20 Aug Images of the West: Montana’s Original Man Camps

LONG BEFORE THE BAKKEN OIL FILEDS MADE THE TERM “MAN CAMPS” FASHIONABLE, there were similar encampments all over western Montana. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the lumber industry spawned such camps in nearly all of the valleys and drainages to supply raw timber to the burgeoning mining and railroad industries. There were similarities with today’s oil patch residences, but there were stark contrasts as well.

Montana’s earliest communities started as “timber towns,” built almost exclusively of rough sawn lumber and logs from nearby mills. Owing to the sheer abundance of timber stands, wood was the most common and desirable building material. Thus, throughout Montana’s early territorial period and into the 20th century, its scattered communities relied on nearby timber supplies to construct homes and businesses.

By the latter part of the territorial period, Montana began to turn the corner with its architecture when swelling populations, massive wealth for a few, and a certain air of Gilded Age opulence altered building styles from log shanties to granite, brick and stone structures. Additionally, sweeping structural fires frequently gutted vulnerable wooden towns causing city officials to issue decrees requiring more durable, fire-resistant buildings. Still, mines and railroads continued with their demands on the state’s vast timber resources and rapacious logging companies were only too eager to respond. Timber poaching and overcutting were common practices.

Along with industrialism came the growing need for raw timber to fuel the huge copper mines and smelting facilities in Anaconda and Butte. Below ground, miners needed huge timbers to shore up drifts and tunnels. Above ground, railroad workers needed large-dimension logs and milled timbers to erect trestles, bridges and to supply the persistent orders for rail ties. The answer to increased demand was increased output, on a massive scale, from outlying logging camps.

In a literary sense, life in logging camps has been with Montanans since Norman McLean’s release of A River Runs Through It in 1976, wherein the novella, “Logging and pimping and ‘your pal, Jim,’” describes the quintessential Bitterroot Valley lumber camp culture. Lying in his bunk one Sunday McLean listened to his fellow lumberman grouse about the Anaconda Company as they “ … registered their customary complaints about the “Company” — it owned them body and soul; it owned the state of Montana, the press, the preachers, etc.; grub was lousy and likewise the wages, which the Company took right back from them anyway by overpricing everything at the commissary, and they had to buy from the commissary, out in the woods where else could they buy.”

