02 Jun Searching for Magic in the Magic City

April 2015, PPL Montana shut down its Corette Power Plant, an eyesore that was one of the first sites to greet people driving into the city of Billings from the east. A few months later, a local organization I’m involved with — the Yellowstone Valley Citizens Council — met to brainstorm ways that this prime piece of real estate could be utilized to enhance the community. We broke up into groups, drew maps, and compiled lists of possibilities, which included turning it into a park, a civic center, bike paths, ice rinks, and restaurants.

Sadly, after some discussion by the city council about buying the property, it was acquired instead by Talen Energy, a Pennsylvania company that, thus far, has done nothing with it. So, travelers continue to be greeted by a series of industrial complexes, distracting them from views of Billings’ most notable landmarks: the sandstone cliffs to the north — known as the Rimrocks and called “The Rims” by locals — and the Yellowstone River that runs along the southern boundary.

The renovated Carlin Hotel on Montana Avenue now houses several businesses, including the Craft Local brewery.

This turned out to be one more example of how Billings plays the part of the older brother who has all the potential and talent in the world, but just can’t hold down a job. We seem content in the role of the underachieving C-student who can never quite apply himself.

This is particularly puzzling because, when you look at Billings from a business perspective, there are few cities in the region with more going for them. It’s the most populated city in Montana, the state’s financial hub, and the place those in Eastern Montana count on for shopping excursions. It’s also the largest American city between Minneapolis, Minnesota and Spokane, Washington — a span of nearly 1,400 miles — and Denver, Colorado and Calgary, Alberta — a distance of almost 1,100 miles.

The Alberta Bair Theater, previously the Fox Theater, hosts a wide variety of cultural events each year.

So there is money to be made here, and plenty of indications that it is being made here, but somehow that’s never quite translated into something typically associated with affluence: culture. My Billings friends will immediately argue that we have a wonderful symphony orchestra, two solid theater companies (Nova Center for the Performing Arts and Billings Studio Theater), and the recently renovated Alberta Bair Theater, which hosts a wide variety of cultural offerings. All true. We also have two top-notch museums — the Yellowstone Art Museum and the Western Heritage Center — and, as of 2014, a state-of-the-art library designed by renowned architect Will Bruder.

But still, underneath it all, there remains a sense that the soul of Billings will always be more comfortable in a corner booth at a chain restaurant, with a bottle of Budweiser, a steak, and Garth Brooks playing on the jukebox.

Toucan Gallery is one of many businesses that came about after the historic buildings along Montana Avenue were restored.

I moved to Billings in 1969, when I was 12, and it was a wonderful place to grow up. All the cliches about being able to leave the house in the morning and play all day with your friends until your mom called you in for dinner were true. Plus, there was Cobb Field, where we got to watch our Pioneer League Mustangs play baseball. And more public parks and pools than a kid could ever need.

Before Rimrock Mall opened in 1975, and everything began expanding westward with big-box stores that you can find in almost every large town in America, the downtown was a manic beehive of locally owned businesses — like the Hart-Albin department store — and charming restaurants like The Windmill and The Golden Belle in the basement of the Northern Hotel. We even had three movie theaters downtown — The Babcock, the Fox (now the Alberta Bair), and The World. During the golden era of Hollywood, I remember seeing films like “MASH,” “Lenny,” “Klute,” and “The Last Picture Show.”

When the Montana Brewing Company moved into the restored

Montana Power Co. building in 1994, it helped to kickstart downtown’s revitalization.

But the mall’s arrival marked a sea change from which downtown Billings is still struggling to recover. When it opened, 24th Street essentially marked the edge of town. Since then, the expansion westward, as well as northeast into Billings Heights — which, at 31,000 people, would be the sixth-largest city in Montana if it was on its own — has pulled most of the business away from downtown. Like so many communities in America, the heart of Billings may still reside there, but its beat is exponentially weaker.

I moved away from Billings in 1984, but came back to visit my parents at least once a year, and observed the various stages of the downtown’s evolution. One of the most significant changes came when Montana legalized gambling machines in 1985. Many Billings residents lamented this development, as the best restaurants in town converted to casinos. It was an understandable shift — who could overlook how easy it was to install a few machines that brought in thousands of dollars a month — but it had an immediate impact on the overall aesthetics. When I was doing research for my book Fifty-Six Counties: A Montana Journey in 2016, I did a Google search for casinos and counted more than 150 in Billings alone.

The new Billings Public Library was designed by architect Will Bruder.

