09 Jun Ranchland Summers

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE FOR ME TO BE even slightly objective about Carter County, Montana. This is where my grandparents’ ranch is located. It’s where my mother grew up, and where we spent almost every single Christmas of my childhood. It is where I spent the summer of my 16th year working 14-hour days, six days a week — an experience that transformed my life. To me, the Arbuckle Ranch was the biggest playground in the world, a place full of wonder and mystery, completely different from my dead-end street in Sheridan, Wyoming.

One day, when I was about 8, my grandparents took me to spend the day with the neighbors, who had a boy the same age. Kelly Kornemann was a typical ranch kid. He was quiet but friendly, with a dry wit and a great sense of adventure. When I went to visit Kelly, I knew it was going to be a good day. On this particular day, Kelly asked me whether I’d ever ridden a calf.

“Of course!” I said. This was a bald-faced lie.

But I was a Montana kid, and my dad had been on the rodeo team at Montana State University in Bozeman, where I was born. He was even a rodeo clown for several years, before he got stepped on by a bull when I was a baby, and my mother insisted that he give it up. So I just knew, in that way that kids know things without any evidence whatsoever, that I would be able to ride that calf like a real goddamn cowboy.

Kelly took me to the barn, and he fixed me up with chaps, gloves, and even spurs. He fastened a rigging around the calf’s torso, and showed me how to tuck my hand tight around the rope. We guided the calf into the chute, where I lowered myself from the rails onto his back.

Kelly whipped that gate open just like they did at the Days of ’85 Rodeo, and for about five seconds, I rode that calf like a champion. But suddenly, the calf stopped dead in its tracks, and I went flying. The way I remember it, I looked sort of like Superman. But I think there’s a very good chance I looked a lot more like someone falling off a calf.

I landed flat on my stomach, and my legs kicked up, so my spurs popped me right in the back. For the next 10 minutes, I was pretty sure I was going to die.

Kelly must have thought the same thing, because he rolled me onto my back, and he was crying like a baby.

And then Kelly did something that I didn’t understand at all. He crawled down to my feet and started to pull my boots off.

What Kelly and I didn’t know was that his father, Donny, was watching this whole scene play out from the barn, laughing his ass off. And for years afterward, both of our families had a good laugh over the fact that Kelly Kornemann wasn’t about to let his friend die with his boots on.

This memory has become more than just a funny story to me. It is an indication of one of the great gifts of growing up in a place like Montana, where we learn valuable life lessons from direct contact with the earth, and with the animals that share this marvelous place with us. Or do we share it with them? Either way, I have always cherished the fact that because of where I live, I have experiences that end up serving as metaphors for much bigger issues.

I also have found it a little maddening that because writers and artists from the West often focus on the connection between the people and the land, or the dynamic between people and animals, they are not taken as seriously by the literary elite. Some of the farmers and ranchers I’ve met in Montana are among the smartest people I know, and I’ve lived in Boston, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Seattle, where I met plenty of smart people. For some reason, any association with agriculture conjures up an image of ignorance in the minds of many people. But the fact is, working and writing about this part of our culture provides some of the most beautiful and natural symbols for our relationships with each other.

When you live on a ranch, you are exposed to the cycle of life in visceral ways that most people never experience. You see live birth, you see dead carcasses and watch them transform into decay, then bones, and finally just another part of the earth. These experiences change your perspective. They change your life.

You also experience the realities of raising food for a living. When I was a teenager, my uncle instructed me to hold a sheep’s head while he slit her throat, and it made me sick to my stomach. It also left me with a personal experience that I can apply to every piece of meat I eat for the rest of my life. I choose whether to be affected by how cruel some of these practices seem, or I can accept that this is part of the cycle of life. Many people would come away from that experience with a strong aversion to eating meat, and I can understand why. It was life changing for me. I also shot a deer when I was 16, and watching that graceful animal tumble to the ground in a heap left me shaken to my core. I never hunted again. But so far it hasn’t stopped me from enjoying a good venison sausage.

Rural Montana has a reputation for people who are stoic, and who have a difficult time expressing their feelings. This reputation is well earned, and it happens for a reason. When you are presented with these choices day after day, and when you watch the people around you make the choice to suppress whatever emotional response they may have to dealing with livestock, you learn to follow the crowd or suffer the consequences.

When I worked on my grandparents’ ranch that summer, and before I became a writer, it was the most satisfying work I had ever done. It was also the hardest by a long ways. My uncle roused me before dawn every morning and we worked until the sun was just above the horizon. I never even thought about grumbling about being shaken awake at 5 in the morning, as I had been conditioned in earlier years by my grandfather to know that when you are at the ranch, you do not sleep in.

I have never felt so exhausted from work, but in the best possible way, and this isn’t some kind of romanticized euphoric recall either. I loved it while it was happening. We stacked hay, in the days when the bales were still square and the hay stacker picked up about seven bales at a time. I learned to drive this machine as well as a baler and a swather, before I even had my driver’s license. And we moved cattle, docked lambs, branded, fixed fence.

