29 Sep Round Up: Walt Longmire Strikes Again

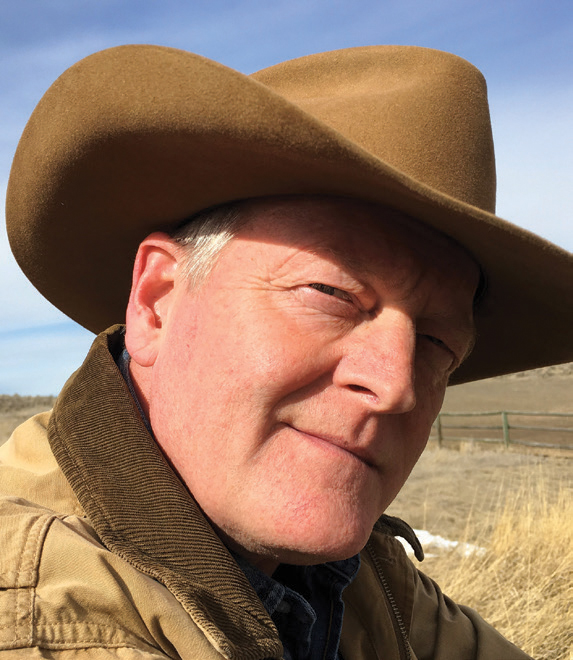

From his ranch in Ucross, Wyoming, population 25, at the foot of the Bighorn Mountains, near the border of Wyoming and Montana, The New York Times bestselling author Craig Johnson cranked out his 16th book in the Longmire mystery series, the basis for the Netflix original series “Longmire.” Titled Next to Last Stand, it was released on September 22 from Viking.

For those who are unfamiliar, the books trail the stories of Walt Longmire, sheriff of Wyoming’s Absaroka County, in which Johnson draws on his attachment to the American West to detail events that are tied to the area and the unique characters that he has developed within it. Johnson is the recipient of the Western Writers of America Spur Award for fiction, the Mountain and Plains Independent Booksellers Association’s Reading the West Book Award for fiction, the Nouvel Observateur Prix du Roman Noir, and the Prix SNCF du Polar. His novella, Spirit of Steamboat, was the first One Book Wyoming selection. Here he talks about his latest release and where he draws his inspiration from, among other things.

BSJ: What inspired you to write Next to Last Stand?

Johnson: You know, I’ve seen that poster of “Custer’s Last Fight” in every bar and saloon in the West, and one day I just decided to do a little research on it and found it really fascinating [the poster is based on a Cassilly Adams painting; 150,000 copies were distributed to saloons and dining establishments as a promotion for Anheuser-Busch]. I knew from looking at the painting that there were a number of historical inaccuracies, and when I found out about the connection to Budweiser and the destruction of the painting, I was intrigued to the point of thinking about incorporating it as a case for Walt.

BSJ: Do you have a personal connection to the story?

Johnson: Other than staring at the thing hanging above numerous bars across the country, no. I think the key element of any novel that relies on a historic incident or relic would be the point of access, and I had one right here in my Wyoming county. About 20 miles away is the Veterans’ Home of Wyoming, or as it used to be known, the Wyoming Soldier and Sailor’s Home. There were always guys sitting in their wheelchairs who would wave at passing traffic, and I had gotten in the habit of stopping every once in a while for a little conversation. They were amazing guys with some surprising histories, and they had been forgotten. This book gave me an opportunity to get them back in action.

BSJ: How did you become interested in Custer’s Last Stand?

Johnson: Oh gosh, I never was. … The battlefield is only about an hour from my ranch. Western history of the United States can be divided into categories, and one of those huge categories would have to be ‘Custer-ana.’ It’s one of those black holes of research that you can lose a year of your life researching. I guess I knew it was a mountain I was going to have to climb sometime, but I just wasn’t sure when.

BSJ: What kind of special research did you have to do for the book?

Johnson: After an entire year of research and reading every book on the subject I could get my hands on, I can tell you one thing: There are a lot of really crappy books about Custer out there. … There are some really marvelous ones that have come out more recently, but that’s one of the things that was particularly interesting to me — the fluctuating image of the battle and the man himself, and the way it mirrored the social and political leanings of the different periods. The other opportunity for gathering information was provided by my neighbors up on the Cheyenne and Crow reservations who had family members that fought in the battle. Their oral histories were quite a bit different from the mainstream, published works.

BSJ: What made you decide to feature the painting — and its history in American saloons — in this novel?

Johnson: Pretty simple. It may be the most-viewed piece of artwork in American history; an iconoclastic image that would link Walt and the area into a type of book I hadn’t written — an art heist. The last couple of books have been rather serious in nature, and I thought it was time to send Walt off on a lark in the art world, and possibly distract him with something inherent to his nature: research.

I’m on the board of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, which gave me an inordinate advantage in doing the research for the project and an insider’s look at how something like this investigation might unravel. I’m not the most knowledgeable source on art history, so for me, it was a new world too.

BSJ: What is the connection between Budweiser/Anheuser-Busch and “Custer’s Last Fight?”

Johnson: When the St. Louis artist Cassilly Adams’ painting had finished its nationwide tour, and it hadn’t realized the profits the owners imagined, it was brought back to St. Louis where the owners were at a loss as to what to do with it. So, they sold it to a local saloon owner, and it was plastered up on the wall behind the bar and became a conversation piece for thirsty art critics. Decades later, the bar went bankrupt and their greatest creditor was a then-small, local brewery by the name of Anheuser-Busch. Well, Augie Busch marches into the place and demands payment for the $30,000 worth of beer that they owed, and they tell him they can’t pay him. He looks up on the wall and says, “I’ll take the painting.”

Hauling it back to the brewery, he unrolls it and tells his marketing department that they’re going to make posters of the painting and send them out to every restaurant, bar, saloon, and rumpus room in America, and when they’re done, they’re going to be a much bigger brewery — and boy were they ever. After utilizing the painting for a number of years, Augie had a fit of philanthropy and gave the painting to the 7th Cavalry in Fort Bliss, Texas, in 1946, where it goes up in flames. … Or did it?

BSJ: Next to Last Stand is the 16th novel in your Walt Longmire series, and you write one a year. What keeps you writing them, and where do you get your ideas?

Johnson: Does it really seem like a lot? I feel like I should’ve written more. I keep my ear to the ground and whatever piques my curiosity is something that might interest Walt. For me, it’s not a segmented train of novels, but rather a continuous storyline of the sheriff’s life that I hope still has a long future ahead of it.

BSJ: How much of Walt Longmire is based on Craig Johnson?

Johnson: My wife Judy has the best quote about that: “Walt Longmire is who Craig Johnson would like to be in 10 years, he’s just off to an inordinately slow start.”

BSJ: Your books are so informed by the scenery and the landscape of Wyoming. What makes it such a great backdrop for your novels, and how does it inspire you?

Johnson: My ranch lies at the foot of the Bighorn Mountains near the border of Wyoming and Montana, and the nearest town has a population of 25. I think there’s a solitude that allows me the focus I need to write my novels. It’s hard to not be inspired by the world that surrounds me. I always enjoy going on the [book] tours, but I also appreciate coming home.

No Comments