20 Aug Rob Stern: The Real Deal

FORGING YOUR WAY AS AN INNOVATIVE ARTIST IS NO EASY ROAD. But Rob Stern is not only creating art that stands out for its originality, he is also the co-owner of a successful art gallery, Samarah Fine Art in Whitefish, with partner LeAnn Libby. The gallery is named after his two children Sam, 13 and Sarah, 11.

“My kids think their dad is famous,” he laughs. “And they love having a gallery named after them. Beyond my art, everything I do is for them.”

Stern loves to paint, but is best known for his serigraphy, a complicated method of applying paint through a surface via a stencil process, layer after layer. The image is created like a painting, except each color of the image is painted on a different surface. There are thousands of creative choices that go into the intense, difficult process. Stern’s paper is hand-made in San Pablito, Mexico, by paper maker Mariano de la Loma.

In its simplest form serigraphy is created with a fine screen that is stretched tautly and attached to a frame. Certain areas of the screen mesh are blocked out with a glue-like substance, leaving other areas open and clear.

Paint is applied by raising the screen and positioning a sheet of paper on the table beneath, then lowering the screen on to it. A bead of ink is poured along one edge of the screen-mesh and pulled across the face of the screen by means of a squeegee, forcing the ink through the open areas of the mesh to the paper underneath.

The screen is then raised, the paper removed, and another sheet inserted. Once the sheets for the run have been finished, the screen is cleaned of ink and block-out and becomes ready for use again. The serigraph is built up of numerous applications of color and for each application the procedure is repeated.

“When I sit down to do my separations, they are all painted by hand,” Stern says. “My composition is all about emotion. When you make the choice to be an artist, if you want to give the world something no one else has, you need to lock yourself in the studio and develop your own thing. You dig it out of the dirt.”

While it can take as much as two months to get to the point of applying paint, the final step must be done in a day or two at most. Afterwards, each individual piece receives multiple layers of glaze by hand and the edges are torn and burned. The editions Stern creates are small, consisting of no more than 50 and sometimes as few as 17.

Stern’s road to his art career can first be traced to influences from his mother, a talented artist in many mediums. By the time he was 4, Stern was always drawing and sketching, creating art straight from his head. His father built race cars and his first paying job as an artist in his hometown of Billings was painting logos on the stock cars.

Even in high school, Stern produced designs and images for classmates, friends and businesses and began as an art major at the University of Montana. The academic art environment felt too traditional for him, but he took enough classes to graduate with a minor in art and a degree in business marketing. Throughout college, he was already busy as a professional artist, working with clients on logo designs and an assortment of other projects. He paid tuition with a mix of his art and bartending at Charlie B’s in downtown Missoula.

After college, Stern moved to Reno where he worked at a massive art galley at the MGM Grand Hotel, leading to other jobs with an ad agency drawing black and white fashion illustrations. But Montana was calling him home; he moved to Whitefish in 1989 where he started painting on canvas.

Patrick Nagel, a master at Minimalism and color composition, had a huge influence on Stern’s early work. As he explored a 1950s retro style, Stern suddenly transitioned to western themes.

“It was a really quick transition into the western work,” he says. “Something clicked. I had grown up on a ranch. We had hoedowns in the barn. My dad was a square dance caller. We had horses and pigs and chickens. But in a way, I think I had resisted it.”

Stern had grown up with C.M. Russell and Frederic Remington art plastered on the walls of his grandparent’s home. Unconsciously, the shift inside him happened in subtle ways.

“If I was mixing blue, it ended up as a gun barrel blue from the old single shot rifles,” he says. “Or an orange would become a tack color from the old saddles. I didn’t realize how much aesthetically and internally my upbringing had influenced me. It crystallized inside my whole being.”

Although the iconography of the West was boiling up inside him, as it exploded onto the canvas, he did not want to use traditional techniques or representations.

“I wanted to create something that was contemporary and traditional at the same time,” he muses, gesturing to one of his serigraphs on the wall of his gallery. “The presentation looks old and gritty. There’s some fog of history over it, but it’s very contemporary in its techniques.”

His techniques — and vision — are what truly make him an innovator. But Stern’s originality was heightened by studying an influential Montana artist who helped him realize that if he stayed true to what he was doing, everything else would fall into place.

“When I was growing up, the name Russell Chatham was always around,” he says. “I always loved his landscapes, even though I didn’t particularly like landscape painting. I was attracted to the minimal effects he used. The Tonalism.”

