03 Feb Montana’s Island Ranges

EVEN A THOUSAND VERTICAL FEET ABOVE the surrounding plains, July heat in northcentral Montana’s Bears Paw Mountains climbs into the 90s. My wife Mary and I drift flies through the riffles, runs and pools of crystalline Beaver Creek, south of Havre. But the furnace-blast afternoon makes the trout grumpy. So, we fluidly morph to Plan B like fly rod-wielding Zen masters: Mary slips into her bathing suit and cools down in the stream, while I daydream under a sheltering cottonwood sipping beer, pondering puffy cumulous clouds floating past the surrounding aspen- and ponderosa-clad ridges.

Mary and I feel like the dirtbag king and queen of our wild domain. We temporarily “own” a perfect, streamside campsite on beautiful Beaver Creek, threading through one of the nation’s largest county-owned parks. Visiting midweek, we have the stream and two trout-filled lakes nearly to ourselves. We could have fished the peak caddis hatch on the Missouri or Madison, but would have had to share it with crowds of anglers from across the country. Instead, we took a lesser traveled road — beyond the pages of most fly-fishing guide books — to explore one of Montana’s iconic island ranges, an ancient volcano that offers an outpost of quiet and solitude for vagabond anglers.

Forested Islands in a Sea of Grass

Pondering “island ranges,” one might picture the Hawaiian archipelago, verdant volcanic peaks rearing thousands of feet above the roiling Pacific. But in the Northern Plains, distant ship and whale-like escarpments rise through mirage-inducing heat waves, above an ocean of swirling prairie, pasture or wheat fields. The huge sky and long, curving horizon suggest a world without end.

Montana’s island ranges are separated from the massive chain of the Rocky Mountains and Continental Divide ranges — think Glacier National Park or the Bitterroot Mountains — by the undulating Great Plains and broad river valleys. These remote oases capture sufficient moisture and are cool enough to support creatures (like trout) that seem anomalous from the semi-arid plains below. They afforded Native Americans spiritual refuge and promontories for spotting bison herds; they provided wood, water and other materials for 19th century trappers, miners, homesteaders and westward pioneers. In his excellent book, The Mountain Ranges of Eastern Montana: Islands on the Prairie, Mark Meloy observes:

“These mountains were frontier signposts, landmarks that suddenly gave dimension, relief and a sense of destination to the seemingly interminable horizon. Their distinctiveness evoked a sense of imminent change, an anticipation of new landscapes and a premonition of the great land barrier, the Rocky Mountains.”

Famously immortalized in paintings by artist Charlie Russell, the sparsely-populated island ranges and buttes encompass a different, nearly lost world: an escape from crowds, frenetic busyness and high-tech addictions that creep even into presumably placid, reflective sports like fly fishing.

