23 Jul Opera in Montana: An Overture

FORGET ABOUT THE STIFF, WOODEN SEATS for just a moment and it’s easy to get lost in the lyrical voices filling the room, mingling with heart-thumping percussion, crashing cymbals and vibrating strings … oh the strings. With closed eyes and a full heart, you could be anywhere and everywhere the music will take you. In Verona, beneath Juliette’s balcony. In Nagasaki and Butterfly’s petal-strewn chamber. Or amidst the gaiety of Violetta Valéry’s Paris salon. But this opera, this indescribable splendor, finds you at the edge of that uncomfortable seat in an old high school auditorium in the middle of Montana. Go figure.

On the one hand, it is staggering to be in this rickety auditorium listening to singers who have, and will continue to grace the hallowed stage of New York City’s Metropolitan Opera. And yet, when you hear the story of Intermountain Opera Bozeman, how it came to be, and the way in which it continues to bring world-class opera to sell-out crowds in Bozeman, you begin to realize that maybe … just maybe … this couldn’t have happened in any other place.

It was 1978 when Verity Bostick, a young singer and assistant music professor at Montana State University, had a dream to bring opera to this small but verdant valley in southwest Montana. She managed to entice Anthony Stivanello, a well-known New York opera producer, into donating sets, costumes and his own talent as a director, for a fully-staged production of Verdi’s La Traviata in 1979. As she schemed, Bostick serendipitously learned of a recent transplant to the area. One Pablo Elvira, a world-famous baritone from Puerto Rico who, since 1974, had regularly starred in productions at both The Met and New York City Opera alongside such greats as Luciano Pavarotti and Placido Domingo. Elvira married Bozeman native Signe Landoe in 1975 and the couple made Bozeman their primary home. The singer was known to refer to his chosen home as “my beautiful state of Montana” and considered it something of a sanctuary, but he eagerly accepted Bostick’s invitation to sing the role of Germont when she asked. And with that, opera really came to Bozeman.

From there, the bar was set higher and higher by Elvira, as the artistic director of the burgeoning company, and a cadre of dedicated volunteers. In 1980, Elvira reprised in Bozeman what was perhaps his most famous role, and one that he had played to sold-out crowds the world over: Figaro in The Barber of Seville. With him were three other New York opera stars that he brought to the humble stage of what was once Gallatin High School, the same place where Gary Cooper graduated in 1922.

Over the years, Elvira brought his friends to Bozeman to sing, and discovered young talent both locally and afar. In addition to opera performers, Intermountain Opera Bozeman (IOB) brought in well-known stage directors and notable opera conductors from across the globe. Meanwhile, under Elvira’s watch, local singers formed impressive choruses for each production and the region’s best musicians made up the orchestra. The music school at Montana State University played a pivotal role from the beginning.

Linda Curtis, who sang with Elvira and succeeded him as Intermountain Opera Bozeman’s artistic director in 1996, recalled the mayhem of the early years. “Pablo would invite a few friends to come out and stay with him,” she explained. With the local chorus and all-star cast, the company would spend a week blocking (staging) the production at Elvira’s house. Occasionally, Curtis laughs now, the fun got the better of them. “The tenor in Il Trovatore was a dear friend of Pablo’s,” she said, alluding to nights with plenty of imbibing. “The night before the dress rehearsal, Pablo called and said ‘We’re getting a new tenor.’” Indeed, the new singer arrived the next day and sang from the wings, watching as the outgoing performer did the blocking on stage. It was fast and furious, Curtis recollected, fueled by passion and talent.

The contrast of that talent, both on stage and in the orchestra pit, up against the 1,100-seat venue and the impossibly short rehearsal schedule set the standard and established a vision that burns even brighter nearly three and a half decades later.

