20 Aug Artist of the West: New Directions: Shawna Moore

THE SCENT OF HONEY, a blossom of paint, the heady buzz of heat.

Stepping into Shawna Moore’s 1940s bungalow in Whitefish, Montana, the afternoon light slants across the studio. Here, Moore works with wax and paint, razors and fire, scraping back layers and gouging impressions into the still soft material.

Her newest body of encaustic work leans in cushioned stacks against the walls, waiting for one more pass, a final signal of completion. In this series, most delineate a horizon line, sky and land, weather and water, but they are not pictorial; rather they invoke the duality of atmosphere.

Moore melts a brick of wax, the source of the sweet perfume, turning on a series of exhaust fans. She lays a thin, wide brush in the umber-colored liquid, moving the wax until it disappears. Picking up a propane torch she holds the blue flame to her painting, exciting the molecules so they accept the new layer. The hot flare dances to the shush of the fire. In the wake of intense heating, the surface glimmers and for a moment anything can happen.

“Sometimes when I work in a series I know where I’m headed,” Moore says, shutting off the propane torch and reaching for her thin, thin brush. “New directions start with a basic concept or color but evolve organically. I usually set the color and then I start working.”

Nearly finished, the piece is rich ochre, gridded with dark brown clouds. Tiny drops of black ink look like an accident, but feel intentional. From beneath the lightest part of the painting a kind of translucency opals up, like a moonstone, illuminated by the bounce of natural light — a brightness that seems to come from within the piece itself.

“It really needs another layer, but I don’t want it to mute what I have here,” she says, picking up an Exacto knife, scraping at a small area. “Every mark is a synthesis of me — what I like — it’s as if I’m saying, ‘here’s a day,’ and then I seal it in.”

Like looking back at an archeological site, her work tells the tale of her emotions and thoughts at a particular time. It may be hammered bike chains or rolled gears across a white expanse. It may be hurled arcs or miniscule abrasions that scratch at our souls like reminders. As her marks reveal, not only reactions but the colors underneath, her work feels vulnerable and at the same time strong. It may be because of her ultra-smooth finishes that act as a kind of armor.

“I’m looking for a visual texture,” she says. “It might look like bark, sandstone, leather. And then I start concentrating on getting my wax smooth. It’s like I want to find out how much damage I can inflict on my paintings and then get it to be perfectly smooth.”

Leaving her piece to sit, she moves a few steps to stand in front of a piece based on a small ceramic pot her mother gave her, one she’d seen around her childhood home. “It’s what that pot would look like if it were a painting,” she says, holding the small vessel in her hand and then placing it on a stool in front of the painting, Three-Fold Sky. The granular ridges of raw clay and the cerulean glaze lend themselves to the language of wax.

“It’s the mingling of the mind, heart and spirit,” she says, running her hand over the pot. “Or it could mean outer, inner, deeper.”

As she speaks of her beginnings, starting out as an architecture student and then discovering painting and finally wax, her voice has the quality of a rhythm, the quiet tones of meditation. And it becomes easy to see her work as an extension of who she is, the two disciplines of life and art like breathing — in and out — tied together.

One of her early encaustic teachers, artist Ellen Koment, first met Moore during a workshop about 10 years ago.

“As soon as she started I knew she was a good painter,” Koment says. “I’ve watched her work change over the years: She’s become very specific, it comes out of her own life; she really uses wax as a ground she can build on.”

Last year Koment and Moore conducted a workshop together, bringing their relationship full circle.

“It was interesting to see how she builds up very thin layers with a shift between them, it’s very intentional, rather than emotional,” she says. “Her layers are very fine so you’re seeing through them — which is the beauty of transparent layers. She has a different approach than I do — there’s a tonality to her work. Her virtual texture, which is very smooth, allows you to see through the depth where the marks are suspended, hand painted or inscribed.”