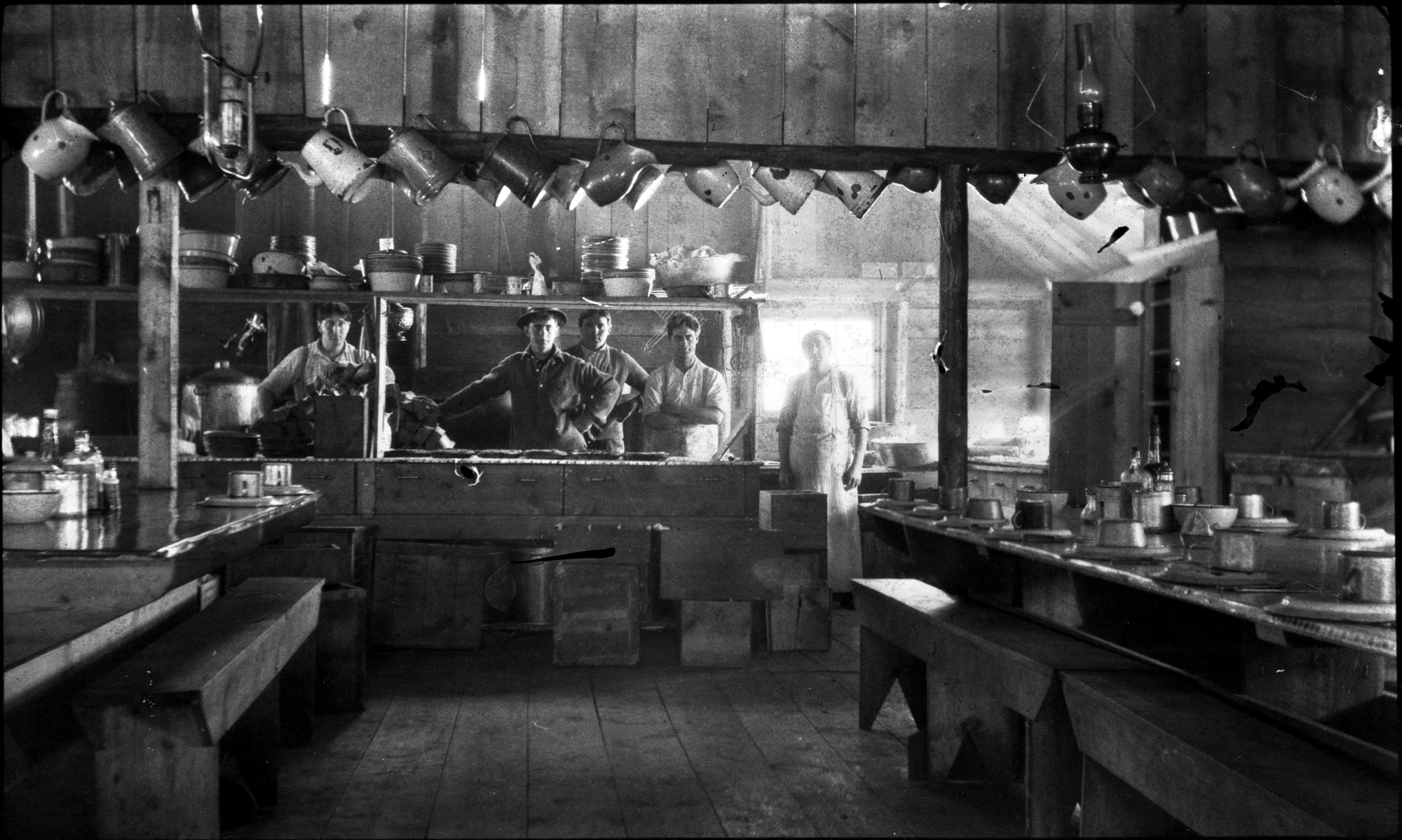

Typical man camps of the logging era followed a formula-driven template: a singular cook and dining building flanked by a superintendent’s home and office and several bunkhouses. Large camps might include a barn for draft stock, a company store, warehouse, commissary cold storage ice house and, if the lumberjacks were fortunate, a wash house.

Some variations might include facilities for winter logging, which was the norm throughout forests of Montana as the logs could be maneuvered more easily on snow. Logs needed to be cut and then skidded on chutes, flumes or hauled on sleds to nearby rivers and placed in holding ponds or rafts that would be released into the high-water runoff of spring. These gigantic “log runs” would send piles of cut timber down a drainage, scouring everything along the banks, to the nearest sawmill where they would be “yarded” and then turned into useful dimension lumber. These iconic log runs were one of the true hallmarks of the great lumbering era of Montana.

