25 Sep Outside: Christmas Morning

At 4 a.m., the first alarm sounds — not your typical electronic buzz or ringtone, but the vigorous shaking of collars belonging to two pointing dogs. Within seconds, there’s a cold muzzle nudging me to leave my warm bed to get dressed. This is really my own fault. I started my preparations for hunting season over the last couple of days and loaded a gun, hunting vest, and other gear into the truck last evening, all under the watchful eyes of my four-legged hunting companions, who are ready for the mountain grouse season to begin.

I measure time by the dogs that have passed in and out of my hunting life on opening day. Each has had multiple years in the grouse woods before they’ve become too old to climb the mountains or have passed on. I have memories of each of them in this landscape. Some good, some not so good, but all etched in my brain. I started with flushing dogs, big Labrador retrievers that worked close when things were right and maybe a bit too far when they didn’t go well. The transition to pointing dogs occurred when my last girl couldn’t make the climb in her final year. We walked around a small high-elevation opening before she let me know it was time to return to the car. While she managed a prairie hunt or two, I knew she’d never see the mountains again.

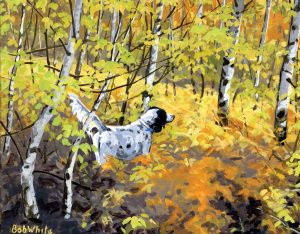

My transition to pointing dogs was unexpected, but not surprising. A friend had told me about an ancient breed of pointers that might fit my hunting style and, by chance, a little female happened to be available. Her first year in the grouse woods was predictable: excitedly running through the woods until she made contact with a bird, which she flushed before I could get there. Over time, her pointing instinct kicked in, and she became more cautious, more deliberate in her search. I shot her first grouse on a point she held for minutes while I climbed to find her. The look on her face — with a large bird in her mouth — was almost comical, but one I’ve learned to appreciate again and again over the years. I never get tired of the picture.

Our latest dog — a pointer and the first male in a long line of females — shows us that our girl is slowing as she approaches her 10th season. He’s a big runner, and on our first hunt he disappeared for what felt like most of the morning; when I found him, he was pointing the carcass of a long-dead deer. Once he understood the game, his points became steady, but he always wanted to run big. I’ve come to realize that, as long as he holds his point until I get there, I can live with that.

Forest grouse hunting in the mountains of the West requires a significant amount of work in most cases to get up to the vegetation and elevation where you might find birds. Add in the weight of a gallon of water for you and the dogs, a loaded hunting vest, and a shotgun, and the walk can sometimes be more challenging. Nonetheless, watching the dogs work while being treated to spectacular scenery and the chance for a grouse dinner make this all worth it.

The dogs are ready to leave the comfort of the truck and are eager to hunt, dancing around me as I strap on the vest and grab the gun. The sun is just starting to rise in the east and the air is crisp at this elevation. I can see where I’ll need to be in the next hour, sunlight shining through the distant firs above me. I complete last-minute checks and head out.

We climb for an hour through dense spruce and fir forest, the dogs sprinting through the trees as shadows, burning through the initial burst of energy before settling down to search the cover. I’ve rarely found birds in this dense forest, but it is a good place for the dogs to search and remember why they are here. They are back to me within minutes, greedily looking for water before we continue the climb.

When we are midway to the top of the ridge, the forest transitions into larger openings covered in sagebrush interspersed with grasses and forbs. The sun crests the ridge, and the frost on the grass glimmers as it begins to melt. Long shadows from the trees keep the air brisk as we continue to climb.

The dogs recognize the changes as well, their search becoming more directed to the openings within the canopy. Within minutes, both of them have disappeared and there is silence on the landscape. For the hunter, that is a promising sign. I look north to where I’ve seen them last, check my GPS, and realize that both dogs are on point almost 100 yards in front of me. I click the barrels of the shotgun in place and work toward their location.

Both dogs are together, the older dog a few yards behind the youngster, who is intently focused on an opening near a large fir tree. As I approach, three young grouse rise from the opening. I fire a shot, and one of them falls to the ground while the other two head downslope to the safety of the forest. The young dog races to the bird, looking unsure how to pick up his prize, while the old girl, a veteran of this game, scoops it up and brings it to me: our first dusky grouse of the season.