Throughout time, there have been efforts made to revive downtown, but one of the most influential campaigns was the result of social upheaval. Beginning in January 1993, a series of hate crimes led to a movement in Billings that eventually became known as “Not in Our Town.” A city council member at the time, Chuck Tooley, introduced an anti-hate resolution that passed unanimously. Still, the events came to a head a few months later, when a piece of paving stone was thrown through the bedroom window of a Jewish boy who had a menorah there to celebrate Hanukkah. The Billings Gazette published a full-page color picture of a menorah, which thousands of Billings residents displayed in their windows as a show of solidarity.

Tooley was elected mayor in 1995 and describes the pride that came out of that period. “We rose up with a sense of community spirit, against bigotry and hate, and the fact that we put ourselves at risk attracted national attention,” he says. “We received the Raoul Wallenberg Award for Civic Courage in 1997, and I think that was my proudest moment as mayor.”

The Rims that border Billings to the north offer stunning views.

That spirit and courage became the catalyst for a new vision for the downtown area. Community leaders Harry Gottwals and Kay Foster led an effort to gather input from residents through public meetings, focus groups, surveys, and personal interviews. “Montana law allows cities to create tax increment districts, and we made our downtown area such a district. This money allowed for private investments of more than $50 million over a 10-year period, bringing over 100 new businesses to downtown Billings,” Tooley says.

The most dramatic transformation occurred along Montana Avenue, which, over time, had become lined with a series of seedy bars and boarded-up buildings. With some of the most interesting architecture in Billings, many business owners made a concerted effort to restore historic buildings, opening things like Toucan Gallery and The Depot, a restaurant and brewery located in the old train depot. That restoration eventually spread south across the tracks, and now, the Arcade Bar — a notoriously shady establishment best known for stabbings — is home to the Russ Plath Law Offices.

Broadway remains one of downtown Billings’ busiest streets.

Many events have been specifically designed to generate more foot traffic, and so far, they seem to be working. Along with monthly art walks that have been held each summer for more than 20 years, downtown Billings now hosts a Saturday morning farmers market, and an outdoor concert series, Alive at Five, every Thursday. In addition, the Magic City Blues Festival has drawn huge crowds, and the High Plains Book Festival — a popular celebration of regional literature — has grown each year since its inception in 2002.

That sounds like a good amount of culture, right? But it’s the time between these events that provides the most accurate picture of downtown life: A walk on a random weekend night reveals vacant streets, nothing like the foot traffic you see in downtown Bozeman, Missoula, or along Last Chance Gulch in Helena. Dan Brooks, with the Billings Chamber of Commerce, is optimistic about the business opportunities that exist in the downtown area, but he believes an effort to create more housing there is key; more lofts and apartments, he says, would be a big boost for foot traffic.

Local artist Elyssa Leininger has painted several murals throughout downtown Billings and in other parts of the city.

While Brooks is encouraged by the influx of new businesses, he was disappointed that the city council shot down the multimillion dollar development proposal of the One Big Sky District in 2019. An outside investor named Bob Dunn, who organized similar projects in other cities, proposed a complex that would have included a civic center, restaurants, commercial space, housing, and healthcare facilities. On top of Dunn’s millions, the project required both Billings and the State of Montana to commit some financing for a venture that could have poured millions of dollars into the local economy. After initially being on board, some city council members, nervous about the risk, changed their minds. And once the legislature rejected the proposed development, it died a slow death, prompting questions from many Billings residents (including me) about why we resist change that would benefit us all.

Still, the effort to create a vibrant downtown continues. Two movie theaters recently opened there, after years of having only two options — both huge multiplexes west of town. Thanks in large part to local businessman Matt Blakeslee, the old Center Lanes bowling alley was converted to the Art House Cinema and Pub in 2012, offering more of the independent and foreign films that Billings moviegoers didn’t get a whiff of for decades. Blakeslee’s vision all along was to expand this venture into a multiscreen complex and, thanks to donations from the community, the Art House recently announced plans to move on to phase two. They also acquired access to the old Babcock Theatre, establishing a delightful policy of showing old classics. For the premier, they screened “The Princess Bride,” and it was packed. These two venues also provided space for another new venture when Brian Murnion founded the Montana International Film Festival (MINT) in 2019.

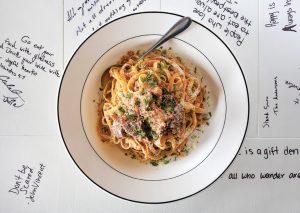

The Marble Table, featuring this delicious carbonara, is one of several excellent eateries that have recently opened in Billings. It was a 2022 semi-finalist for the James Beard Award for new restaurants.

In what was coined the Magic City years ago, the march of progress has made its intentions known. Downtown Billings will keep fighting an uphill battle for attention, and if the cultural offerings keep springing up as they have over the past 10 or so years, we will hold out hope that the city finds that magic once again.

No Comments