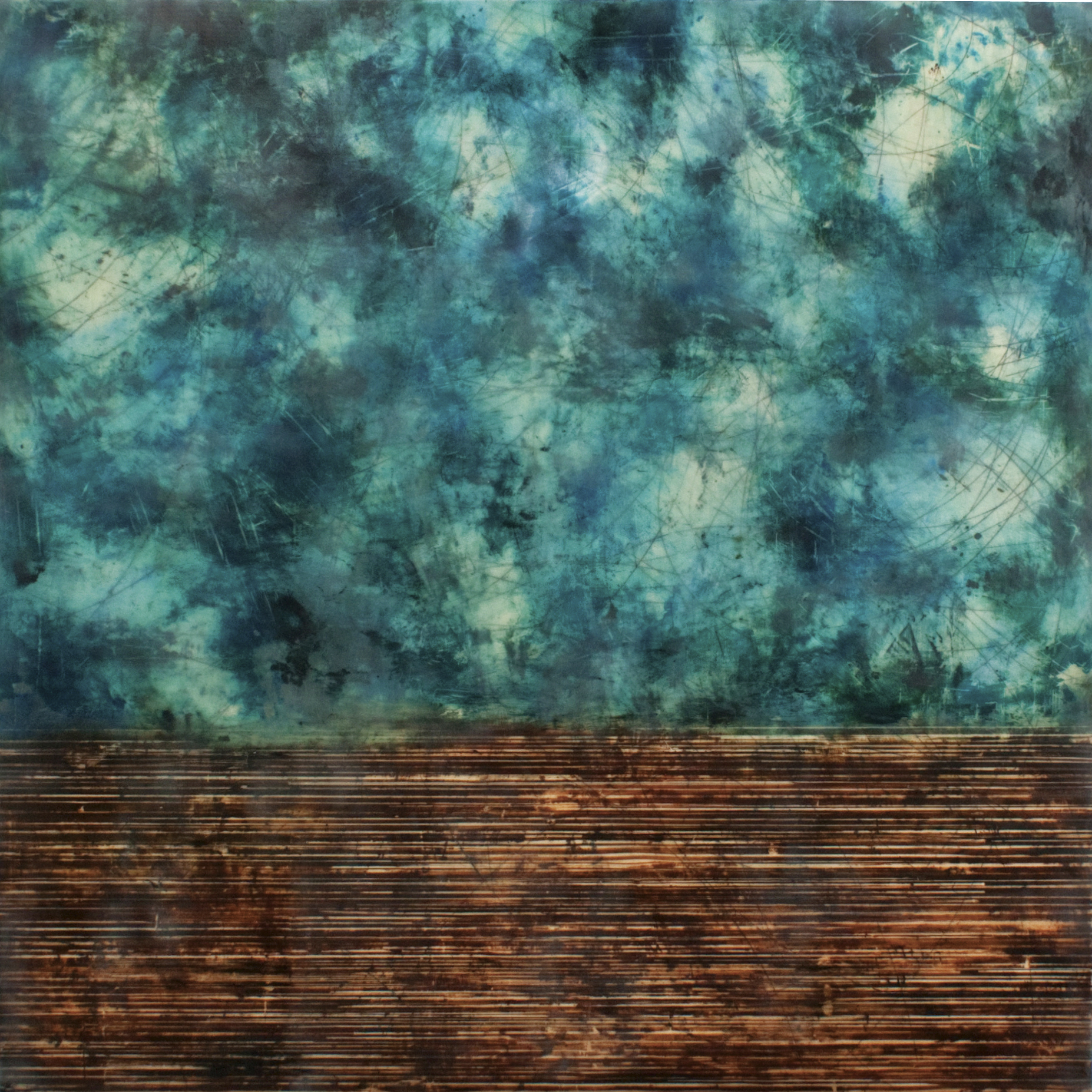

In Moore’s newer piece, Sky Map, there is the clearly delineated split of sky and land. The land stretches across the surface in striations, barely masking the depth of earth and soil, creating a rolling rhythm of working the land. The sky moves and undulates, darkness mixed with blues, like a storm rumbling so loudly you almost step away from it. A contained movement embedded with anticipation, maybe even a little fear in the lines and gouges filled with ink and covered with wax, suspended in the moment.

“I think of these divided pieces as maps,” Moore says. “Holding with the idea of elements.”

As her work progresses from “color field paintings with marks,” as she calls them, to images more indicative of landscapes, to pieces that move around the idea of water, of sky, of earth, all the while she is taking note of the process.

This is something Julie Gustafson, who represents Moore’s work at the Gallatin River Gallery in Big Sky, is acutely aware of. Gustafson feels Moore is truly a master at working with encaustics.

“She has a great way of looking at her life as an artist,” Gustafson says. “And that comes through in her work. Her paintings really draw you in … and then you see all the layers. And the encaustic medium is just gorgeous. I think she’s doing some really great work, introducing some calligraphic markings, which gives them an exotic feel.”

Back in the studio, as the light begins to wane, Moore shuts off the skillet and lays her brush down. Her paintings, like students, are lined up and ready to go. Setting off to Park City, Utah, for a show, Moore thinks about her series work, the road that got her here and the next creative challenge.

It is this yearning for challenge, to speak in the words of color, to convey her breath through layers of thin, thin wax that we come away with not just the feeling of having seen Moore’s work, but of experiencing it fully.

