14 Jul Images of the West: Progress at a Price

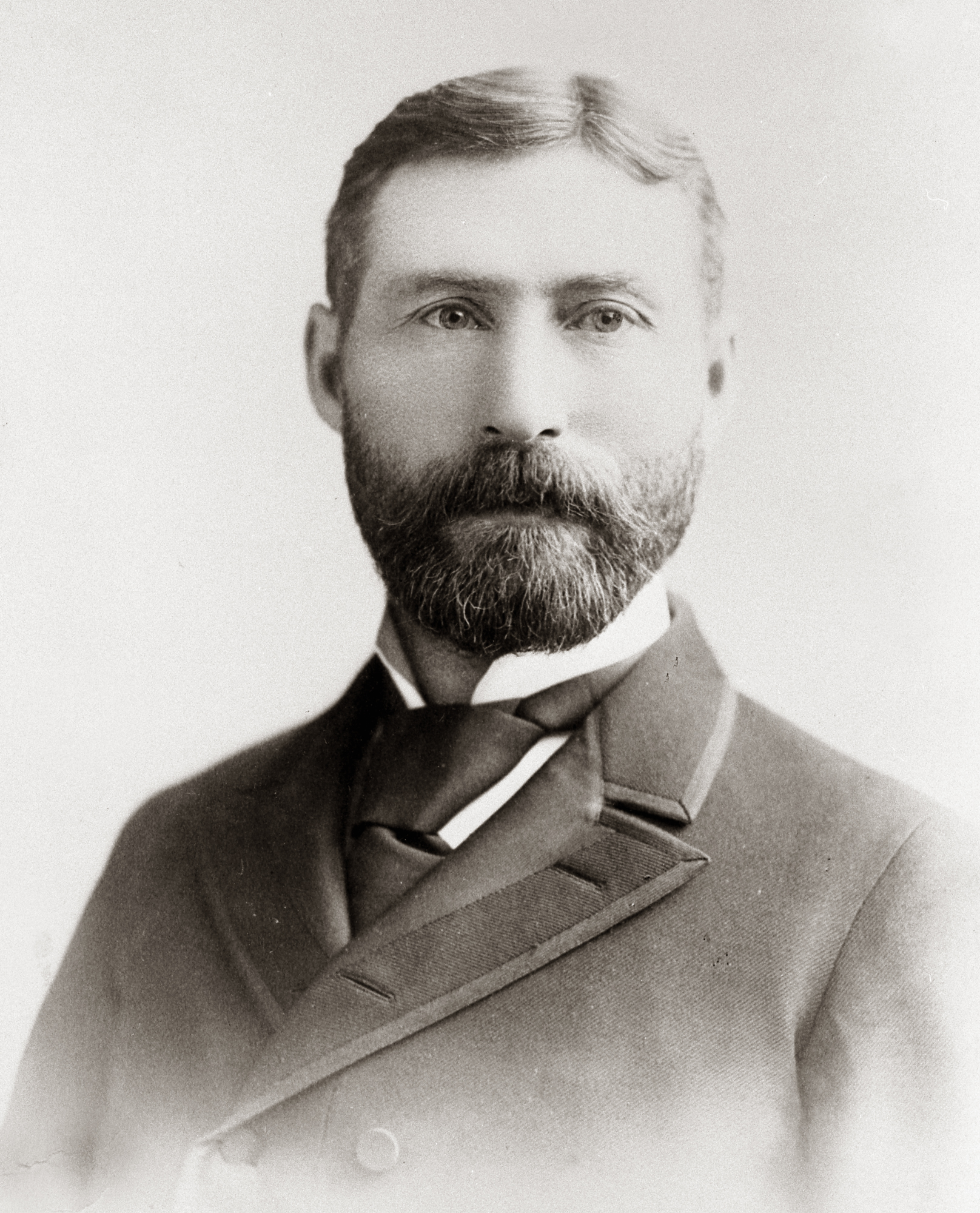

IN 1867 ANDREW B. HAMMOND arrived in Montana with 15 dollars in his pocket. Actually, half was in the pocket of his older brother, George. When he left, 30 years later, A. B. Hammond was one of the state’s wealthiest and most influential men. He was also among the most hated.