From the time he first saw work by Chatham, widely considered one of the world’s foremost lithographers, Stern set about decoding them, deciphering and looking at the process, understanding how to build color, create depth, and most importantly, compose. He considers Chatham the most influential artist he has ever known.

While Stern learned a great deal from studying his idol, Chatham is quick to note that originality is what stands out in Stern’s work.

“Rob Stern is the real deal,” says Chatham. “He’s not a poser. His art is truly unique — not something picked up from another realm. I really believe in what he is doing. Rob puts his whole heart into it.”

In 1991, Stern pulled his first serigraph, Wolf in Winter, after locating an old clamshell serigraph press. Today he describes himself as a “reluctant gallery owner” who seized the opportunity to open Samarah in 2004 and where he now represents more than 30 artists from Montana and the West, including Russell Chatham.

“We find ourselves where we are at,” he says. “Whatever experiences or influences we have up to that point is where we begin our journey. I don’t think serigraphy was a choice for me. It happened. It was conducive to the mediums I was using when I was younger, and it was more involved than sketching, drawing or painting. I can’t say I found serigraphy. I think it found me.”

He spends long hours in his home studio, but prides himself on the business he has been able to create, the artists he helps represent, and especially the serigraphs he is able to donate to local charities. As a fourth generation Montanan, Stern points out the importance of community and the tremendous support his business has received in the area.

“I get a lot,” he says quietly, “by giving. I often get a bigger kick out of selling someone else’s work.”

As a gallery owner, he is looking at ways to increase visibility, enhance communications with clients, network, and ultimately be more creative with his business, using his business degree to help his gallery thrive. But ask Stern if he’d rather be creating art or selling it and he’ll tell you the truth: he’d rather be in the studio.

