30 May Outside: Taking Aim in the West

In memory of Rick Nyhart (1949 – 2024)

Sometimes we go back and see ourselves at a different time and place. We go back and look at where we started. Like the earth we inhabit, we evolve, age, live out our stories, fall into the arrangement of things, some dark mysterious order surrounding us. Sometimes the mountains have the last word.

In 1953, at the start of the Eisenhower years, my family and I lived in a 36-foot Spartan house trailer in Shoshoni, Wyoming. My father was a “tool pusher,” working for a construction company that was building a 125-foot-high water tower on the Wind River Indian Reservation a few miles outside of Shoshoni. He’d worked for Chicago Bridge & Iron Company since graduating high school in Killbuck, Ohio in 1948, the year he married my mother, the year I was born. I don’t remember a lot about living in Shoshoni, but I do recall the black-and-white photographs my mother took on her Kodak Brownie camera. After dinner, my brother and I would often sit with her at the small kitchen table and help paste the pictures into a red leather photo album she received as a wedding gift. The photos were mostly of the different towns and places we’d lived in for a few months before my father hitched the Spartan to the back of his GMC pick-up, moving us to start work on the next “tank,” usually in another state.

God Bless Our Mortgaged Home | DENVER, COLORADO | 1956 | COURTESY OF AL NYHART

The interstate highway system was just coming in then, so many times my father had to drive, trailer in tow, through the center of a town or city while my mother, driving her car, ran interference in front of him — driving slowly through a green-light intersection so my father could make the wide turn with the trailer.

There were photos of Wisconsin Dells; the Mackinac Bridge in Upper Michigan; the Ozarks in southern Missouri; the Iron Ore Range near Hibbing, Minnesota, where my father and his crew worked in 30-below-zero temperatures; a small town in southern Illinois where my fourth-grade teacher marched the entire class through our trailer to show them what it was like living in a mobile home — such was the novelty of life on the road during the 1950s. There were photos of the men my father worked with, their wives, and young children, friends my brother and I played with while the women got together in one of the trailers, sipped cream-and-sugar coffee, smoked Raleigh cigarettes with coupons on the back of the packages, and discussed the latest soap opera while a parakeet chirped at them from its cage in the corner.