“The product that we create can stand up against a lot of larger companies with a lot bigger budgets,” explains Curtis, who travels several times a year to scout talent and uses her own experience as a soprano to anticipate the chemistry — both musically and theatrically — between singers. With an operating budget well shy of the $500,000 mark, Curtis puts together her “dream teams” of singers, stage directors and conductors for productions that are chosen according to audience appeal, budget considerations and Curtis’ own list of favorites. The spring production this year, Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, cast eight national performers who, between them, have performed on some of the most prestigious stages in the world, in addition to four local operatic singers, 25 chorus members, 30 orchestra musicians, five supers (silent actors) including a local first-grader, a renowned stage director and a rising star conductor. It was the organization’s largest production ever and, by all estimates, a rousing success.

“Last weekend, nearly 3,000 people attended three performances of Roméo et Juliette,” offered Jackie Vick, IOB’s executive director, a few days after the grueling production wrapped. “This is an astounding figure considering that that is nearly 10 percent of the community, or close to 4 percent of the valley’s population,” she marveled. “These figures are reflected in the Bozeman Symphony’s attendance as well, showing amazing arts support. Nowhere else in the nation can say they have that kind of support for audience participation,” Vick said.

This is a town that loves its opera and has managed to sustain it unlike other Montana companies. Montana Lyric Opera in Missoula is now defunct and the Rimrock Opera in Billings, which was also aided by Elvira in the late 1990s, has recently, according to Curtis, been absorbed by a theatre company. “We are unique in the industry,” she said.

Unlike some of the state’s other well-known arts organizations, including Montana Shakespeare in the Parks and Missoula Children’s Theater, IOB does not travel. The professional casts for each production come together from across the United States and often Europe, rehearse like mad for just under two weeks, give three performances over the course of five days, and then — just two and a half weeks after their first sing-through — scatter to the wind and whatever stage is calling. The local performers, singers and musicians take a deep breath before they start learning the next opera for the next whirlwind production.

Maestro Joe Mechavich, who conducted IOB for the first time with Roméo et Juliette, is used to working with high-caliber performers. What surprised him was the local talent. “The visiting artists at IOB productions are the very same artists you would see in opera houses around the globe. But the joy for me was to experience the high level of professionalism and passion demonstrated by the members of the IOB chorus and orchestra who are pulled from the Gallatin Valley,” he said.

Vick, herself a musician and music teacher, surmises that Bozeman attracts artists and art lovers with the intellectual environment at Montana State University and the strong arts community that’s grown up in town. “Bozeman is truly an incredible arts hub,” she said. In agreement, Curtis passed on a comment made over dinner with stage director Jeffrey Buchman and Maestro Mechavich. “They both said, ‘You guys have a gem of a location here. You could be Santa Fe North. You could be Aspen in Montana,’” both of which refer to communities with renowned summer opera festivals. “It’s good to have those dreams,” Curtis added. The two women couldn’t help but laugh as they explained that the reason IOB never offered summer productions is because all of the locals — needed to fill the chorus, the orchestra pit and the audience — are out hiking, camping and enjoying the great outdoors. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the fall and spring productions happen in October and May, between ski season and summer season. This is, after all, Bozeman, Montana.

So how do they pull it off season after season with such a limited budget and a venue that literally has the chorus dressing in the old shower room and playing Frisbee in the gym between scenes? “Opera family spirit,” Curtis said plainly. It means relying heartily on volunteers and patrons. It means getting out into schools in the area to build a young audience. It means staging an “It-ain’t-over-til-the-FIT-lady sings” 10-mile race in the fall, as much a “friend-raiser” as a fund-raiser, to keep tickets affordable for Bozemanites and make up for the 60 percent of operating costs that are not covered by ticket sales. It means rehearsing on a fast and furious time schedule. It means that everyone has to be willing to do whatever it takes to ensure that the show will always go on.

Season after season, the performers — many of whom form tight friendships that encourage them to come back for encore performances — respond to Curtis’ vision, the one that survived and flourished even after Elvira’s sad passing in 2000. “If you’re true to opera and you try to make it dramatically entertaining and vocally inspiring, you can’t just ‘park and honk,’” Curtis said with a lighthearted reference to operatic singers of a bygone era who stood center stage and simply belted it out instead of really performing the opera.

