29 May Road Trip: Anaconda, Montana goes from surviving to thriving

My first trip to Anaconda in 1973 was to compete at the Copper Empire Horse Show. The name was apt: The Anaconda Copper Company was a declining but still dominant force in Montana. The town, founded by Marcus Daly in 1883, was home to “The Smelter,” and you still hear the capitalization in people’s voices. For 100 years, Montana’s copper quite literally electrified America.

Today, the Anaconda Saddle Club grounds don’t look much different from a half-century ago. The buildings and barns are now on the National Register of Historic Places. But then, most of the area is similarly preserved. The Butte-Anaconda Historic District is a testament to the grit and determination of the people living there.

The Anaconda Smelter Stack is taller than the Washington Monument. Smeltermen’s Day weekend is one of the few times its grounds are open to visitors. | Photo by BRENDA WAHLER

Anaconda nearly fell into oblivion on September 29, 1980, when Atlantic Richfield Corporation (ARCO), the petroleum giant that sucked up the Anaconda Company, shut down The Smelter. A decision made in a far-off corporate boardroom changed Anaconda — and Montana — forever.

Anaconda rallied from this near-fatal blow and transformed from a hardscrabble industrial town into a recreation destination. Exiting from I-90 onto Montana Highway 1, perhaps a third of the vehicles sport Anaconda-Deer Lodge County’s 30-plate. The rest include vans bristling with mountain bikes, SUVs with golf bags or camping gear, and pickups whizzing by with toy haulers, boats, and horse trailers. Many are heading through town on the way to Georgetown Lake and the Anaconda–Pintler Wilderness. In the winter, ski racks dominate as people head up to Discovery Ski Area, or perhaps they go all the way over to Philipsburg.

Visible miles from town is the Anaconda Smelter Stack, sometimes called the Washoe Stack, or simply “The Stack.” It is the tallest surviving masonry structure in the world, rising 585 feet. It’s taller than the Washington Monument, which would nearly fit inside except its corners are a few feet wider at the base: think square peg, round hole.

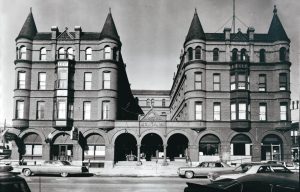

Anaconda’s iconic Montana Hotel stood tall and stately in the 1960s, before the top two floors were torn off and the building gutted. | COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The Stack is a monument to the past, but it also symbolizes the spirit of Anaconda. In 1982, ARCO blew up its twin, the refinery stack in Great Falls, ignoring local efforts to save it. In Anaconda, the residents dug in, stuck a thumb in the eye of the company, and saved their Stack to show how they ferociously survived the shutdown and, step by painful step, built a new future.

Last August, The Stack brought me to town. It’s mostly closed to the public, except on Smeltermen’s Day weekend, when it opens to carefully guided tours. Thanks to James Rosien of the Anaconda Leader, I got a coveted spot on Sunday’s 2 p.m. tour with Anaconda’s premier local historian J. Ray Haffey, a retired teacher, son of a smelterman, and author of Anaconda, Montana: Goosetown and West of Main 1945 ± 2020.

The area is quiet now — isolated, ghostly. The smelter plant complex that once channeled emissions to The Stack through a complex series of vents is gone. A chain-link fence surrounds it; no one goes inside except specialists with proper safety gear. Iron bands encircle the structure, helping keep it intact. But even dedicated preservation efforts cannot stop the occasional piece of debris, such as dinner-plate-sized fiberglass, laying quietly in the carefully planted native grasses reclaiming the land.

After visiting The Stack, I checked into the Marcus Daly Motel. Feyrouz (everyone calls her Fay) and Hassan Najjar have owned the place for 40 years. They don’t do online reservations; you have to pick up the phone and call.