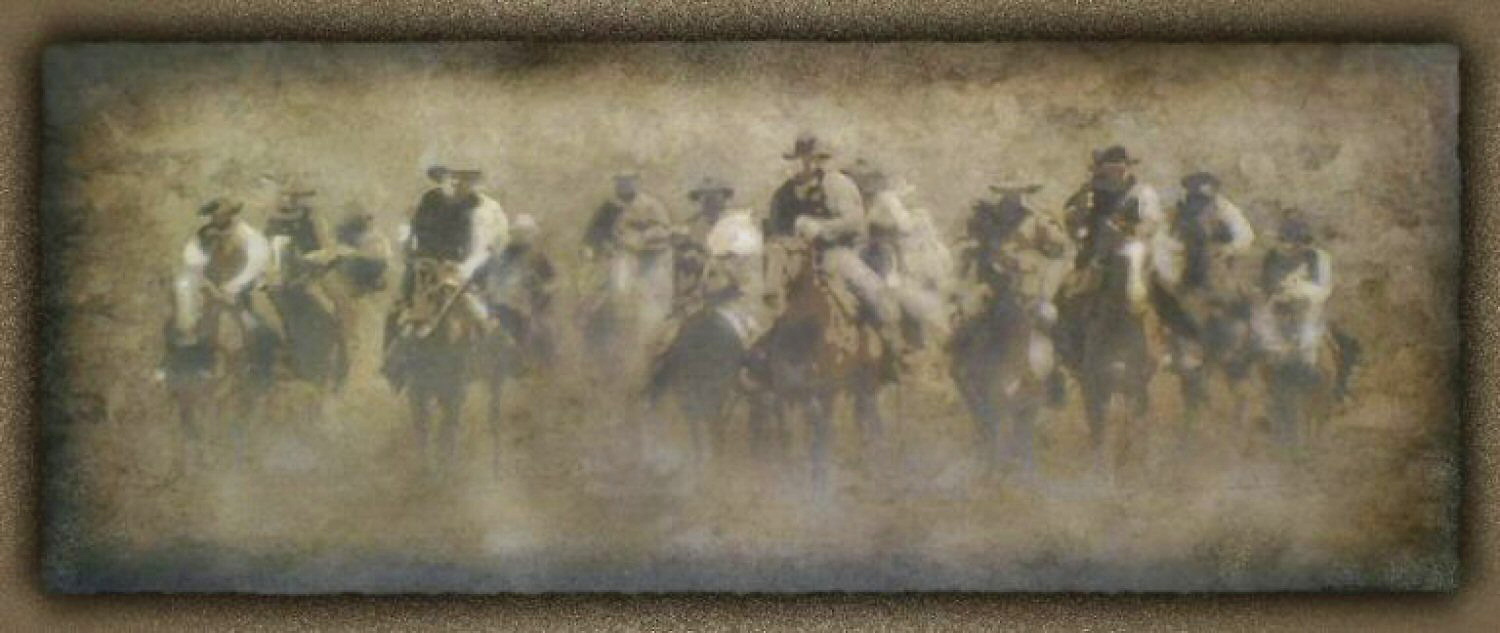

- “Seventeen” | Mixed Media Serigraph on Bark Paper | 20” x 50”

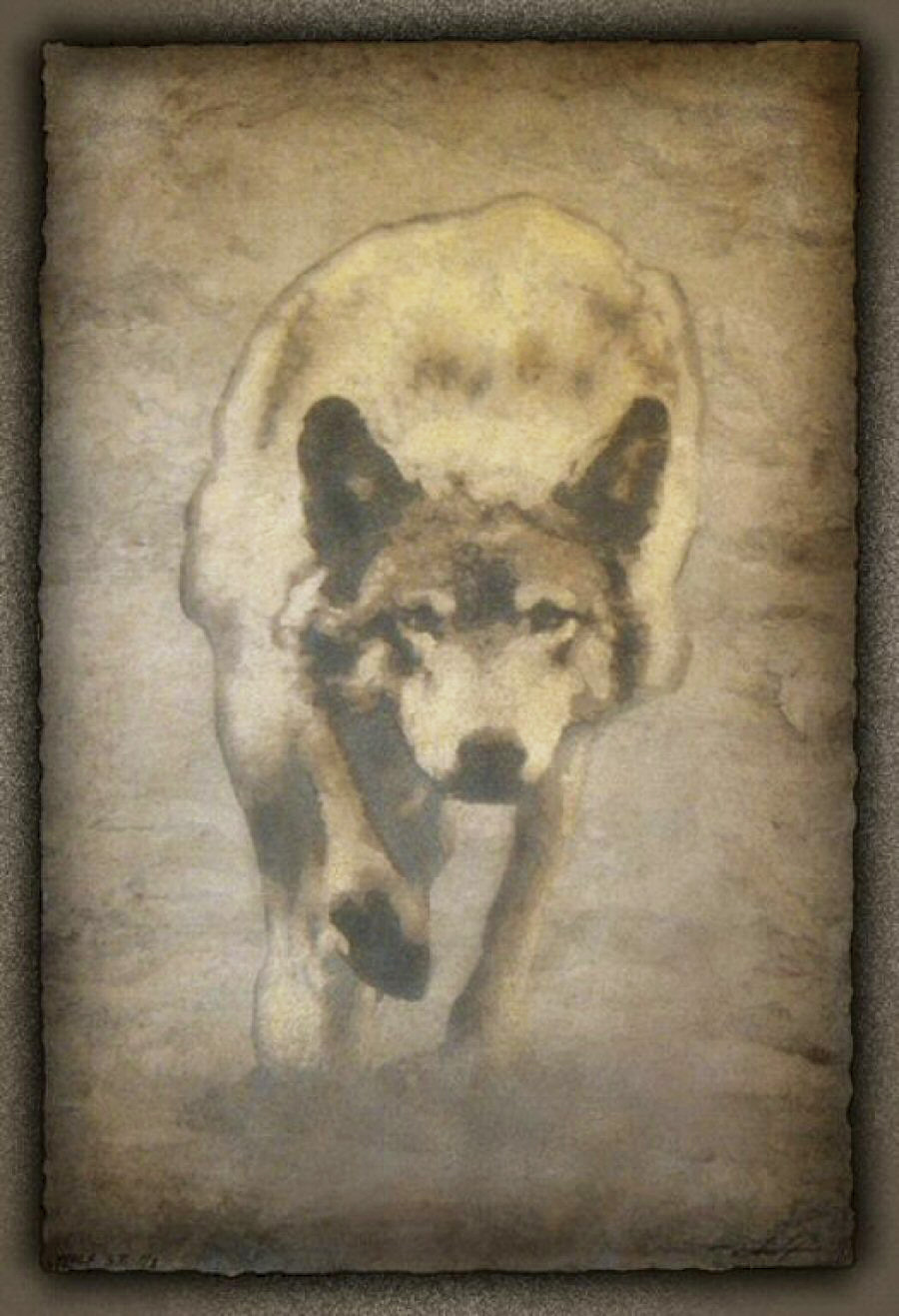

- “Wolf” | Mixed Media Serigraph on Bark Paper | 28” x 19”