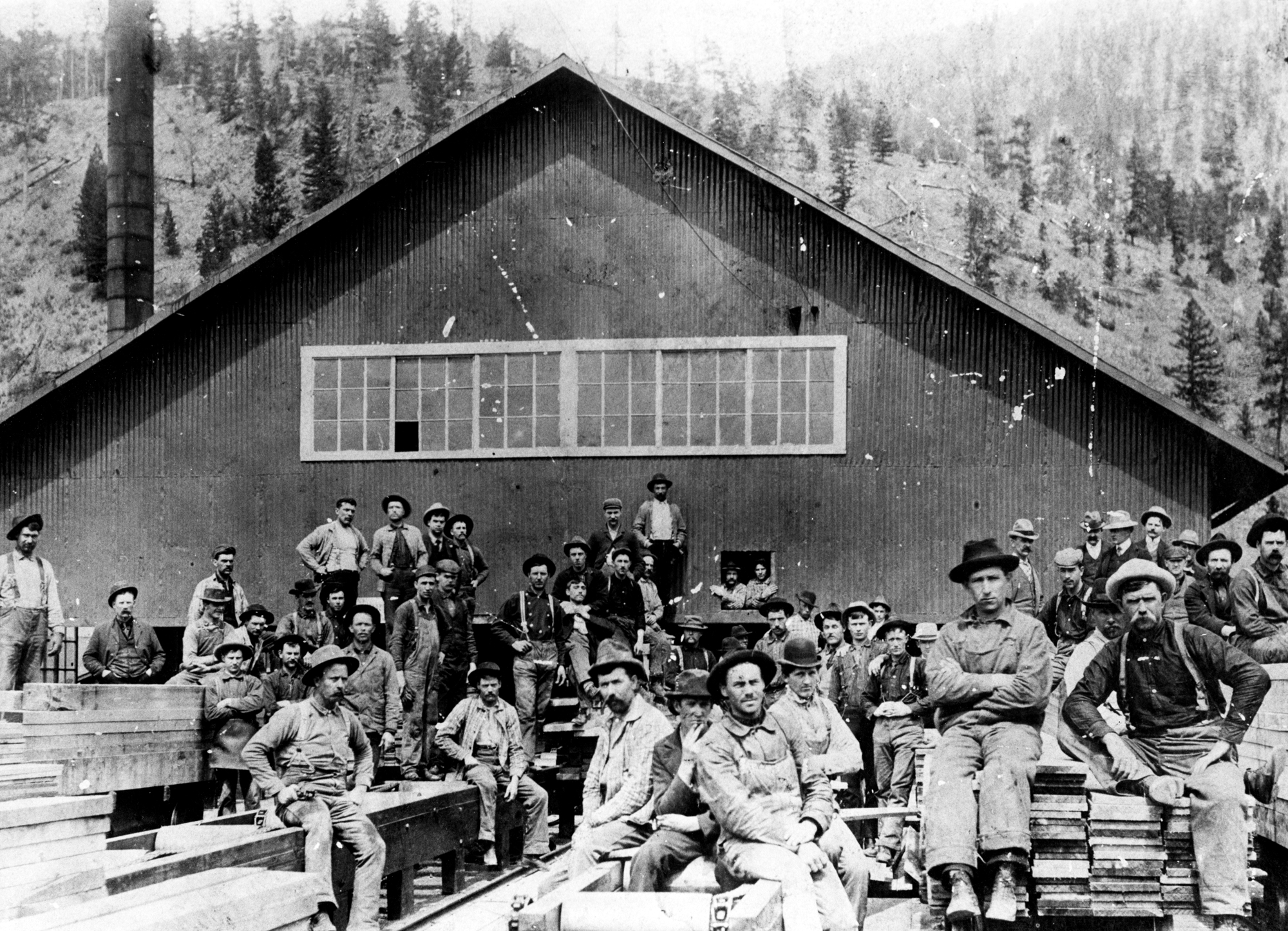

Such an effort required manpower of unimaginable scale. Large logging outfits would put on dozens of lumberjacks and camp support personnel and work them 12 hours per day, six days a week. If you couldn’t drag a two-man crosscut saw or swing an axe, there were jobs for saw filers, blacksmiths, farriers, harness makers, liverymen, cooks, hunters, railroad engineers and boilermen, bookkeepers and wranglers.

Camps hired men based on skills and availability. Much like today, most all men living in these early day man camps were itinerants and seasonal laborers. When a drainage had surrendered all of its suitable timber, camps would close altogether or move to another locale where new buildings, seldom more than temporary quarters, would be quickly erected. Lumberjacks followed the camps and the work and the seasons. They drifted individually and sometimes collectively from camp to camp, measuring pay and living conditions and owing scant allegiance to lumber company officials. Workers thought nothing of quitting a camp because the cook was a “belly robber,” who put out “poor doin’s” in the dining hall. Good relations with the paymaster and camp superintendent also determined whether the workforce would remain on the job through a cutting season. Those who stayed were obligated to the camp rules and, for personal purchases, to the company-owned camp store that charged items to the ’jacks’ pay vouchers. Life in these man camps was not intended to be comfortable. Women and alcohol were prohibited, although some of the “bull cooks” were women.

