01 Sep Artist of the West: Natural Impressions

“Art is an experience, not an object.”

— Robert Motherwell

WHEN SCULPTOR GEORGE BUMANN PULLS DOWN the dark shade in his small studio, a mile or so outside of Gardiner, Montana, he opens himself up to the wilderness in which he works, lives and breathes. He knows his surroundings intimately, feeling his way through the clay, as if by heart.

Living in the sagebrush and bare rocky soil are the subjects Bumann studies: the last wolf in a dying pack, a neighbor’s ewe, the delicate legs of a 2-ton bison. With a master’s degree in wildlife ecology, Bumann understands the animals on a deeper level than most. It is from this understanding, this innate knowing, that he is able to communicate a language of survival, strife and unobstructed beauty.

Because of his proximity to Yellowstone National Park, Bumann can “watch elk ears or noses for a day,” he says. “Maybe I’ll see a buffalo being born, two wolf packs collide, or a grizzly bear mother with her cubs. Just by being there, I’m building my inner knowledge. There is so much here for art to celebrate — things can fade in your memory so easily — and art is the means of exercising the muscle of understanding. I want to remember the moment that stops you cold.”

To understand the depth at which Bumann studies his subjects, he will spend a whole day with one animal — if he can — to see how the ears stand or the muscles in the neck move with each new situation.

His sculpture, Endurance, is an emotional portrait of the last wolf in the Druid Peak pack.

“It came from the ability to follow an individual around for five years,” he says. “To internalize it. It became a real relationship.”

That pack was reduced from 37 to four before Bumann’s eyes.

“They all had mange,” he says. “They couldn’t lie down in the snow because they were so cold, so they’d huddle together. It was gut-wrenching to watch.”

All of the Druid Peak pack is gone now.

Except for the small bronze piece that Bumann holds in the palm of his hand. Only 5 inches long, single pads of clay make up its coat, hanging onto the bones like a gasp, head bent, ears forward, tail down. With gouging haunches, Bumann’s fingerprints impart a piece of himself onto the wolf — the piece he lost watching the pack die.

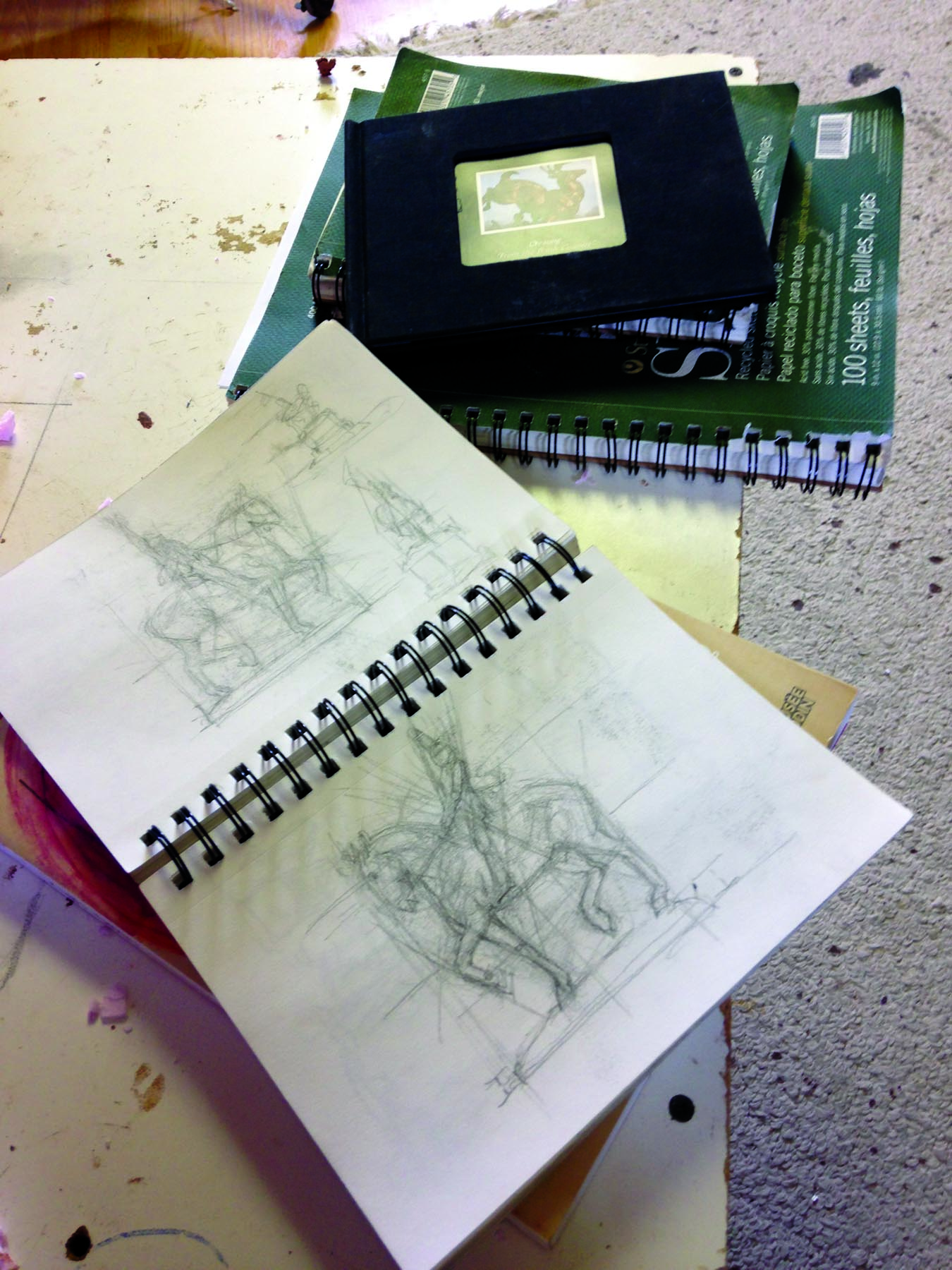

He opens an overhead cabinet to reveal dozens of miniature wolves, elk, bison and moose. These are his sketches, like painters keep on the wall, although Bumann does have some of those as well.