I remember one day I was sent out to retrieve two bulls that had broken through a fence into the neighbor’s pasture. After fixing the fence where they broke through, I found the bulls and tried to maneuver these stubborn, mean animals toward the gate, a task that took what seemed like hours. It may have been hours. Finally, I got them through the gate, closed it, and headed back for the house. And as I was riding away, I looked back only to see them break right through the fence again.

That proved to be a crucial point of that summer, because a part of me wanted to go home and pretend it hadn’t happened. The petulant teenager in me didn’t want to have to spend another couple of hours trying to deal with these stubborn animals. But I knew exactly what would happen if I did that. I would be right out there, either that evening or the next morning, doing the same thing. There was no way in hell they were going to send someone else to do it.

So I took a deep breath and went through the same routine again. And this time they stayed.

One of the most valuable lessons I took away from that summer was the fact that when you’re doing work that involves animals and crops that depend on you to survive, there is no choice. You don’t call in sick; you don’t just decide to take a day off. These are not even options. The work ethic that came out of that summer served me well. And it gave me profound respect for the people who have done this work for their entire lives. It made me realize how completely wedded they are to their work. It is their life, whether they like it or not.

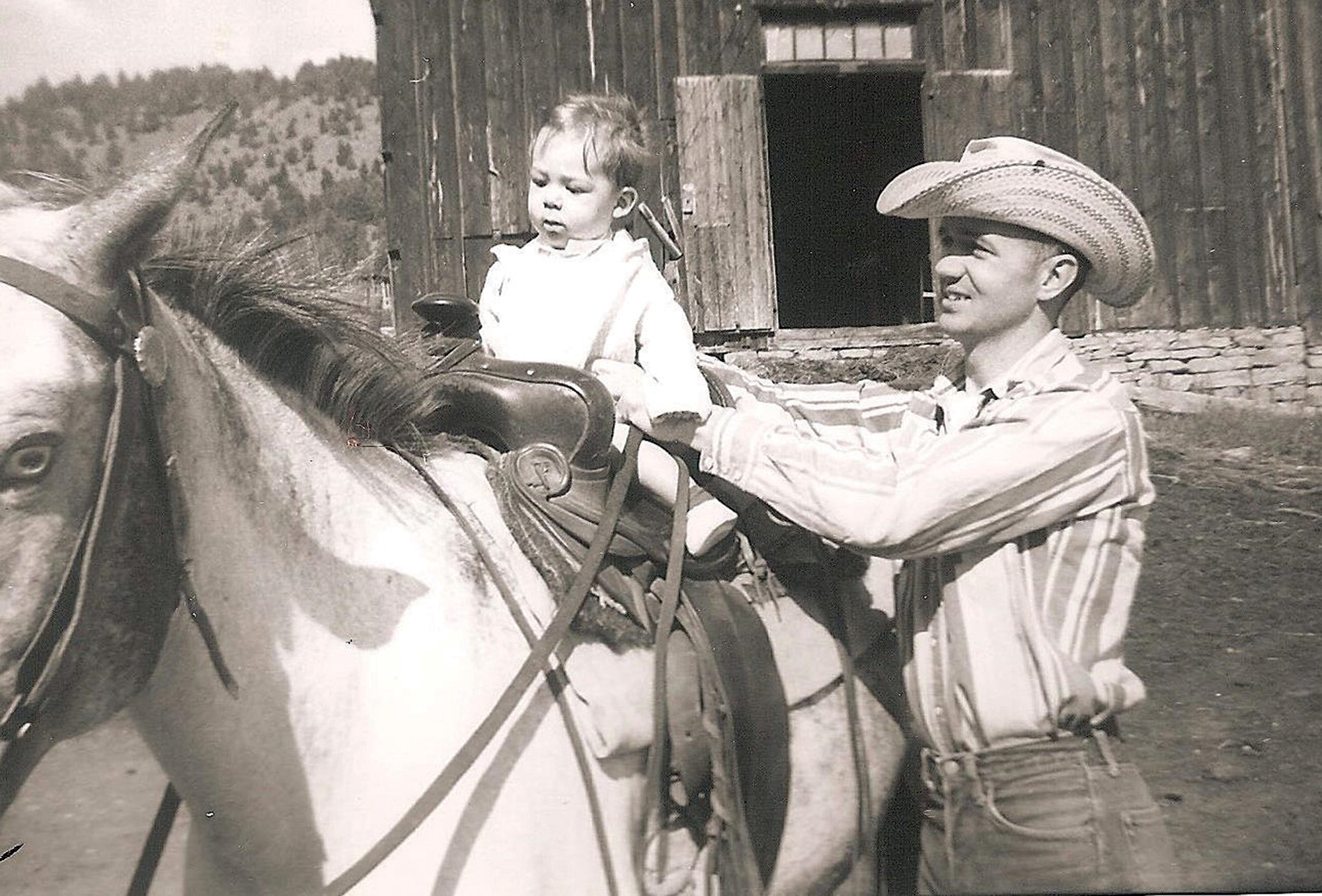

- The author and his father, in 1958, on the family ranch. This was the author’s first time on a horse.

- The author, in a red shirt, with friends and family in his grandparents’ house, around 1962. Kelly Kornemann is to the right, in chaps.

No Comments