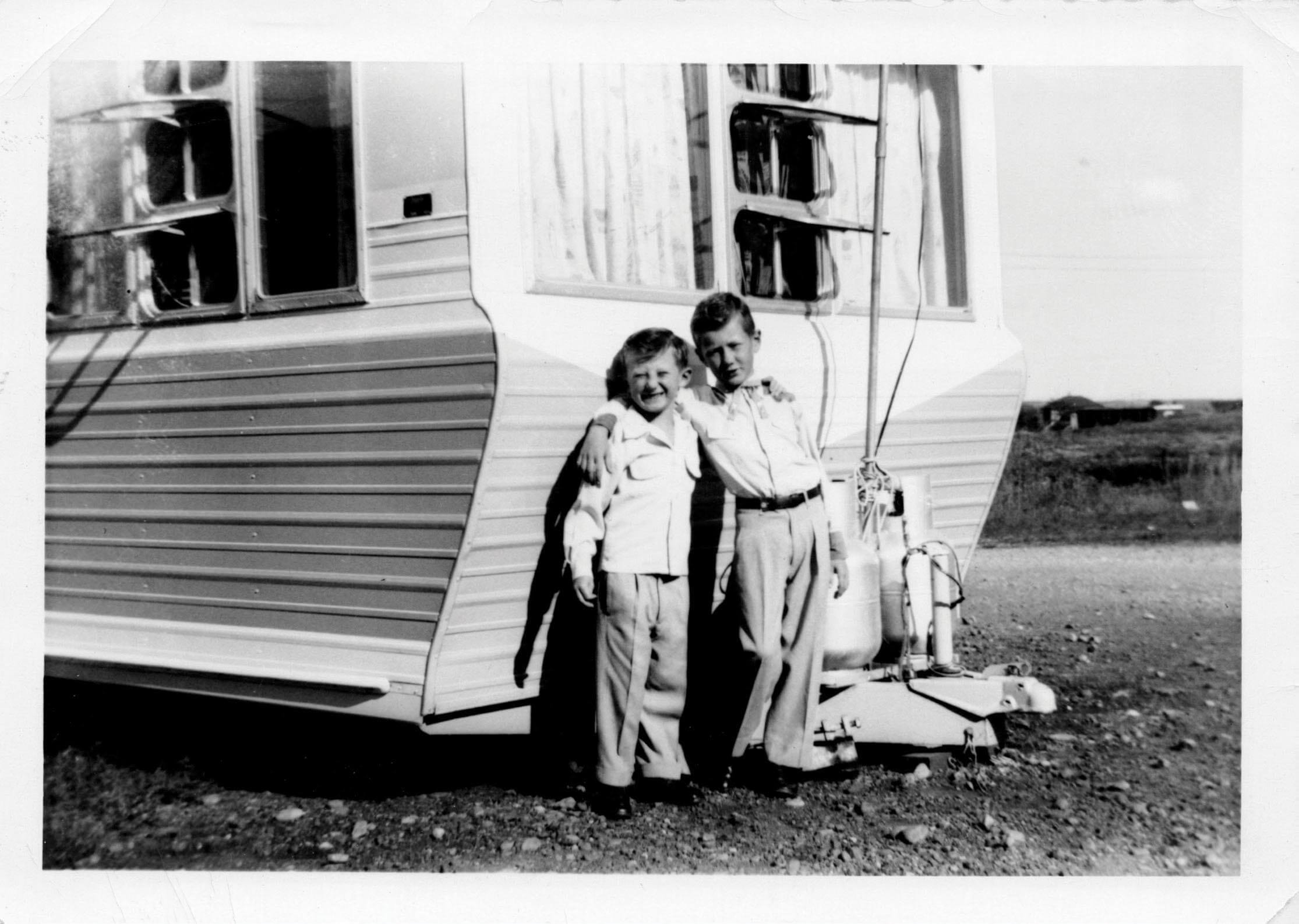

Home in the West | SHOSHONI, WYOMING | 1953 | COURTESY OF AL NYHART

But the pictures I would go back to, looking at again and again, were the ones taken in Wyoming: the job “out West,” where my mother spent half of my father’s paycheck at a department store in Thermopolis buying all of us Western-style clothes — cowboy hats and boots for my brother and me, as well as bright-colored wool shirts with faux pearl-snap buttons, leather belts with large silver buckles decorated with shiny turquoise stones, and a leather purse for herself with a galloping mustang stitched on the flap. There was a photo of my father taken somewhere near the Tetons. In it, he is standing sideways, legs spread wide apart, right arm extended toward the mountains. He is gripping a long-barreled pistol, though most of it is obscured by the brilliant flash from the gun’s muzzle. My mother snapped the picture at the exact moment he’d pulled the trigger. Had he hit his target? No one ever said. I’m sure he did; he didn’t miss much in those days. Next to it was a picture of my brother and me standing in the middle of a swinging bridge spanning the Wind River, just below the dam and canyon. The look on our faces shows how frightened we were, holding on tight to the steel cable railing, swinging high above the river.

Last summer, my wife and I took a short road trip to Wyoming from our home in White Sulphur Springs, Montana. After spending the night in Cody, we drove south from Thermopolis on Highway 20. Before we entered the first of three tunnels cut into the Precambrian rock mountains of Wind River Canyon, I pulled the car over and walked across the highway. I climbed up an outcrop at the base of the mountain. A small stream of water trickled from a crack in the rock. Brushing my hand over the hard surface of the 2.5-billion-year-old mountain, I felt that this was something I would keep, some mysterious rising that started here. I climbed off the rock, got back in the car, and drove through the mountain. As we exited the last tunnel, I looked to where I believed the swinging bridge had been years prior. It was gone, of course, but my wife pointed out the rusted relics of a few wire cables still embedded in the wall of the mountain.

Taking Aim | MINOT, NORTH DAKOTA | 1954 | COURTESY OF AL NYHART

I stopped the car, and we walked down to the river to get a closer look. I thought of my father then, working up high on that water tower, wondering if it was still there on the reservation. I thought of him stopping off at the Dam Bar after work to have a few beers with some of the crew and my mother waiting in the trailer at home for him, late again for dinner. I thought of Wyoming and the West and how, after billions of years, the mountains still speak to us, so that what I remembered — a trailer house parked on a barren lot in Shoshoni — was in the face of the Wind River flowing below us.

Al Nyhart’s first book of poetry, The Man Himself, was published by Main Street Rag Publishing Company in 2019. He lives with his wife, Cheryl, in White Sulphur Springs, Montana.

No Comments