Singer Sean Anderson, an accomplished baritone who has performed with Santa Fe Opera, the New York City Opera and dozens of others, sang the role of Mercutio in Roméo et Juliette, his third IOB production. For him, the combination of the pay, which he calls “reasonably competitive,” combined with the freedom to work into difficult roles without critical scrutiny and, surprisingly, the breakneck pace, were factors that made his yes an easy one. “Four weeks is pretty standard for regional companies. At IOB, the entire production, including travel to and from Bozeman is completed within two and a half weeks. While this makes for a very hectic rehearsal process, the IOB’s tradition of hiring high-level professional artists results in quality productions … ,” he offered.

Tenor Brian Jagde, another rising star on the world opera stage, played the role of Pinkerton in IOB’s spring 2012 production of Madama Butterfly. He admits that despite the company’s size — “IOB is definitely on the smaller side of tiny on the map of opera,” he said — the experience was a meaningful one. “I think being in Bozeman surprised me with all the things I gained from the visit. I met some great people,” he said. “And I got to see a part of the country I’ve never been to.” Since his Bozeman performances, Jagde headlined the Santa Fe Opera, the San Francisco Opera and won second place at the 2012 Operalia Competition with Placido Domingo. His 2013 schedule includes performances in Prague, Limoges and at the Minneapolis Opera. His 2014 schedule already includes a run at New York’s Met. Still, said Jagde, being on a flight to Bozeman was the first time he was ever recognized by other passengers as an “opera star.” It’s an encounter he reflects on fondly, and one that says a lot about this small mountain town.

So whether IOB will turn into something bigger and flashier, or whether the company will simply continue sharing the joy of high-quality opera to the thousands of devotees in Bozeman, Montana, remains to be seen. Sean Anderson, for one, doesn’t have to stretch to see the possibilities. “At IOB there is a flicker of a spark sitting on a huge powder keg of potential. It’s exciting to be a part of something like that. I can see myself as an old man saying to young singers, ‘I performed with this company back when all they had was an old high-school auditorium.”

- The antiquated gym at Willson School provides the chorus’ dressing room and backstage area, where performers often play Frisbee between scenes. Here Melina Pyron, who played Stefano in Roméo et Juliette, practices her aria and swordplay. | Photo by Carter Walker

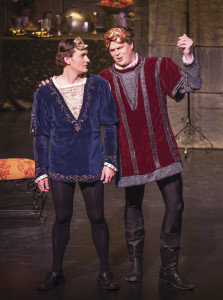

- Roméo (left), played by tenor Glenn Seven Allen, sang in his second IOB production just a few weeks after his Carnegie Hall debut. Baritone Sean Anderson (right) sang the role of Mercutio in his third IOB production. | Photo by Bruce Jodar: Wildeye Photography and Rufus Cone

- Soprano Cynthia Clayton and Tenor Brian Jagde brought Butterfly and Pinkerton to life in IOB’s 2012 production of Madama Butterfly. Siri Saeteren, a local kindergartener at the time, played the role of “Trouble,” the couple’s love child. | Photo by Bruce Jodar: Wildeye Photography and Rufus Cone

- Mezzo-soprano Cindy Sadler played the role of Gertrude, Juliette’s nurse. The child, played by Siri Saeteren, now a first-grader, represented innocence throughout Roméo et Juliette. | Photo by Bruce Jodar: Wildeye Photography and Rufus Cone

- Following the deaths of Mercutio and Tybalt in a climactic scene from Roméo et Juliette, the entire cast is onstage as The Duke (sung by Phillip Judge, center, in red) banishes Roméo forever. This cast, numbering 42, was the largest ever for an IOB production. | Photo by Bruce Jodar: Wildeye Photography and Rufus Cone

- Shown here in a 1982 Met production of Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, Pablo Elvira was perhaps best known for his marvelous comedic portrayal of Figaro. It was the same role he played in 1990 in his final Met performance. | Photo by Winnie Klotz, courtesy the Metropolitan Opera Archives

- Acclaimed stage director Jeffrey Buchman addresses the chorus before opening night. The exquisite IOB costumes are still provided by the Stivanello Costume Company, 35 years after their first collaboration. | Photo by Carter G. Walker

No Comments