Today A. B. Hammond is largely forgotten; his name was consciously erased from collective memory. Shortly after his departure from Missoula, the town he largely built, the town council voted to rename Hammond Street. A few decades later, the largest building in town, the Hammond Block burned down. Finally, in 2008, the Bonner Mill, around which he built his lumber empire, closed.

More than any other single individual, A. B. Hammond was responsible for turning Missoula from a frontier trading post into a thriving commercial center. He built the railroad, making the city a transportation hub; he established western Montana’s lumber industry and built the Missoula Mercantile Company into the largest commercial enterprise between Butte and Portland. Why then was he so vilified?

It wasn’t always this way. When he took a job as a store clerk at a new mercantile run by Richard Eddy and E. L. Bonner, many in the frontier town of Missoula regarded Andrew Hammond as town’s most eligible bachelor. He was handsome, ambitious, congenial, fluent in French, a hit with all the ladies, and well-liked by the men. Competent and scrupulous in his accounts, in 1876 he became a full partner in the renamed “Eddy, Hammond and Company.” The firm began to grow by leaps and bounds, in large part due to Hammond’s astute business practices. From their main store anchoring the corner of Broadway and Main, the company established branch stores in Deer Lodge and in the Bitterroot and Flathead Valleys.

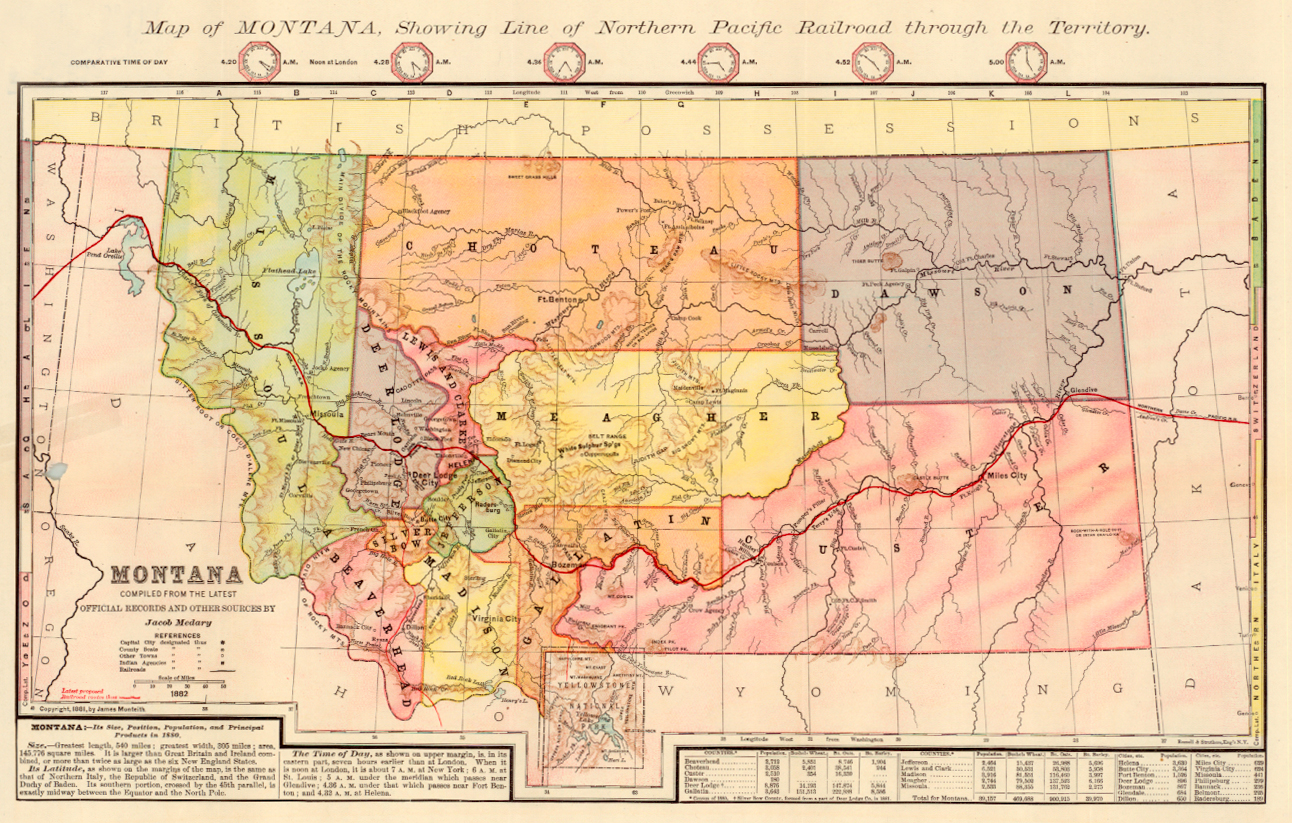

In July 1881, as the Northern Pacific Railroad was inching its way across the continent, Hammond spent a day at Flathead Lake with the railroad’s chief engineer. When Hammond returned to Missoula, he had in hand an exclusive contract to supply all of the railroad’s construction lumber from Mullan Pass to Thompson Falls, a distance of 175 miles. The massive timber requirements included 3,000 cross ties for every mile, plus lumber for tunnels, trestles and bridges. In addition, the Eddy, Hammond and Co. would supply the railroad with all its provisions: clothing, blankets, everything the railroad needed, save steel.