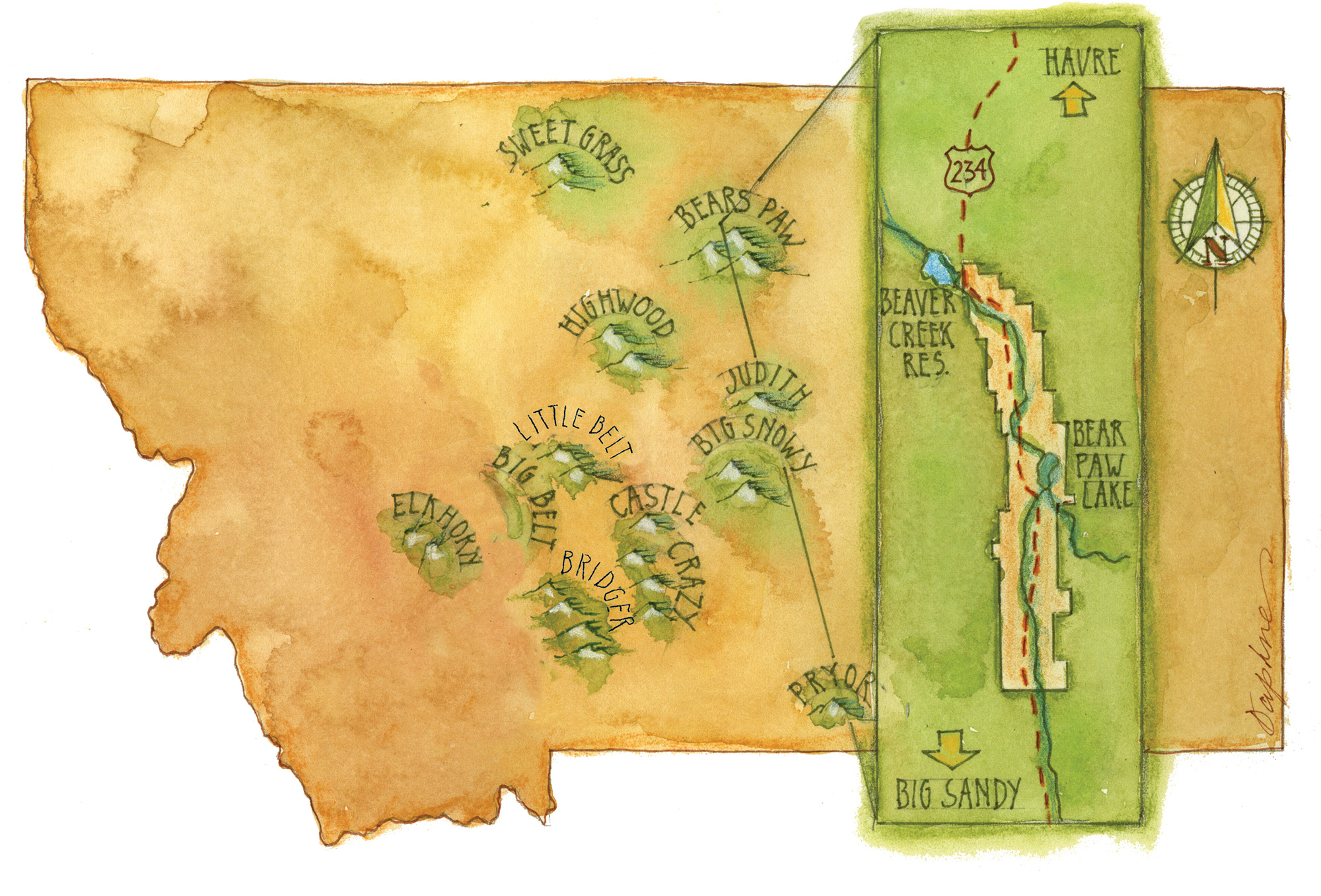

The island ranges in central Montana alone are numerous enough to launch a lifetime of road trips. In addition to the Bears Paws, consider this treasure chest: the Crazies, Snowies, Little Rockies, Highwoods, Pryors, Judiths, Moccasins, Castles and the Sweet Grass Hills. Further west, but still separated from the main spine of the Rockies, lie the Adels, Bridgers, Elkhorns and the Big and Little Belts. There’s more to the south: the Bighorn, Bear Lodge and Laramie mountains, largely or entirely in Wyoming. Since the term is more conceptual than technical, one might even rope in the Black Hills as an island range.

Historically, many island ranges held native cutthroat waters: Yellowstone cutts in streams draining into their namesake river, and westslopes in water feeding the Missouri. Over time, rainbows, browns and brookies were introduced too. In their purest and most isolated form, Montana island ranges are an escape from the drift boat armadas on the best-known rivers like the Yellowstone and Bighorn. Most streams and lakes are small and lightly fished, a retreat for fly anglers who like discovering things for themselves. What you’ll often find is basic fly fishing: wet wading on warm summer days; standard fly patterns, including terrestrials; light rods (perfect for Tenkara rigs); and eager trout with no hint of snootiness.

A Crazy Vision Quest

As I happily sit in the shade along Beaver Creek, my mind flashes back over decades. On my first Montana island range encounter, I was a scruffy teen just before my sophomore year at the University of Minnesota, trying to work out the Rubik’s Cube of my life.

I was limping west along I-90 in an aging, overloaded, underpowered Honda 350 for a couple weeks of adventure before school started again. In addition to fly-fishing and camping gear, the backpack strapped to the bike held existentialist tomes from a humanities class for which I received an “incomplete” during my freshman year — the first of many to follow during a stellar eight-year undergraduate career. Amazingly, as I reflect back, my intent was to compose a brilliant term paper analyzing Camus, Sartre and Nietzsche at campground picnic tables by candlelight. That never happened.

