonderfully textural. And I love that she keeps it close to home, so to speak.”

To understand Herries’ relationship with Bozeman, it’s important to know her story. There are bits of it on every street. “I live — now — in the same neighborhood I did when I was growing up. So, I’m constantly reminded of how my best friend, Robin, and I used to cut through the fields on Highland Boulevard and over the hill to get to Bogert Pool in the summer. We knew the owner of that land, and they didn’t mind us kids using it as a shortcut,” says Herries. “Things were really ‘country,’ I guess you could say. Local, gritty. There wasn’t this Western romance that exists today.”

In 1985, Herries became an art student at Montana State University after graduating from high school, immersing herself into the town’s tightly knit artist community. She points to a framed photo on her studio wall: a laughing man reclines before a large figurative painting. “That guy there? That’s Freeman Butts,” she says, identifying a founding father of Montana’s contemporary art scene. “And that’s me, actually, in that painting — I was a model for Butts a few times.”

Hoell Aspens | ENCAUSTIC ON PANEL | 48 X 36 INCHES

In the 1970s and ’80s, Bozeman’s art community was small but deeply connected. “We all knew one another. We all helped one another. We shared supplies,” Herries says. “That’s not so much the case anymore.”

After graduating, Herries made her first and only big move away from Bozeman, spending about 10 years on Long Island for the sake of her career in graphic design and her husband’s in academia. “But we missed it here, so we moved back.” For years after their return, Herries worked as an art and English teacher at Bozeman High School. However, her personal artistic practice remained constant and eventually became her career.

Herries is best known for her encaustic paintings. Encaustic is an ancient technique that originated with the Greeks around 500 B.C.E. The name itself — enkaustikos — means “to burn in.” At its simplest, encaustic is painting with hot wax and pigment, usually on wood boards. Some of the best-known surviving examples include Fayum funeral portraits painted by Greek artists in Egypt around 160–170 B.C.E. Even after thousands of years, the pigment in those works still holds its luster — a testament to the preserving qualities of wax.

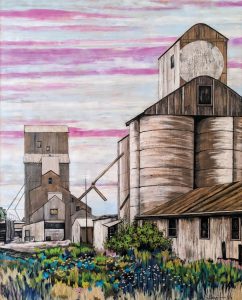

Grain Kings | ENCAUSTIC ON PANEL | 48 X 36 INCHES

There’s a range of approaches to working with wax. Herries, following the Greek masters, combines beeswax with tree resin. The resin strengthens the wax and helps her work endure.

The wax is fine as sand but soft; the resin is hard and crystalline. “It’s essentially hard sap,” she says. To make her waxy solution, Herries grinds the resin to match the wax’s texture, then heats them together over an electric stove until the mixture becomes malleable. Add a bit of oil paint for color, and voilà: an encaustic palette is made.

Her paintings come to life in layers. She uses thin birch panels because “the wax latches onto the wood nicely,” she says. She paints a layer of wax, fuses it to the panel with a blowtorch, and then repeats the process, building one layer at a time. “The fusing turns the wax into a single coat, so it’s stronger,” Herries explains. “But it also creates this sense of depth and richness.”

She first learned encaustic from Montana-based artists Vicki Fish and Shawna Moore. “It was 2009 or so, and my mom bought me an encaustic class with Vicki and Shawna. I just fell in love with the wax,” Herries says. “And I haven’t grown tired of it. Maybe I will, but for now, I find encaustic really works for the subjects I’m trying to paint.”

Those subjects are often local: poppies drooping in the July sun, aspen groves in neat rows, the trail through Story Mill Park. Her favorite muse is just next door — the BG Mill. An old grainery that’s slated for future development, it’s a standing example of Herries’ exploration of her changing community. “I do a lot of paintings of the grainery,” she says. “I love the old, rickety parts. I love the spray paint on it.” The mill’s wear is part of its charm. It’s a reminder that Bozeman — beneath the glossy surface of its new hotels and bars — is still an agricultural town. Structures were built for function, not fantasy. People used to work the land to get by here, not to live out a cowboy dream.

Bridger Glow | ENCAUSTIC ON PANEL | 24 X 30 INCHES

One of Herries’ paintings captures the mill at dusk in late spring. Its doors are closed, its silhouette dark against a wash of purple, pink, and blue sky. Wild grass and flowers grow around the base. At first glance, it’s a quiet, still scene. But linger, and the mind fills in the history: the crush of boots, the clatter of machinery, the farmers lined up to process their wheat. No wildflower could’ve survived that trampling. Herries’ painting holds both truths — the starkness of a quiet building in such a thriving, popular town and the ghost of its former glory.

Encaustic is a fitting medium for the nostalgia that drives Herries: It’s a meditation in preservation. Herries captures the Bozeman she knows, but even her memories are just layers fused over the Bozeman that existed before, and under the iterations still to come.

There’s a tension in her work between past and present, preservation and reinvention, all married to a constant truth. “I don’t own this place,” says Herries. “I wrestle with it — my own relationship with the land, the ownership I feel over its history, and my own firm belief that a place can’t really be owned. This place, all its beauty, belongs to all of us.”

Halina Loft is a writer and editor based in Bozeman, Montana. Before moving west, she worked as an arts editor for Sotheby’s in New York City.

No Comments