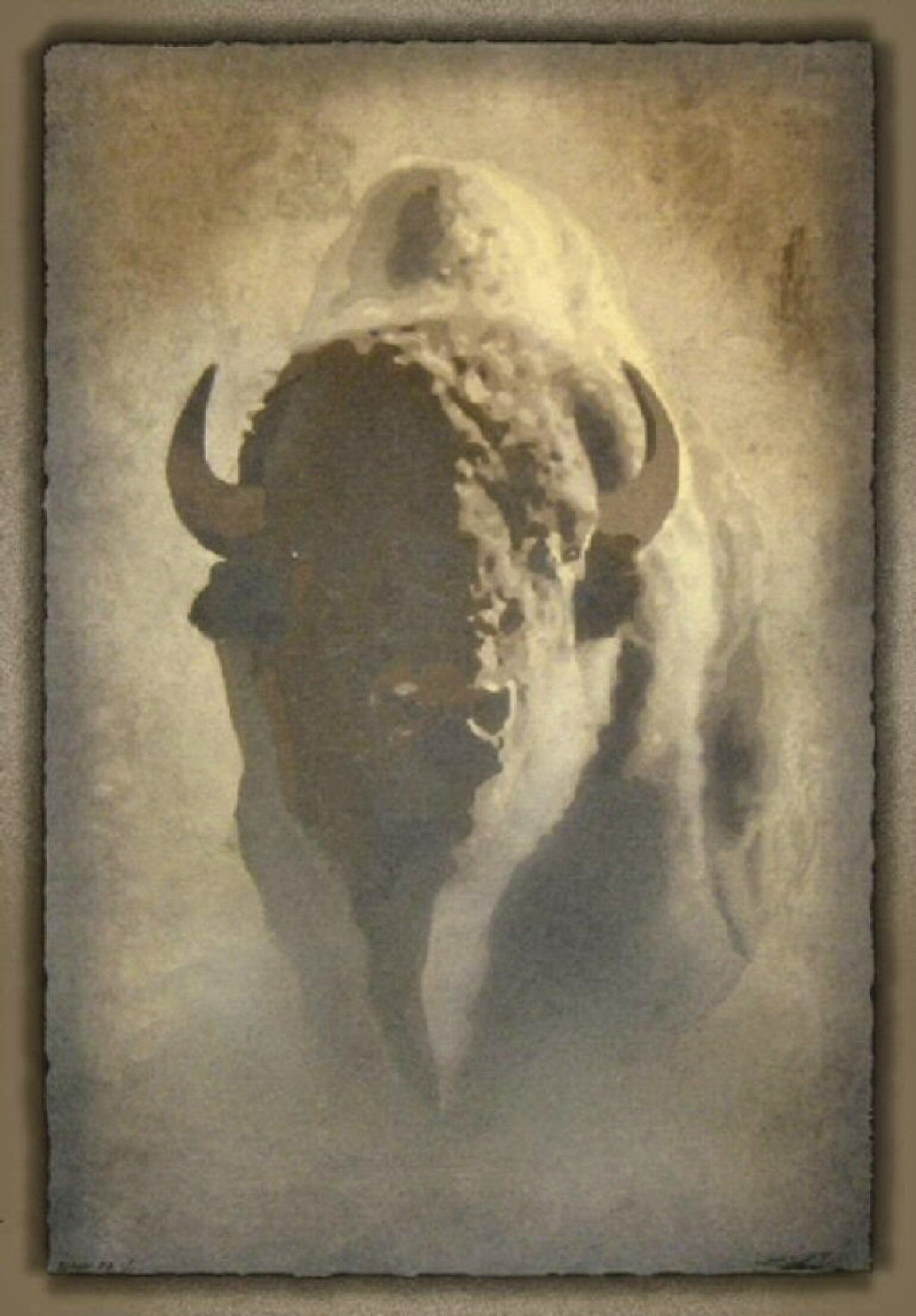

- “Bison” | Mixed Media Serigraph on Bark Paper | 36” x 24”

No Comments