The railroad contract catapulted the Eddy, Hammond and Co. from a general store into the county’s largest employer and economic entity. For his part, Hammond rocketed from being a general manager of a local mercantile to one of the territory’s most powerful men.

While the size of the deal was certainly remarkable, what was especially surprising was that it gave an exclusive contract to build the roadbed and provide all of the construction lumber to a mercantile firm with no construction experience nor sawmills. Not only had the town fathers, C. P. Higgins, Frank Worden, and Washington McCormick donated hundreds of acres along the north end of town for a depot and rail yard, Higgins and Worden owned a sawmill, and McCormick had the largest lumber company in the valley. Naturally, these men felt cheated, and a rift soon developed within the Missoula business community that grew into a lengthy feud between Higgins and Hammond.

The following year Hammond became vice-president of the First National Bank of Missoula and a struggle erupted over control of the bank between Hammond and Higgins, the bank president and founder. While Hammond eventually triumphed and ousted Higgins from the bank, the conflict between the two split the town into two factions, with competing banks, stores, newspapers, political parties, and real estate development. Indeed, an absurd traffic grid, as result of the Hammond/Higgins feud, still plagues 21st century Missoula residents.

Essentially, Hammond began to develop a modern business practice, one that made sense financially but conflicted with tradition and the social ethic of small-town America in the 19th century. While many residents appreciated Hammond’s financial acuity and exactitude, others deplored his hard-nosed approach that offered little room for the exigencies of frontier life. The core of the Higgins/Hammond feud was the debate over which took precedence — the community or fiscal responsibility. Ultimately, as Hammond would demonstrate during the Panic of 1893, in which nearly every bank in Montana went bust except his, a community’s well-being depended upon its financial security.