The most obvious differences between today’s man camps and those of 100 years ago are the advanced sanitary conditions in today’s camps, more efficient building materials and the more self-contained nature of the actual quarters. The truth is, modern work camps are chiefly individualized “man caves” on a broader scale. Bakken man camps feature largely independent living scenarios, whereas lumbering camps were communal. Today’s work camps feature Internet nodes, satellite dishes and computers. In addition, today’s man camp residents are more mobile; most employees own vehicles to get them to job sites, shopping and home towns, often far away. Logging camps, by contrast, required the employees to remain on site for weeks and months until the harvest period was complete.

Today, Bakken oil patch workers can purchase their own fifth-wheel and RV portable quarters specially designed for Montana’s harsh winters. Such luxury would have been unthinkable a century ago and certainly out of reach for loggers’ $2-a-day wage.

Logging camp buildings took many forms from boxcars and floating “wanigans,” to tents known as “rag camps.” Initial company crews on a harvest site would construct crude “tote” roads into a drainage for hauling supplies in and lumber out. Log structures were de rigueur. Some were portable frame shanties. Typical company crews — like the Anaconda Company work camp Norman McLean worked in on the Big Blackfoot River in 1927 — lived in cramped quarters for anywhere from 30 to 80 men. Darris Flanagan’s book, Skid Trails: Glory Days of Montana Logging, describes the living quarters as having a door on each end, one kerosene lamp and a double-barrel stove made from oil barrels. Bunkhouse walls were lined with two-story bunks with hay or straw mattresses. Eight-inch boards on either side kept the straw in. Each lumberjack supplied their own bedroll. The bunks were “muzzle loaded,” so close together that the men could only enter them from the front and crawl across to the head of the bed. Overhead were strings of number nine phone wire upon which were hung dozens of woolen underwear, socks and damp mackinaw coats for drying.

Not surprisingly, because of the unsanitary conditions, fleas and lice were everywhere. A classic story from one jack describes a time when he was awakened in the middle of the night by two bedbugs talking. The first one said “Shall we eat him here or drag him to the corner?” The second one said “Eat him here, if we drag him to the corner the big ones will take him away from us.” Other observations from camp employees noted sarcastically that the only time it was safe to go to the latrine was at mealtime when the flies were all in the cookhouse.

“Come Sunday,” one sawyer recollected about his years in a Swan Valley camp, “all the men would be naked on the streambank washing themselves and their laundry. If it was sunny, we’d hang the clothes on trees to dry, otherwise, we’d just string ’em up inside the bunkhouse and then stoke up the fires. That usually turned the bunkhouse into a big steambath. Afterward we would wrangle a team and wagons and go to town for tobacco and other such and then tie one on. It was a good thing the horse teams knew the way back to camp because we were in no condition to drive ’em.”

Well-managed camps raised a small garden in the summer, comprised mostly of potatoes, and pigs were raised for meat but also provided the additional service of consuming garbage. A meat house — a refrigerator-like screened structure to keep the flies out — perched over a nearby creek. Some camps had milk cows and chickens.

Next to the superintendent, the camp cooks were the most important personnel at the job site. “Good cook, good camp” was the oft-mentioned phrase by loggers, and they weren’t happy until they had both. A cook’s day began at 4:30 a.m. to get fires going and make coffee. “Flunkies” hauled water, cleared floors and dishes, split firewood and as many as three to six “bull cooks” cranked out hotcakes, eggs, bacon or sausage fried potatoes, oatmeal and cornflakes. Loggers were obliged to sit in silence except to ask for table utensils. The tables cleared and the loggers gone, cooks prepared lunch that was taken to the cutting areas by the flunkies on mules, livery vehicles or horse drawn wagons or sleds. There, they built fires to warm the food and then returned with the dishes to the cookhouse. After the evening meal, cooks labored into the night to cut meat, peel and boil potatoes and mix flapjack batter. Flunkies split firewood and set the tables again for the next day’s breakfast.