Among the amazing things that did serendipitously occur on my bumbling vision quest was spotting the jagged, igneous, glacier-carved, 11,000-foot high Crazy Mountains looming and shifting phantasmagorically above the rolling prairie northeast of Livingston. I was so mesmerized and drawn to this magnet that I immediately changed my plans to ride directly to the Gallatin. I exited the highway and — in spite of no detailed maps — wound past enormous ranches and along Big Timber Creek to a trailhead, hoisted my pack and hiked way up to Granite Lake, arriving just before dark. I didn’t bother erecting my tent and was punished for that by a rodent who pilfered my socks in the middle of the night. But no matter: It was a blissful sunrise the next morning, rainbows rising on the lake’s placid surface below talus slides and ripsaw peaks. If I had the foresight for a more aggressive hike up to Cave Lake, I could have cast for rare golden trout, the fly angler’s Holy Grail.

According to David Alt and Donald Hyndman’s Roadside Geology of Montana, “The Crazy Mountains are so different and so peculiar that a frustrated geologist might have named them.” That freakishness, combined with their soaring, cathedral-like configuration, helps explain why the Crazies have long attracted seers and seekers. For example, at age 10 in 1857 (according to the Montana Historical Society book, Montana Place Names), “Plenty Coups of the Crow tribe undertook a vision quest atop … the tallest summit in the Crazy Mountains, during which he foresaw the Euro-American invasion and the decline of Native American life.”

Exploring Beaver Creek County Park

The Bears Paw Mountains are sculpted on a more modest, human scale than the lake and cirque-splattered Crazies, topping out at just 6,916 feet on Mount Baldy. But that’s part of their curious charm: The mix of forest and open prairie glades create excellent opportunities for hiking and biking, showcase expansive vistas and boast a rich bio-geographical mix of both Rocky Mountain and Great Plains flora and fauna (even northern boreal species). In The Birder’s Guide to Montana, biologist Terry McEneaney characterizes Beaver Creek County Park as “one of the finest birding areas in northern Montana … truly a birder’s paradise!” Springs, waterfalls and quirky geology add to the enchantment.

Some island ranges — like the Belts and Snowies — include massive amounts of sea-deposited limestone. But the Bears Paws, like other central Montana mountains, are remnants of 50-million-year-old volcanoes that erupted lava, building peaks 160 miles east of the Rockies. Uplift abetted the process, along with subsurface igneous intrusions that seeped through the earth’s crust and crystalized, creating laccoliths — hard, bulging caps resistant to the erosive forces scouring away surrounding sedimentary rock. Geologists Alt and Hyndman further explain: “The Adel, Highwood and Bears Paw Mountains contain great swarms of shonkinite dikes, vertical fractures that filled with magma,” adding that shonkinite “is something of a Montana specialty, even though it does exist in a few other places … around the world.”

Another unusual aspect of Beaver Creek County Park — aside from its sprawling 10,000-acre size — is extreme linearity. At 17 miles long and approximately a mile wide, the stream’s lush riparian zone is well preserved. According to Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, the fisheries are diverse. Brook, brown and rainbow trout thrive in Beaver Creek and associated ponds. Brookies and rainbows, smallmouth bass and walleyes are in Bearpaw Lake, while rainbows, walleye, bass, northern pike and yellow perch thrive in Beaver Creek Reservoir. From top to bottom, there are many alluring campsites on the creeks, ponds and lakes.

With parts of the park’s infrastructure constructed by Civilian Conservation Corps crews during the Great Depression, Beaver Creek County Park has long been the backyard playground for residents of Havre, Chinook, Big Sandy and Fort Benton, as well as people from the nearby Rocky Boy and Fort Belknap reservations. It’s a long double-haul from Montana’s marquee fishing waters, but that’s part of the appeal.

There are intriguing side excursions offering temporary diversion from fishing. Around Havre, Hill County and the Hi-Line, attractions beckon like Fort Assinniboine, dinosaur fossils, wagon trail traces, Great Northern Railroad history, Havre Beneath the Streets (a subterranean urban re-creation, including a bordello and Chinese opium den), and the 2,000-year-old Wahkpa Chu’gn Buffalo Jump. The historic steamboat port of Fort Benton is rich in lore too, including the legendary Grand Union Hotel serving gourmet meals outdoors on the banks of the broad Missouri River.

For Mary and me, the most compelling side trip is the Bear Paw Battlefield, a key unit in the Nez Perce National Historical Park. It was here along Snake Creek, in the bitter cold and snow of October 1877, that Chief Joseph and the tattered remnants of his tribe surrendered; they were just 40 miles from Canada, after eluding the much larger U.S. Army on a daring, circuitous 1,300-mile, summer-long flight. The site of the siege and slaughter is drenched in poignancy; a somber, sacred place immortalized by Chief Joseph’s words: “Hear me my chiefs. I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

The Last Campfire

That night, after wandering the ghostly draws and strategic ridges of the battlefield, we listen to Beaver Creek’s reassuring murmur from our Bears Paw campfire. I reflect on the island ranges I’ve visited over the years: Happiness momentarily alights swallowtail-like with the memories, without need to pursue, define or pin it down.