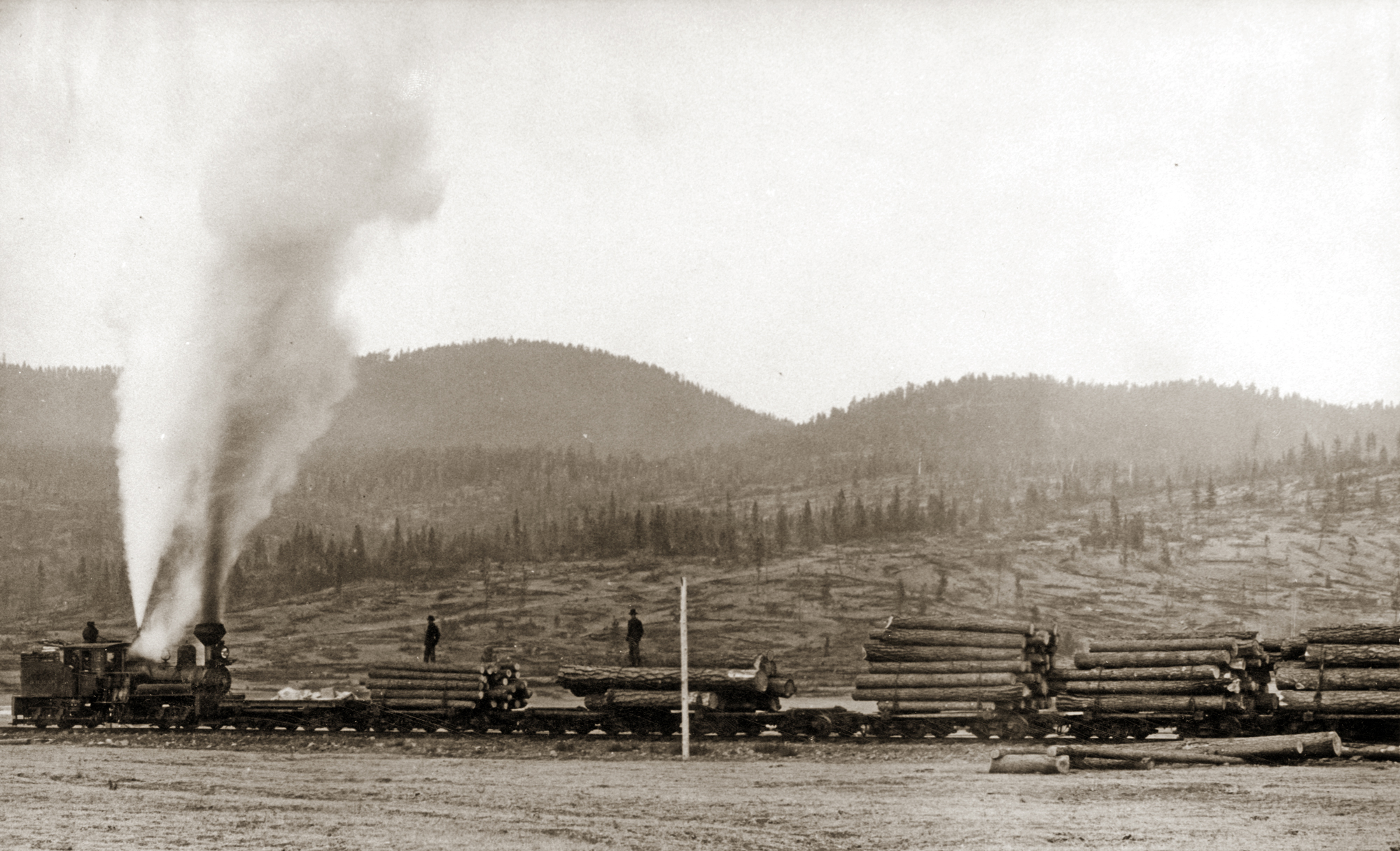

From his office inside the Eddy, Hammond and Co. building, Hammond supervised the railroad construction with the precision and authority of a field marshal. He hired loggers, mill workers, laborers, mule skinners — anyone who wanted work and was more or less sober. He subcontracted for grading and clearing the railroad right-of-way, purchased timber and lumber from independent loggers and mills, and sent specifications to New York for sawmills and other machinery.

To build the railroad, Hammond, Bonner and Eddy created the Montana Improvement Company (MIC), a new corporation backed by the Northern Pacific. Armed with a 20-year contract to supply all the railroad’s lumber and fuel needs from Miles City, Montana to The Dalles, Oregon, the MIC was well poised to become western Montana’s dominant business. Except that its activities were largely illegal.