“I come back to these studies to see if they hold up,” he says. “Some ideas need to gestate.”

Like the 22-inch bronze of the bull moose he pulls out from beneath a cloth.

“One day I was in the Tetons with a bull moose, his lady and a calf, when another bull came up,” he says. “That bull moose ran him off, I tried to follow him for bit.”

Bumann waited until he returned, one-and-a-half-hours later.

“You see that coiled spring, those ears, up and pointed, the tautness in his back and the gorgeous serpentine line of his spine,” he says. “I know the musculature but I also need to know what it was that made me stop at that moment to look at the bull. That tension of knowing he only has two weeks a year to further the species.”

Bumann does that by not replicating the wildlife he sculpts, but instead getting just the right distortion to portray a certain state of grace.

“I’m concerned about the edges, where the light reacts with the surface,” he says. By using such tools as a jagged-tooth dry wall knife or a piece of firewood with just the right face and curl, Bumann can play with the skin of the sculpture. “I’ll try to enhance certain aspects to work with the light.”

Meredith Plesko, owner of Insight Gallery in Fredericksburg, Texas, represents Bumann’s work.

“I think what drew us to George’s work was his fresh approach, which is more impressionistic,” Plesko says. “You understand that he has this vast knowledge of the animals but then he adds his artistic vision to it. His work is well-rooted in anatomy but he gives it his own take.”

Plesko commented that although her collectors live in Texas, and don’t see the wildlife Bumann sculpts, they’re still attracted to his work.

“Collectors have really responded to his sculpture,” she says. “People are drawn to his work because they appreciate his approach and … the quality it represents. Quality always sells. Trends, fads, you can’t go with that. The basic elements of sculpture, that’s what wins out in the long run.”

Bumann was recommended to Plesko through another artist, which is the way she likes to find new artists. Due to the size of her gallery, Plesko has to be careful about who she represents, while still keeping the gallery relevant.

“Our gallery is relatively smaller than some of our competitors, but it allows us to represent individual artists well,” she says. “We weren’t looking to add an artist. But George’s work was exceptional and we couldn’t not have it.”

Bumann comes to sculpture easily. His mother is a sculptor and he grew up in her studio, watching her work and helping her with installations.

At the same time, he’s always been interested in nature. When it came time to go to school, he came away with a master’s degree in wildlife ecology. Then he began working full time for the Yellowstone Association as an instructor and a guide.

“But it was a segue to a desk job,” he says. “Yellowstone ended up being the perfect place for me. It kept me out there, seeing things most people don’t see.”

It wasn’t until his father got cancer and he had to help his mother with her sculptures so she could get back home, that Bumann discovered his path.

“After that experience I saw sculpture was a tool I had and it started to make sense,” he says. “I had to ask myself, ‘What am I supposed to be doing?’ Sculpture married two worlds for me and I’m so thankful it did. Each discipline feeds and builds on the other.”

Jeffrey Schutz, Montana collector of 20th- and 21st-century American art, has three large sculptures and one small study by Bumann.

“George has an incredible knowledge base, being a naturalist,” Schutz says. “He really understands the natural world and the anatomy of the subjects he sculpts. But more than that, he can capture the animal’s presence in their environment. It’s really quite impressive, especially that he can capture it in bronze.”

Bringing Bumann’s work into his collection was a very conscious decision.

“As a collector, I have a reasonable eye for young emerging talent and I like to add those artists to our collection before I can no longer afford their work,” Schutz says. “He really is a great American Western sculptor.”

In his studio, Bumann starts with a simple armature — a pipe fitted with thick, malleable aluminum wires — to build his piece. Reaching into his warming box for two handfuls of reddish brown clay, the same clay once made for the auto industry, he begins to add form to the structure. The oily odor rises in the room as Bumann applies the medium.

He talks as he works, but his hands move so fast it is as if the information in his head is coursing through his fingers.

“A musician has chords to express himself,” he says, barely leaving a second before the form in front of him changes again. “A sculptor has clay and wire. How do I make it speak? What is the syntax I want?”

A quick press of clay anchors two wires to the ground. Back legs.

“Art is an experience of our surroundings,” he says, adding more clay to ground the forelegs. “The head of a wolf is as long as its neck. But just getting the data is the reason I left science.”

More clay is molded in his grip. “Alphas carry their tails up.” He moves the clay-covered, wire tail to show the difference between a straight tail and one lowered. It changes everything.

Bumann gets up from his sculpting chair, which puts him at eye level with the piece, and walks to his shelves. He pulls out a thick, thick file, opening it at random.

“I have a road kill kit,” he says, riffling through the paperwork. The kit has data sheets, knives, calipers and other instruments for measuring. “Every time I find something, I can gather a ton of information.”

The data form lists species, date, place, sex, size basics and then his sketches.

“What this does for me is it guarantees I’ve had my hands on this animal 96 different ways. It puts a physical map in my head.”

He goes back to the clay and presses, pushes and feels his way around.

He works rapidly, accessing every wolf he’s ever encountered, and at the same time channeling the authenticity of a particular wolf.

Bumann speaks through his hands, using his heart to absorb the wild, soundless cries, the brittle whimpers and fearless observations, to ultimately convey the intangible: hardship, strength and an emotional truth.

- George Bumann sculpting bison from life in Yellowstone Park’s Lamar Valley.

No Comments