I think back to the Crazies, 20 years after that first shambolic college trip: Mary and I decide to backpack to the site where I camped at 19, under September’s cerulean skies. But during our second night, the season’s first winter storm unexpectedly strikes, burying our tent in 10 inches of snow. The next morning — while Mary wisely remains deep in her down sleeping bag — I clamber up a narrow canyon in a blizzard to fish an even higher lake. Fifty-mile-an-hour gusts blast the frozen fly line back into my snow-plastered beard; all alone, it’s a dangerous, potentially hypothermic exercise in futility. The trout — smarter than me — are hunkered down like Mary.

I eventually stumble down the precarious, icy path to the tent by dark, nearly frozen but with a wild tale. The next morning presents a stunning new day: The storm has swept east across the plains, a warming sun is up, the snow is rapidly melting. The season’s last butterflies emerge from hiding to hunt fading wildflowers.

As Mary vigorously pokes our fire, my island range thoughts spin skyward with the embers toward a favorite Robert Frost stanza:

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I –

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

What’s in a name?

There are real conundrums when it comes to geographical names in the Northern Rockies, confusing even the most cartographically astute fly anglers. Case in point: Bighorn or Big Horn Mountains? Worse are variants on the Bears Paw Mountains, which many locals refer to as the Bearpaws. For what it’s worth, the Montana State Highway Map uses the former (without an apostrophe), as does the Montana Historical Society’s place name guide. Conversely, the famous nearby Nez Perce historical site is called the Bear Paw Battlefield, while one of the local reservoirs is Bearpaw Lake, at least on some maps.

Here’s the Montana Historical Society’s take on the Bears Paw naming legend, which references a Native American hunter’s encounter with an angry bruin:

“The bear held the hunter to the ground, and the hunter appealed to the Great Spirit to release him. The Great Spirit filled the heavens with lightning and thunder, striking the bear dead and severing its paw to release the hunter. Looking at Box Elder Butte, you can see the paw, and Centennial Mountain to the south resembles a reclining bear.”

The Historical Society also offers suggestions for how the Crazy Mountains took their name: “One story tells of a woman who lost her baby and left the wagon train to wander the mountains, and another invokes an Indian woman who went mad and forever wandered…” •

Fly fishing the sky islands

Here are some beguiling spots to spark your own island range road trip:

Bears Paw Mountains:

Beaver Creek, Bearpaw Lake

and Beaver Creek Reservoir

Crazy Mountains:

Shields River, Big Timber and

Sweet Grass creeks; many alpine lakes

Big Snowy Mountains:

Big Spring Creek and Crystal Lake

Judith and Moccasin Mountains:

Warm Springs Creek

Highwood Mountains:

Highwood and Arrow creeks

Little Rocky Mountains: Beaver Creek

Adel Mountains: Dearborn River

Big Belt Mountains: Trout, Beaver

and Sixteenmile creeks, alpine lakes

Little Belt Mountains:

Smith and Judith rivers, Belt Creek

Pryor Mountains: Sage and Crooked creeks

Bridger Range:

Bridger and Valley spring creeks,

East Fork Gallatin River, Fairy Lake

Castle Mountains:

Musselshell River and its tributaries

Elkhorn Mountains:

Crow Creek, alpine lakes

- Mary Vandenbosch works the riffles on a hot summer day in Beaver Creek County Park, threading through the Bears Paw Mountains.

- Anglers can relax in enticing campsites on Bearpaw Lake, after tangling with resident brook and rainbow trout, along with smallmouth bass and walleye.

- Map by Daphne Gillam (Detail)

- Interesting side trips near the Bears Paw Mountains include historic Fort Benton, the head of 19th century navigation on the Missouri River.

- The road less traveled: A peaceful evening in the Bears Paw Mountains, far from the drift boat parades.

- While cutthroats are native to many island ranges, brook (pictured), brown, and rainbow trout are common today.

- The Crazy Mountains and its trout-filled tarns are both forbidding and beautiful after an early fall snowstorm.

- Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains are one of the largest, highest, and most spectacular island ranges in the Northern Rockies, with streams like the Powder (pictured), Paintrock and Tongue, along with dozens of alpine lakes.

No Comments