In our area of Montana, we hunt dusky grouse, split from their coastal cousins, the sooty grouse. For years, both were lumped into the “blue grouse” category until they were recently determined to be separate species by the American Ornithological Society. While I’ve handled both in my travels, it is sometimes hard for a non-bird biologist like me to tell the difference. I’ve heard forest grouse, particularly dusky grouse, called “fool hens,” and certainly in the spring mating season, strutting males can be almost comically easy to catch. While in the woods one spring, a co-worker and I had a big male dusky strut around us for the better part of 10 minutes while we took pictures and finally caught this character in a jacket. When we released him, he continued to strut around us until we left his territory.

Grouse can sometimes be easier to hunt in early fall because they are found in family groups that forage in larger openings and tend to hold for my pointing dogs until I get a chance to flush them. This all changes as the season progresses and the birds become more wary.

I water the dogs and settle them down before moving up the slope to continue our hunt. As the sun climbs, the temperature starts to rise, and I realize that our hunting window may be shorter on this warm late-summer morning.

As I hike up the mountainside, the dogs disappear again. I look down at the GPS and it indicates that they are on point 300 yards upslope. I start the climb, resting every so often to conserve my energy for when I reach them and hopefully have a shot. I get within 75 yards when a large grouse leaps from the ground and disappears before I can get a shot. This is clearly a bird that has been educated and is most likely a holdover from the previous year. As I reach the dogs, I give them the “alright” sign, and they frantically search in front of them, wondering what happened.

I call them to me and give them lots of water and a few snacks before continuing uphill. Within minutes, the dogs go missing again, and as I look at the GPS, I realize that not only are they not together, but both dogs are on point at different locations almost 200 yards apart. I’m faced with a choice. Do I go to the older dog first or the younger one? I decide to find the young dog first, rationalizing that the older dog might hold the point longer and recognizing the lucky possibility of shooting the bird in front of the younger dog. While this seems logical, things rarely work the way you’d like.

The young dog holds point until I’m closing in, and a bird flies. I’m able to get one shot off, and miss, before the bird is out of range. I apologize to the young dog, look down at the GPS, and find the other dog still on point 200 yards away. I call the youngster, and we head toward the old girl. As we get closer, a family group of grouse jumps from the ground, birds flying in all directions, and I shoot a young bird trailing the flock. This time, there is no hesitation from the young dog: He pounces on the bird before his companion can get there and promptly delivers it to me.

By this time, the sun is higher in the sky and the warmth tells me that it’s time to call it a day. I have enough water to get us back to the truck, but I don’t want the dogs to overheat. We sit in the shade of a large fir tree, the dogs panting and me reflecting on a near-perfect opening day. It’s almost like Christmas morning.

As a child, I loved Christmas and the anticipation of presents under the tree and surprise gifts that made the morning special. Of course, there were those contrary mornings as well, disappointment at not getting that special toy and wondering about just how many pairs of socks you really needed for the coming year. Forest grouse hunting can be a lot like that. Some years you climb to a favored haunt, and the birds seem to be everywhere, while other years, you may hunt your favored locations and never see a thing. Weather, nesting conditions, rearing habitat, and a variety of other factors lend grouse hunting an air of uncertainty and that keeps me hunting year after year.

I realize that today was one of my best openers, hunting two dogs that I love and doing something that I look forward to all year. As I look down at my four-legged companions, I realize that they are the reason I’m here. Their love of the hunt, the joy that they bring me, and the fruits of their labor make hunting a special season for me. It’s Christmas morning for this grouse hunter, and they’ve given me the best gift of the year.

Jeff Kershner is a former biologist who now spends his spare time writing about dog training and the outdoors. He and his wife, Nancy, live in southwest Montana, where they raise and train Braque Francais hunting dogs, one of the oldest hunting dog breeds in the world.

Bob White is an artist and author whose work expresses a misspent youth. Instead of doing his homework, his nose was constantly in the outdoor books and sporting magazines of the day. Consequently, he has wandered between Alaska and Patagonia for over three decades as an itinerant fishing guide looking for gainful employment. He now paints and writes for a living; which is to say, he’s still searching.

No Comments