Today, the Montana Hotel is reemerging after years of neglect. | Photo by JOHN SCHRANTZ

The Najjars epitomize the feisty spirit of both old and new Anaconda. Hassan’s grandfather came to America in the 1800s, saved his money, then returned to Lebanon. Next came an uncle, who reached Montana in 1921, changed his name to James Carpenter (Najjar means carpenter in Arabic), and ran a café and small hotel. Hassan’s brother followed in 1954. When Hassan arrived in multiethnic Anaconda in 1971, he landed a job at The Smelter — without anglicizing his name. His life was full of hope. Hassan returned to Lebanon in 1977, met and married Fay, brought her back to Montana, and started a family.

Then, The Smelter shut down. Struggling financially, the Najjars went back to Lebanon but landed amid even bigger troubles. Two weeks after they arrived, Israel invaded the country. After months of hardship and struggle, they returned to Anaconda for good. They found work but wanted to own their own business.

In 1985, an opportunity arose: The Marcus Daly Motel was for sale. It was a run-down but promising 1960s-style “motor hotel.” The bank took a chance on the Najjars with one catch: They also had to buy the Montana Hotel. That 1888 structure, attached to the motel, was a gutted shell that had lost its spot on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fay immediately went to work on the motel, scrubbing, cleaning, and removing fixtures caked with filth. To remove the decades-old smell of cigarette smoke, Hassan tore out sheetrock and insulation, taking every room down to the studs; then, even those were scrubbed to remove odors that lingered in the wood. Room by room, they transformed the Marcus Daly Motel into the spotless home away from home it is today.

The Upper Works Historic Trail overlooks the town, the Old Works Golf Course, The Stack, and the Pintler Range. Jack Nicklaus designed the 18-hole golf course, incorporating relics of Anaconda’s early smelters into the design: The black slag of cleaned tailings provides the unique “sand” of the bunkers. | Photo by BRENDA WAHLER

Meanwhile, there was the Montana Hotel. The structure, once Marcus Daly’s pride and joy, anchored his dream of making Anaconda the capital of Montana. He lost that battle to W.A. Clark in the infamous Capitol Fight of 1894 but remained determined to keep Anaconda on the map. The heart of the hotel was the lounge, with a hand-carved mahogany back bar and a 1,000-piece hardwood mosaic on the floor that depicted Daly’s favorite racehorse, Tammany. The mosaic remained pristine because no one was allowed to step on it; violators were obliged to buy the house a round of drinks.

The Anaconda Company lodged visitors at the hotel for decades, then sold it in the late 1950s to the first of many private owners. Each failed, but in 1964, the motel was added.

The decaying hotel went from bad to worse in 1976 when a contractor named Gene Higgins picked it up for back taxes. He sold off everything, from the marble fireplaces to the brass doorknobs. As a final insult, Higgins tore off the top two floors in 1978 before handing the mess back to the bank. By the time the Najjars bought what Higgins left behind, there was no stairway to the second floor; holes dotted the walls. More of a project than a struggling young family could handle, they separated the two properties and made their motel the best it could be. The hotel passed on through another four or five owners.

Smeltermen’s Day weekend in August commemorates the courage and grit of the people who built Anaconda. | Photo by BRENDA WAHLER

But, just as Anaconda itself recovered step by struggling step, the Montana Hotel is emerging from its own wreckage. Today, it is owned by the nonprofit Anaconda Restoration Association. The second floor remains off-limits to the public, but there is now a stairway. The building is stabilized, holes are patched, and a new lease on life has begun.

Inside, the restored lobby features new stained glass commemorating Anaconda’s proud history. Someone found the back bar in Seattle, brought it home, and reinstalled it. The association wants the Tammany mosaic back, but Daly’s heirs salvaged it from Higgins, and it is displayed at the Daly Mansion in Hamilton. I’ve listened to locals in both communities describe its near-destruction. I suspect that even to borrow it, negotiations will be delicate.

On Smeltermen’s Day weekend, most folks focused on the future. The Lady Hibernians led the parade of old cars, new fire trucks, and local candidates. On Kennedy Commons, amid Art in the Park, food trucks, and cornhole, Montana Deluxe played “extra strength” American Roots music. From nearby Deer Lodge, a couple in colorful shirts, Rick and Diane, came to dance away the afternoon. Diane summed it up perfectly: “There’s always something going on over here.”

No Comments