17 Oct Books: Reading the West

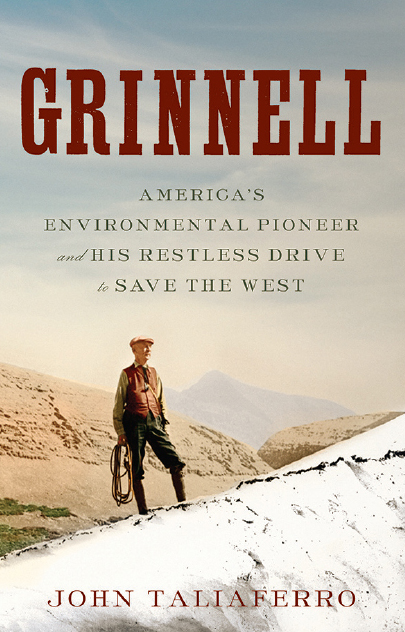

WHEN GEORGE BIRD Grinnell visited Glacier National Park in 1921, he was outraged when a stable manager insisted that the 72-year-old be accompanied by a guide on the park’s trails, the very ones he’d spent decades exploring and preserving. Grinnell wrote to Arno Cammerer, then the director of the National Park Service, to complain about the offensive treatment and also to request, “weapons to use against [any] wooden-headed ranger” who might ask him to comply with such a demand. Grinnell: America’s Environmental Pioneer and His Restless Drive to Save the West by John Taliaferro (Liveright, $35) is full of such anecdotes about Grinnell, creating a thorough and impressive portrait of the inimitable sportsman and conservationist, and offering depth and shading through his interactions with both the landscape he loved and the people he fought with, cherished, and revered.

Taliaferro’s well-researched biography of Grinnell captures both the facts of his life and the background and legacy of his experiences in the West. The author offers a rich context in describing Grinnell’s drive for the preservation of America’s special places and his energetic promotion of the sporting life.

Taliaferro’s well-researched biography of Grinnell captures both the facts of his life and the background and legacy of his experiences in the West. The author offers a rich context in describing Grinnell’s drive for the preservation of America’s special places and his energetic promotion of the sporting life.

Grinnell grew up in an aristocratic family on the former estate of John James Audubon in New York. He was the eldest son of a businessman and writer who seemingly knew everyone who was anyone in the West. Grinnell would eventually become closely associated with the region of Montana known as the “Crown of the Continent,” and this page-turning biography reveals both the story behind the places he championed, and the fascinating tales of an insatiable outdoorsman and life-long scholar.

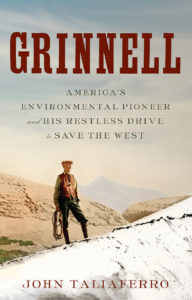

Two towering figures in the story of conservation and public lands in America receive a fascinating and compelling analysis in Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands by John Clayton (Pegasus Books, $27.95). Clayton, a regular contributor to Big Sky Journal, offers brief biographies of each of these giants, subtly comparing and contrasting their backgrounds and experience, while also debunking misconceptions about their areas of connection and disagreement. The brief biographies serve as a jumping off point for a thoughtful discussion of each man’s perspective and how it influenced their views on life and work for public lands. Their differences offer a natural point of conflict for Clayton’s thesis.

Clayton deftly portrays the spiritualist beliefs of Muir, who advocated for the preservation of untouched wilderness, and puts them in context with his background as an immigrant with a religious upbringing. Clayton also offers a view of Pinchot, who was equally devoted to wilderness but considerably more pragmatic, believing fervently in the potential for professional management of natural areas to be used as a means of conservation.

Pinchot’s background, youth, and education offer stark contrast to Muir’s venerable self-taught individualism. In describing how both shaped the way we think about America’s public lands, Clayton interweaves their stories and raises awareness about their longtime relationship that came to a head in the debate over the management of Yosemite National Park and the formation of the U.S. Forest Service. Clayton’s theory — the dynamic between the two men and their ability to come together from different backgrounds and philosophies to protect these special places through institutions that we now take for granted — is well-argued and supported by evidence and anecdotes in this engaging volume. The book includes historic photos of the men and the landscapes they strove to preserve, as well as those of numerous other individuals who were involved in the American conservation movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

ACCORDING TO SURVEYS, women now make up more than 10 percent of all hunters in the U.S., serving as one of the fastest growing demographic segments in a sport that hasn’t seen much growth in the 21st century. In her new book, Why Women Hunt (Wild River Press, $49.95), author K.J. Houtman asks women hunters from all over the country to tell the stories of hunts that changed them, and also to reveal the reasons why they don camouflage and head into the field in the first place. While a number of the women included have hunted their whole lives, some are relative newcomers to the sport. All tell personal stories that make for compelling and relatable reading, illustrated with stunning images of the women and their hunts.

CHRIS LATRAY, a Montana resident and member of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians, won the Montana Book Award in 2018 for his thoughtful collection One-Sentence Journal: Short Poems and Essays from the World at Large (Riverfeet Press, $15). This slim and artfully produced volume captures the mood of Montana’s seasons and landscapes in short poetry and prose, and includes elegantly simple line drawings throughout that evoke the landscapes and inhabitants of creeks and mountains, along with the realities of life in the wilderness.

Cold Country, a novel by Big Sky Journal contributor Russell Rowland (Dzanc Books, $16.95), is a suspenseful tale of murder and secrets set in Montana’s Paradise Valley in 1968. But it’s also a story about the relationships between generations of people living together in a rural, isolated place, the secrets they keep from each other, and the devastating reality of being both the new kid and a smart kid in a tiny schoolhouse where the options for the future appear to be bleak and limited. When a new family moves to town just before a well-known ranch owner is murdered, things unravel quickly as the web of interconnections becomes clear and neighbors become suspects. Rowland’s latest novel is a beautifully written story of place as well as a thrilling murder mystery.

CARL M. DAVIS’ Six Hundred Generations: An Archaeological History of Montana (Riverbend Press, $24.95) offers a tour through time — bringing new perspectives to 15,000 years of history through an exploration of archaeological sites, including long-inhabited areas, battlefields, and other locations. Through close examination of artifacts and evidence, archival photos, and color illustrations by Eric S. Carlson, Davis brings a richness and immediacy to the story of the first people to live in what is now the Treasure State.

No Comments