02 Feb Montana Hoppers

The chief problem for the grasshopper, in terms of its status among fly fishers, is the mayfly. The mayfly — delicate, slender, standing quietly on a river, the soft peaks of its full wings angling high — is the insect that, to trout-stream fly fishers, embodies all that is refined and poetical about their grand sport. The grasshopper, contrarily, is a chunky, jittery, clumsy brute, violent both in its leaps and its landings.

To fish a hatch of mayflies is to lightly and precisely cast a wispy fly to feeding trout whose noses rise softly just above water and disappear, over and over, subtracting from the flotilla of drifting beauties. (A hatch, in fly-fishing lingo, is a migration of identical insects, of any sort, from their long lives underwater up and out to free their new wings and rise into the air.) Grasshoppers don’t hatch, and grasshopper fishing lacks all the grace and buoyancy of a mayfly hatch. Grasshopper fishing is slamming a beefy fly onto water with the hope that a trout will savagely rush it. A drunken brawl. But whatever it lacks in grace and refinement, grasshopper fishing does not lack in excitement.

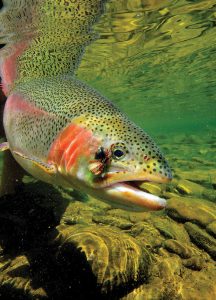

A hopper rides a Montana river: If a trout spots the bug coming in, the ride will probably end violently. Photographed by Barry And Cathy Beck

All due deference to the mayfly and the fascinations of its fishing, its fishing is rarely as wild-eyed exciting as the vicious right cross a trout often gives a grasshopper fly. I’ve watched trout execute this pugilistic move on both grasshoppers and the flies they inspire many times through my long career as an angler, and most of my hopper fishing — though I’ve practiced it in Oregon, Idaho, Colorado, California, and Canada — has been in Montana.

A Montana trout stream in July, August, or September can be a wonderful place to be an angler when hoppers are around. Some Montana years are big hopper years; you know you’ve come during a big year when grasshoppers fidget before you on small town sidewalks and fishing trails cut through tall grasses. A hopper turns in jerky movements of its little forelegs and deer-thighed hopping legs as you come near. Then, it stops, tensing, and, just when you’re close enough to grab for it, springs high and away. Maybe its wings open out dark against the tan grass. The hopper doesn’t know you, doesn’t want to know you, and certainly doesn’t want to be caught by you.

But you do want to catch it.

When grasshoppers must compete for turf alongside a stream, a grasshopper-imitating fly is almost surely right. Photographed by Jeremie Hollman

You want to catch it to check its size and the color of its stumpy body, so you can match that color and size in your fly. If you do catch the grasshopper, it struggles and surprises you with its powerful kicking. It doesn’t like you. It spits sour tobacco juice on your skin.

Yet, it has its appeal. Generally, as insects go, most grasshoppers are sort of handsome — albeit in a bullish way — in their complexity of colors, markings, and symmetry. But there are many kinds of grasshopper. According to the National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Insects & Spiders, there are some 1,000 species of grasshopper and cricket (both insects belong to the order Orthoptera) in North America alone. Some hoppers, to my eye, really are plain ugly. There’s a great dusty looking and blobby one that offends me in particular. It looks as though carved from a bar of creamy gray soap.

“Pardon me, but might a little social distancing be in order?” Photographed by Barry And Cathy Beck

Flies that imitate grasshoppers are another matter: They’re never annoying, and nearly always impressive and intriguing. It takes a lot of the fly tyer’s fluff and hair and fur (and whatever else) to make a trout fly as big and beefy as a grasshopper, particularly one that carries its shape and key features.

Size is the grasshopper’s finest quality from the fly fisher’s perspective. And from the trout’s. (Though I suppose it’s possible trout would rank grasshopper flavor over size. I’ll never know, because — I swear it to God — I will never taste one.) That graceful mayfly we saw earlier is but a nibble compared with the feast that is a grown hopper. Of the stream-born insects trout eat and fly fishers commonly imitate with their flies — the mayfly, of course, and the caddisfly, the stonefly, the midge — only a very few of the stones and one caddis can match the meat-serving of an average-size grasshopper. A floating hopper can inspire a big trout that has nearly given up the practice of feeding at the predator-risky top of the water to charge up with murderous intent. Fly fishers know this and, thus, the grasshopper earns from them its clunky respect.

Could this slim, stately mayfly have less in common with a bull-like grasshopper? Photographed by Nick Price

Grasshopper fishing usually goes something like this: It’s midsummer, and you’re looking up a Montana trout stream that winds down to you through banks of tall grass. The chill of the high-altitude night is about gone and now hoppers that were quiet an hour ago leap and soar in their limited flight — one springs up near, then one farther away, sporadic action heightened whenever a breeze stirs the insects up.

A colossal oops from a trout’s perspective: mistaking a grasshopper fly for a grasshopper. Photographed by Barry And Cathy Beck

Soon, you’re kneeling in shallows just down- and across-stream from a corner where water dark with depth slows against a grass-furred bank, a bank sculpted by high-water times to a steep drop of about 3 feet. You swing the line up and back, pause, and punch it forward to snap the big fly out. It drops above the dark water, where you want it. You can see the fly 30 feet upstream. It bounces down on light ripples of current, but only by memory and imagination can you see its head of deer hair, packed and razor-sculpted to the clean shape of carved wood, its great legs of dark pheasant-tail fibers knotted to angle, as though jointed.

In most streams, very little will bring a hefty brown trout like this one up to feed at the surface of the water. But a full-grown grasshopper? That’ll do it. Photographed by Fish Eye Guy Photography

Your eyes, in actuality, do see the head of a 3-pound brown trout burst from the water at the bobbing fly. You pause, to let the trout close its jaws on the thing, and then you give the line a sharp tug to sink in the hook.

The battle is on!

No Comments