Today, scant physical evidence remains of these once busy encampments. McLean remembered “ … there was no such thing as a chain saw then, just as now there is no such thing as logging camps or a bunkhouse the whole length of the Blackfoot River. But in the days of the logging camp, the men worked mostly on two-man crosscut saws that were things of beauty … ”

- The Western Lumber Company dinkey hauled logs along the streetcar tracks to the landing upriver from the highway bridge, and on the west bank of the Blackfoot River. Photo from University of Montana Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library

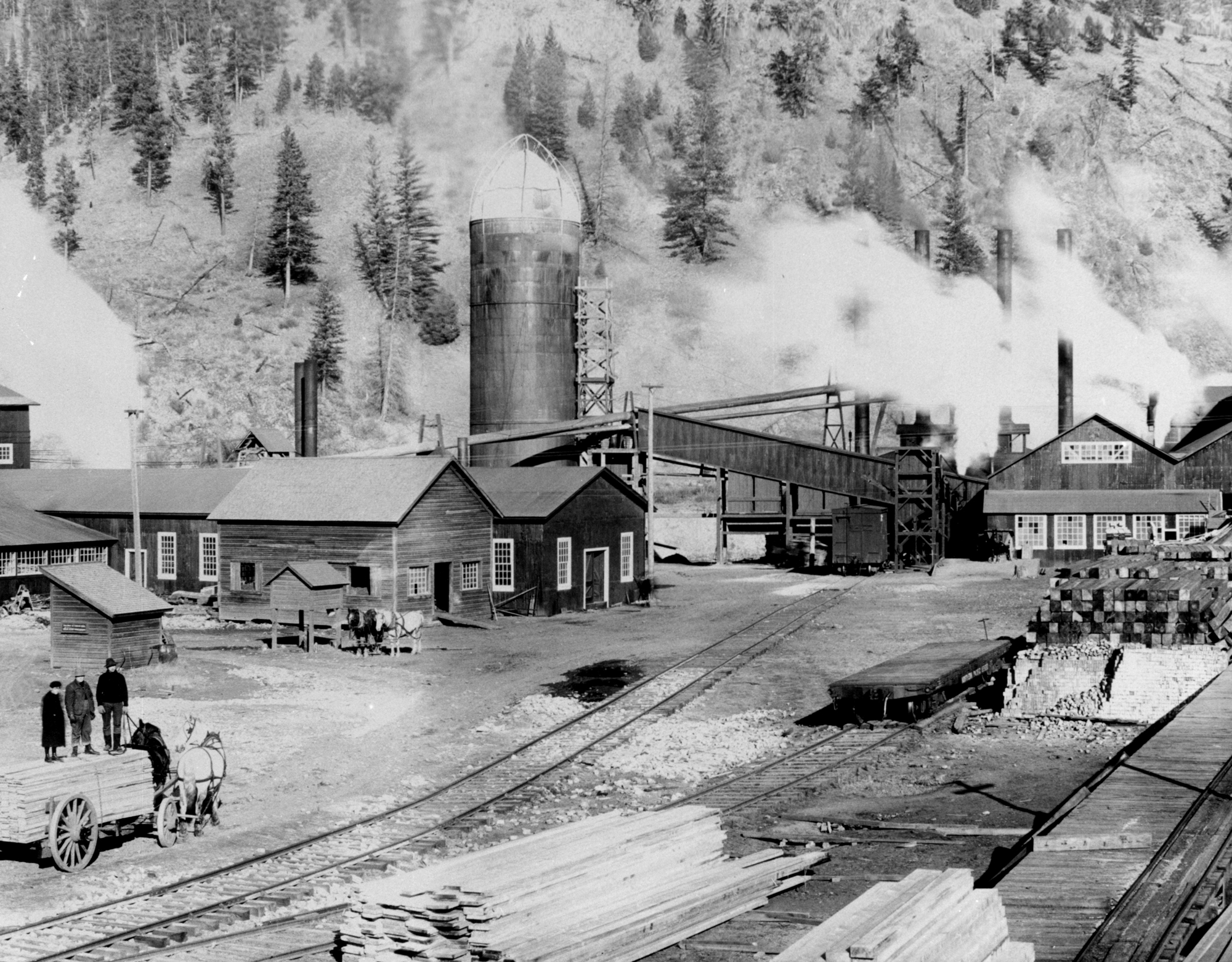

- Company town: The Old Bonner Mill was founded in 1885 in the Blackfoot Valley and remains in production again as of 2011. Photo from University of Montana Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library

- Dozens of workers sit or stand on lumber piles at the ACM Sawmill before 1908. Photo from University of Montana Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library

No Comments