- The painting “Three-Fold Sky” is based on a small ceramic pot given to Moore by her mother.

- “Red Blanket” | Encausitc on Panel | 60 x 40 inches

- “Sky Map” | Encausitc on Panel | 40 x 40 inches

- The painting “Three-Fold Sky” is based on a small ceramic pot given to Moore by her mother.

- “Central Axis” | Encaustic on Panel | 40 x 60 inches

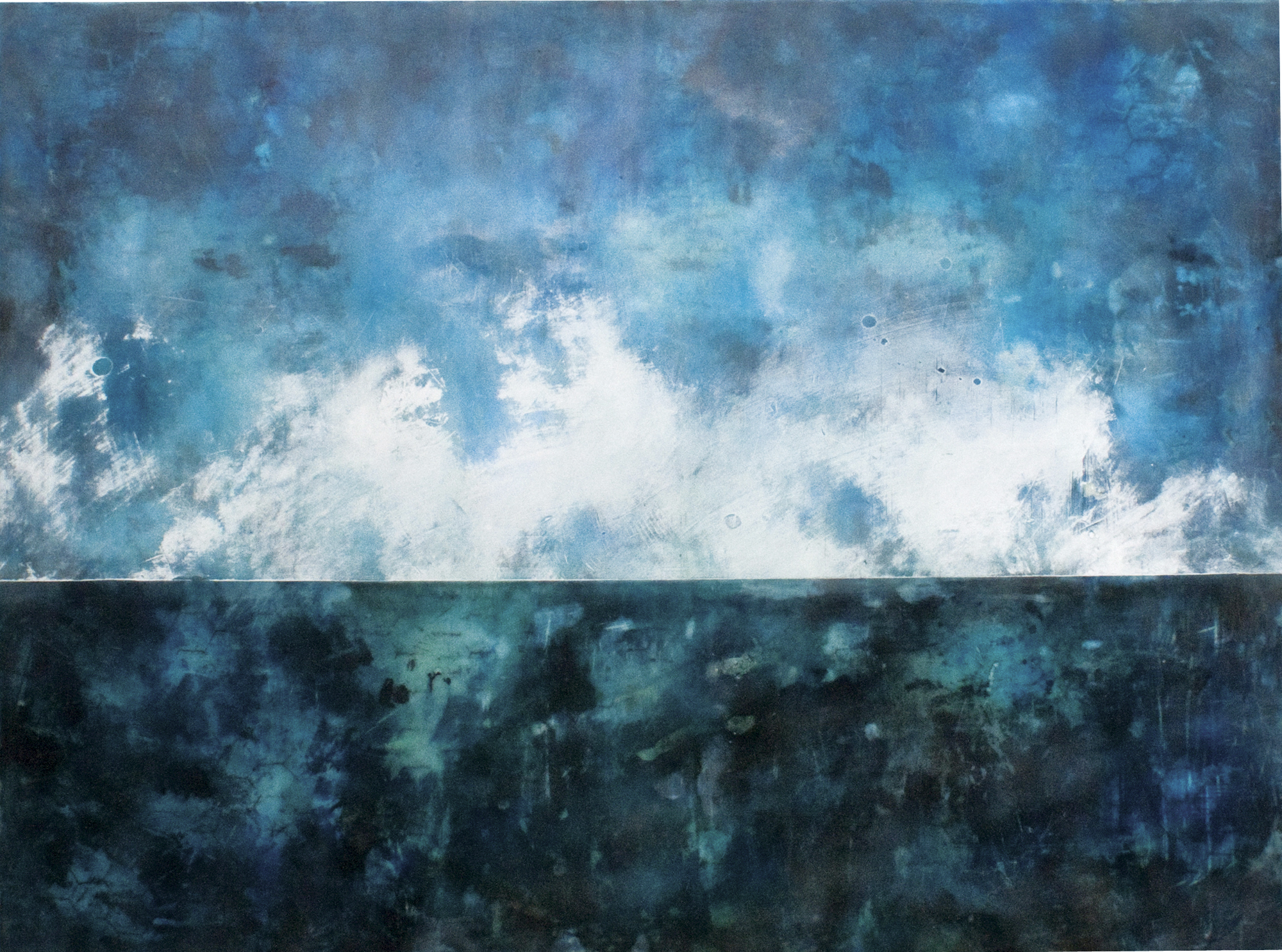

- “Troubled Water” | Encaustic on Panel | 30 x 40 inches

- Worn tools of the trade.

- Shawna Moore applies heat to her work in progress at her Whitefish studio.

No Comments