31 Jul Outside: Stone Language

In September, all the water in Montana is low. On the west side of the Continental Divide, there had been no rain since early June.

Nikea and I left the creek and climbed the lifted palm of the drainage that held the lake. The basin lacked an outflow, so there was no stream cluttered with blowdown to follow up from below. We had to hike above the ridge’s brow, then down to the glossy pupil surrounded by the brown iris of the exposed lake bottom.

This lake appeared only to be fed by snowmelt, and the now-dried channels that funneled the thaw from the mountain’s peak had cut deep ravines we leapt across to reach the far shore. Over the course of four months, through evaporation and filtration of groundwater, the lake had lost feet of depth. The early-summer shoreline was obvious where the advance of the lush, alpine bunchgrass stalled at the hard line of exposed dirt.

Nikea, the author’s wife, fights a westslope cutthroat trout from a fallen cedar.

Last month’s story was written in tracks around the lake, and a sow black bear and her cub had read every word. Their paw prints followed where deer crisscrossed the western shore and scratched where a moose had swum across the lake and dripped water from his hide, leaving a trail of splashed sand. The pair stepped over mouse tracks, fine and small as pressed bluets, and inspected the 6-foot skid left by a bull elk who’d galloped down the shore, then slipped in the mud. We followed their prints until they disappeared in the elderberry.

Cutthroat trout rose to mayflies in the remaining water. Their dynamic world of expansion and compression had reached the zenith of drought, and I wondered how many survived each winter under months of ice.

We quickly made camp and then strung our fly rods. Only where a cedar had fallen into the basin could we crawl out far enough to reach where the trout fed. Balancing on a log while casting, we caught them with purple haze and caddis. We watched their sleek shapes as they rose from 5 feet down, often setting too soon. Those we did bring to hand were fat-bellied from warm months of hatches.

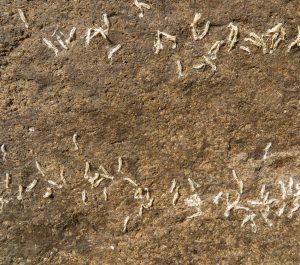

Then, we saw the stone. The side facing the lake was cleaved flat by the freeze and thaw of water over the centuries. The other split half was submerged 10 yards below in muck. From a distance, there appeared to be lines of text written on the giant tablet.

The shucks of mayflies dried to this rock after the insects hatched. The lines of these shucks followed the descending lake levels throughout the summer.

Five miles into a designated wilderness would be a strange place for graffiti, but humans are known to carry such ruin much farther. Not a mile back on the trail, someone had made a fire in the roots of a living cedar to enact some slow torture; the base of the tree scarred and scabbed over.

The lettering on the rock was white and thin. As I neared, it became clear — even as my uncertainty grew — that this was not a proclamation of humanity’s constant need for attention. Could it be some old cuneiform? Petroglyphs?

It wasn’t until I stood so close that I had to place my palm on the rock to balance that I realized the words were not those of human tongues. The shucks of tongueless mayflies had dried to the stone’s cheek, their collective metamorphosis the record of the lake’s summer.

Perfect as a ruled line, they charted the water level — and maybe other happenings beyond my sight — since the first June day when they crawled from the mud, up the rock, and hatched just above the lake’s surface. The stone faced south, and the shucks baked there, seared to the side with exoskeletal might.

Nikea releases a westslope back into the lake, wishing it good luck before the coming winter.

We read what we could. The faint lines grew bolder as the lake descended, and the hatches grew stronger with summer until they were a solid line — shucks stacked on shucks — in what we could only guess was the beginning of July. The distance between each hatch — a week? Ten days? — remained consistent at 3-inch intervals, except for a 6-inch band three-quarters of the way down the tablet. The poet in me thought about a stanza break. The naturalist wondered if the fish hungered after adjusting to the promise of the feast.

Below the break, the lines grew fainter until every mayfly sentence became incomplete with drought, giving way to the self-entombed caddis wrapped in pebbles. Ever since the lake retreated from the stone’s foot, the rock had waited for winter — still six weeks from where we stood — and beyond that, the short spring when the snow would melt and raise the water to scrape the slate clean for another year of mayflies.

In those long months, the cutthroat would rest silently confident in the promise that a time of plenty would return. With my hand on the stone, I believed in next summer, too.

Noah Davis’ second collection of poems, The Last Beast We Revel In, was published in April 2025. He works in conservation.

No Comments