As a subsidy for building a transcontinental line, Congress gave the Northern Pacific 42 million acres, the largest land grant in U.S. history. The railroad received alternate square mile sections along a 40- to 80-mile-wide swath from Minnesota to the Pacific Coast. The government also allowed the NP to cut timber on adjacent federal land for railroad construction. Hammond and his partners stretched the bounds of this provision with, “the word ‘adjacent’ being interpreted to mean practically anywhere in the United States,” reported Land Commissioner William Sparks in 1885. Furthermore, as the railroad grant had yet to be surveyed; it was impossible for loggers to tell it apart from the federal sections.

Montana resident S. H. Williams informed the Secretary of Interior that the MIC was “steadily chopping the government timber, and sawing it up into lumber and shingles for their own benefit, and pocketing the proceeds themselves.” But what was especially aggravating to locals was the MIC’s aggressive defense of timber it did not own, whether railroad sections or federal land. Williams complained that whenever anybody else attempted to cut timber for their personal use, the MIC would “make a terrible fuss about it, and threaten to put them in states-prison.”

Poaching federal timber, whether by individuals or corporations, was a common practice on the American frontier. Hammond and his partners had done the same as hundreds of others. But unlike most lumbermen who readily confessed their crime and paid a token fine, Hammond refused to admit any wrongdoing.

If Hammond had stopped logging once the railroad was completed, the government would have overlooked the trespass. But the arrival of the railroad in 1883 facilitated the development of the Butte copper mines, which had an insatiable appetite for mine timbers and cord wood for smelting. In 1884 Marcus Daly built the world’s largest copper smelter at Anaconda, which required prodigious quantities of cordwood for fuel. Daly contracted with Hammond’s firm to supply 10 million board feet of lumber. To supply the railroad, mines, and smelters, Hammond sent thousands of men to log the Clark Fork and Blackfoot Valleys.

Referring to the MIC as “bold, defiant and persistent depredators on the public domain,” Land Commissioner Sparks filed a formal complaint against the company in July 1885. The government charged the MIC with cutting $1,164,000 worth of federal timber and claiming control of the forests on railroad and government sections between Miles City, Mont., and Wallula, Wash., a distance of 925 miles.

Despite government lawsuits and injunctions, the MIC continued logging. In July 1886, the company finished building the much-anticipated Bonner Mill, the region’s largest. In its first month, the Bonner Mill produced 55,000 board feet (bf) per day, and within two years churned out more than 100,000 bf daily. With the mills cranking up, MIC began hiring all the lumber workers they could find. Exhausting the local labor supply, it advertised in St. Paul for more men. Although the mines still consumed a vast amount, much of this timber went to the new railroad branch lines being built by Hammond, Bonner, and Sam Hauser.

The completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad stimulated a decade-long burst of economic activity in Montana. Predicated on mining and the railroad’s ability to transport ore, banking, lumbering, merchandising, and agriculture all boomed. Montana’s population jumped from 39,000 to 132,000. Nearly every month it seemed a new mine, mill, or smelter appeared, with subsequent need for workers, fuel and timber. Ranchers added more cattle to the open range, now cleared of both bison and Indians. Farmers reaped high wheat yields and harvested the fruit from the Bitterroot orchards. With the railroad, Montana producers could export cattle, wheat, fruit, wool, and lumber in addition to minerals. And of course, metals, such as silver, lead, and especially copper, could now be shipped economically, stimulating even more development. Manufactured goods such as wagons, plows, harnesses, clothes, and furniture all flowed into the Eddy, Hammond and Co. and became available to consumers throughout the region.

While the timber lawsuits dragged through the courts, Hammond and his partners sought a more expedient solution — purchasing a politician. In the election of 1888 that ignited the infamous Clark-Daly feud between the two copper mining magnates, Hammond and Bonner conspired with Marcus Daly and Sam Hauser to defeat William Clark’s bid for territorial delegate. Each of the four conspirators controlled the electorate in their respective counties and instructed their employees on whom they should vote for. Each had their own reason for secretly defecting from the Democratic Party and supporting the Republican candidate, a young lawyer named Thomas Carter.

