01 Feb Montana Mayflies

All mayflies are beautiful, but especially so to the fly angler’s eye. That all mayflies feed and fatten trout makes them, to that eye, more beautiful yet. I may have a favorite, and that favorite could change, but each Montana mayfly is surely the favorite of many and, I’ve not the least doubt, fully deserves to be.

The extraction of its entire self from its underwater skin, its shuck, at the surface of a river, though nirvana to fly anglers, is only the thinnest slice of a mayfly’s life and is called “hatching” by anglers. (It is a fact, though, that not all mayflies follow the standard model of hatching in open water: Some emerge from their shucks under the water, and a very few crawl up from the water to hatch.)

When scatterings to mobs of some mayfly or another are on a river, it’s an almost covert but magnificent show. To the passing hiker or meadowed-bank picnicker, a mayfly hatch, if they even notice, is a curious stippling of bugs on and flitting up off the water. Enraptured, the fly angler looks much closer, and sees much more: bent stem-legs radiating from thoraxes depress the supple surface of water; slender abdomens arch; needle-thin tails raise; long-triangle wings part; the insects perch on quick or quiet, smooth or ruffled currents; and perhaps wave still-moist wings in the dry air. This venerable stage on which so many dry flies have been designed — about which so many reverent words have been written by fly-fishing authors — is the dun stage.

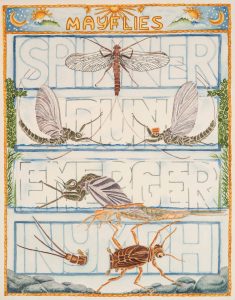

The preponderance of a mayfly’s life is spent as a crawly wingless nymph down among rocks or weeds. The nymph swims up through the river to hatch into a dun. During its troubled escape from its shuck, a mayfly becomes what anglers call an emerger. The dun flies off to fully mature over as little as a half hour, but usually over days, becoming a spinner. Once her eggs are fertilized, the female spinner returns to the water to release the eggs as her final act, dying there on the surface.

All these stages of a mayfly’s life feed trout, thus all are imitated by artificial flies.

But the hatch, to many anglers, is the greatest of mayfly blessings. Mayflies, all of a type (let’s say, pale morning duns), identical in color and size, hatching together. Over minutes to hours, they keep coming, keep popping out, dotting the face of the water. A real bonanza for trout — focused, gathered, feeding in earnest. What more could a fly angler want?

And so, to capitalize on this display, fly tiers have developed their own versions of the bug. A bug of various habits and habitats, of various colors, sizes, and personalities. Here are my ruminations on a few.

The Logical Champ

I suppose my favorite mayfly of Montana trout streams really should be the pale morning dun (PMD). It is, after all, a cheery yellow all over (though the color does vary), and the real clincher: It is the most reliable and long-winded mayfly hatch throughout the state. In fact, throughout the West. I’ve seen ample hatches on Oregon’s Metolius River in May, and a strong hatch on Colorado’s South Platte as late as October.

Poly-Wing Spinner Trico

But, despite the long season of its hatching, the PMD has a problem: Though I’ve fished Big Sky Country creeks and rivers every month from April into October, I fish them most often in September, and I’ve yet to find PMDs hatching well during this, my favorite, month. Consequently, this one can’t be my top Montana mayfly.

But I can love it, regardless. Love it for all the wonderful fishing it’s given me on the Bitterroot, Big Hole, and Poindexter Slough. I love the sight of PMDs atop currents, drying new wings amid trout, noses up, busily picking off the intricate beauties.

Whether or not the PMD deserves my top billing among its Montana fellows, it certainly deserves a romantic scene or two. Indeed, I’ve had some grand moments with this accommodating, sunny little chap.

When I found PMDs hatching on the Big Hole River, it was during an uber-wet year. The snowpack was insane and, through its sheer volume and persistent cool weather, kept pouring itself into the river even when I was there — in August. Frequent spring and then unseasonably frequent summer rains contributed heavily. Water too low and too warm for the good of the fish — certainly not water too high — should, in that month, have been our concern. A truly anomalous year. But the duns and the trout both obliged us, regardless.

Working not from summer-baked bars of dry gravel and rock but from grassy, treed banks along the swollen flow, I had to watch where I aimed my back casts. But no casts were long: The trout had been driven to the boulder-baffled flows along those banks to escape all that angry current. I worked upstream, dropping a floating emerger fly (an imitation of a shuck-emerging insect) ahead of repeating rises, and the action was steady and good. A 17-inch brown was my best fish of that day, an especially fine trout for being caught on the rise and on a dry fly of just size 18.

I’ve had other bright meetings with the Montana PMD, but other intriguing mayflies remain for us to explore.

The Runt

Various types of mayflies divide up a river. Some can’t even find their niche. Tricorythodes, or the trico, requires silt, and silt forms only where waters move slowly — steep quick mountain streams hold few tricos or, more likely, none. But tricos, by way of being such odd mayflies, really are intriguing. They’re almost alarmingly quick to mate after hatching, are very tiny, often abundant, and can draw up surprisingly large trout to take them in soft rises. Mostly, we fly anglers concentrate, as do the trout, on the helpless spinner stage and show the trout diminutive size 22 and 24 flies, like the Trico Poly-Wing Spinner.

Most mayflies aren’t as picky as the trico. For example, I’ve found hatches of PMDs in big Montana rivers and in small ones, too. In unhurried weedy flows and in rocky racing ones. Same goes for the dinky blue-winged olive — I’ve found it in all kinds of moving water. But now is too soon to address that one.