In a surprise to everyone but those on the inside, Carter won the election and within a month succeeded in getting the lawsuits dismissed. For the next

15 years — as a representative, land commissioner and U.S. Senator, Carter served Hammond’s interests in Washington D.C. As Bonner noted years later, “we did not make any mistakes. Carter was our friend in Washington.”

Abandoning the Democratic Party, Hammond moved to control Montana’s Republican Party. For the next three decades Hammond’s Missoula Mercantile Company (the successor to the Eddy, Hammond and Co.) dominated the county’s political, social, and economic landscape. Even to the point where the university president had to be vetted by the Merc before being hired.

By 1890 Andrew B. Hammond controlled every major business in western Montana, including the First National Bank of Missoula, the Missoula Water Works, the Missoula Street Railway, the Missoula Gazette, the Florence Hotel and the downtown blocks, the Missoula Real Estate Association (land speculation and development), the Bitterroot railroad, and the area’s only flour mill. Hammond’s Big Blackfoot Milling Company dominated region’s lumber industry. Underpinning it all was the Missoula Mercantile Company (MMC), the largest wholesale and retail business between St. Paul and Portland and western Montana’s largest employer.

If you lived in Missoula in 1890, you likely worked for one of Hammond’s enterprises; you bought your groceries, dry goods, hardware, farm implements, wagons and perfume from the Merc. If you wanted water or electricity you got it from Hammond. If you wanted to build a house you bought lumber from Hammond; if you wanted to buy a house, you got your loan from Hammond. If you were a farmer in the Bitterroot, you sent your wheat to his flour mill and then sold it to the Merc. And if you wanted a government job you went to Hammond who like Tammany Hall dispensed patronage through his bought politicians. And then when you died, you were buried in his cemetery.

Not surprisingly, Montanans rebelled against such domination. Missoula, like many Western towns, was settled by independent-minded entrepreneurs who resented and resisted the rise of a single economic power. Many saw Hammond’s economic domination as contrary to America’s republican tradition, especially when it coincided with his political activity.

In the 1890s, Americans grew increasingly concerned over the concentration of economic and political power, a movement that culminated in the formation of the Populist Party. As personification of the rise of corporate power, Montana newspapers called Hammond the “Missoula Octopus … whose slimy tentacles reach out and envelop nearly every farm and ranch and herd and even the forest land of the richest county in the territory.”

In response, Hammond argued that what was good for A. B. Hammond was good for Missoula. Seeking to mollify residents against the rising tide of Populism and answer the charges of monopoly, Hammond detailed his accomplishments in developing Missoula through “pluck, perseverance and industry” by building “railroads, hotels, sawmills, bank buildings, brick and granite blocks and the grandest mercantile establishment in the Northwest.” For Hammond, like many other businessmen, “public enterprise” was synonymous with private profit. All too often, however, the former was sacrificed for the latter.

In 1894 Hammond left Missoula for the greener pastures of Oregon and California where he assembled a vast lumber empire stretching from Arizona to Alaska. While his savvy business practices played a significant part in his success, much of his fortune was based upon theft, fraud, and political influence. Although Hammond regarded those who opposed him as jealous and spiteful, their resentment was largely based upon Hammond’s expropriation of public resources, in the form of trees, for private profit.

- Typical nineteenth-century logging crew. Hammond imported dozens of immigrants from his native New Brunswick to work on his crews. Many, such as Cyr and Thibodeau, left their names on Montana’s landscape.

- Interior of the Missoula Mercantile Company, circa 1900. As the super Walmart of its day, the Merc stocked clothing, hats, cloth, canned goods, fresh fruit and vegetables, furniture, carpets, saddles, drugs, farm implements, hardware, guns, saddles and shoes and more.

No Comments