Second Place, for Now

Mahogany Dun Comparadun

The likeliest current contender for becoming my favorite Montana mayfly is the mahogany dun. In general, though, it’s no headliner: Medium-sized to quite small, it’s plain, for a mayfly, and normally hatches in only modest numbers (based on my experience). Yet, it has crept way up in my personal poll. Its underside really is, when not tan or gray, a reddish-brown mahogany. Most of the ones I find are of fair size, and my fascination with fishing tiny flies among the tiny mayflies of late season can suffer when bigger and easier mahoganies are around. I can actually see, without strain, a size 14 Mahogany Dun Comparadun 40 feet out on a jigsaw puzzle of dark current lines. See it, that is, till a westslope cutthroat takes it down.

The Dazzler

The Western green drake will likely never beat out Baetis (which I really will address) or the mahogany dun in my playful, trivial contest — I simply do not encounter it often enough for that. But this big mayfly is striking: nearly black of wing, a stouter-than-most body of forest green splashed and ringed with strong yellow. Such a beauty and bold on the water.

When I think of the Montana green drake, I remember a day on the Bitterroot. During a steady hatch of PMDs and a good rise of trout in response, the drakes began showing. Rainbow and cutthroat trout stayed on the smaller mayflies at first. Then, as the afternoon wore on and tree shadow covered ever more of the water, the drakes took over and the trout turned to them. I changed flies — from a Morris Emerger matching the PMD to the green drake version of that same half-floating fly. Fishing remained steady and good, but took on a new flavor that was by no means inferior.

Certainly, if I ever really take up chasing down Montana green drake hatches, that big, sturdy, showy eyeful could, indeed, become my favorite state mayfly.

Highly Unlikely, but Deserving of Respect

Morris Emerger Green Drake

The black drake — which fly fishers sometimes refer to by its scientific name, Siphlonurus — is a mayfly anomaly. It’s among those few that swim not up in open water to hatch, like most mayfly nymphs, but ashore instead. Siphlonurus then crawls from the water, still a nymph, to slip from its shuck up in the air on grass, reed, or rock. The nymphs and spinners, not the duns and emergers, feed the fish. I haven’t seen many black drakes in Montana — though certain streams must hold many — and, in fact, have encountered strong hatches only a very few times in all my decades of fishing mayfly hatches. So, despite my fascination and respect for Siphlonurus, no way can it be my Montana favorite; infinitesimal chance it ever will.

The Winner

Despite strong arguments for the PMD, my favorite Montana trout-stream mayfly is, unquestionably, the blue-winged olive. (Mayfly nicknames — such charm! Yet, I often use the scientific Latin name for this one — Baetis, pronounced “beetus” — because it’s more economical than “blue-winged olive” or even the acronym “BWO.”)

Though Baetis can hatch any time of year, I don’t consider it a year-round mayfly. September through October (when I fish it most) and April and May are when it shines; it hatches heaviest during these months — when few other hatching insects are out to compete with it. The blue-winged olive really is blueish of wing (though, arguably, just gray, if your eyesight lacks imagination), and its abdomen and thorax commonly are a true olive.

Anatomical BWO

A good Baetis hatch puts a diminutive carnival of gentle gray motion on a stream. Some of the insects turn quiescently on swirls of current, others work wings, even bounce on the water as they experiment with first flight. The trout come up to add their counterpoint. I think of a creek not so far from Missoula where, one cool day in late September, 10- and 12-inch cutthroat trout like lazy porpoises lifted and veered, putting noses over duns in the water, passing alongside their hollowed shelters behind boulders.

Another fall and a hundred miles east of Missoula, I crouched where a great boulder pressed some glassy flow from a deep pool on the broad Missouri River into a quickened light chop along the shoreline. The river’s especially tiny strain of blue-wings (my entomologist friend Rick Hafele later determined they were, in fact, blue-wings) were pushed together on the funneled water. The trout were most interested in them, though at first, it seemed they weren’t: few showed in rises. But, just below the chop pouring in at the head of the small channel, where the current eased, an ample number of them were taking the up-swimming nymphs just short of the surface. I figured that out by trying a size 20 nymph, an Anatomical BWO, suspended below the white ball of a pea-sized strike indicator.

I’ve fished Baetis in lots of Montana rivers and creeks: in the Bitterroot and its forks, in the Gallatin, in misnamed Rock Creek (that’s no creek), and others. After so many splendid hours spent with this somber, small, elegant insect, it’s no wonder it tops my list.

All mayflies really are beautiful. Beautiful in form, and beautiful in the intricacy of their brief, extraordinary lives.

Over the past 30 years, Skip Morris has written 23 books on fly fishing and tying flies and over 300 magazine articles and essays. He lives with his wife, Carol, and their willful cat, Olive Penderghast, on Washington’s lush Olympic Peninsula amid all its varied opportunities for both fresh and saltwater fly fishing; skip-morris-fly-tying.com.

Carol Ann Morris is a fly-fishing photographer, speaker, videographer, and artist/illustrator. She partners with her husband, fly designer and author Skip Morris, on his fly-fishing books, articles, and instructional videos. Over the past three decades, Morris’ photographs and paintings have appeared not only in most of her husband’s 23 fly-fishing and -tying books, but also on the covers and interior pages of such magazines and books as Gray’s Sporting Journal, Fly Fisherman, Yale Angler’s Journal, American Angler, Fly Fishing & Tying Journal, and America’s Favorite Flies.

Sherry Poole Todd

Posted at 15:07h, 28 FebruarySheer poetry, Skip! Even if you’re a novice, once in awhile fisher, it’s lovely to read your vivid imagery along with CA’s fabulous drawings!!

ken mitchell

Posted at 23:00h, 01 MarchAnother fine essay Skip Morris informative and fun read with depth to make you think , well accessorized with Carol Morris artwork, like putting a bow on a well-wrapped package. Yet both writing and art are strong enough to stand alone and take the test of time