22 Nov MASTERPIECES OF 19TH CENTURY PLAINS AND PLATEAU INDIAN ART

Since its original facility opened in 1927, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming has become a 300,000-square-foot historical center consisting of five separate museums. Its flagship, the Buffalo Bill Museum, chronicles the life of William F. Cody [1846–1917], a Western icon and arguably the first truly international celebrity. Institutional growth occurred incrementally. The Whitney Western Art Museum was established in 1958, followed by the Plains Indian Museum in 1979, the Cody Firearms Museum in 1991, and the Draper Museum of Natural History in 2002.

Upon close examination, decorative strips embroidered with the rare quill wrapped horsehair technique exhibit a distinctive, filament-like structure. The quill-wrapped horsehair ends are usually wrapped together as single units for a short distance (1–2 cm) before dividing into parallel lanes. | QUILL-WRAPPED HORSE HAIR SHIRT, ATTRIBUTED AS “NORTHERN PLAINS,” CA. 1850. PAUL DYCK PLAINS INDIAN BUFFALO CULTURE COLLECTION. COURTESY OF THE BUFFALO BILL CENTER OF THE WEST, ACCESSION NO. 202.1184

Currently one of the foremost repositories of Plains Indian art in America, the Plains Indian Museum’s collections originated with regalia and accouterments utilized by tribal participants in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows held between 1883 and 1913. Targeted acquisitions — most notably the Spohr, Chandler-Pohrt, and Dyck collections — enhanced the quality and historical depth of the museum’s holdings, and today, the assemblage of material that predates 1850 is exceptional. In the richly illustrated book Plains Indian Buffalo Cultures: Art from the Paul Dyck Collection, Arthur Amiotte, a renowned Lakota artist, describes some collection pieces as “examples of artistic achievement equal to historical masterpieces from ancient cultures of the Western Hemisphere and the world.”

Viewed through the prism of history and interethnic relations, the masterworks in the collections of the Plains Indian Museum were crafted during a period of extraordinary cultural change and upheaval. Despite the end of bison-based nomadism and the loss of tribal autonomy, the traditional arts remained a protected bastion against forced assimilationist policies imposed by the federal government. When asked why her Apsáalooke ancestors continued to bead throughout the dark, early years of the reservation period, Lorena May Walks Over Ice informed Barbara Loeb in a 1990 article published by Montana: The Magazine of Western History, “because they liked to, and because [the Courts of Indian Offenses] let them.”

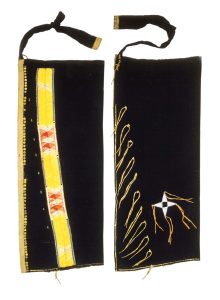

Embroidered with the multi-quill plaiting technique, quillwork on this piece exhibits the yellowish-orange background that typifies reservation-period Fort Berthold-style quillwork. Its composition, however, dates back to at least 1834, as evidenced by its presence in Karl Bodmer’s magnificent portrait of Pehrishka-Ruhpa (Two Ravens), a distinguished Hidatsa leader. | MAN’S QUILLED LEGGINGS, HIDATSA, CA. 1885. COURTESY OF THE BUFFALO BILL CENTER OF THE WEST, ACCESSION NO. 202.47

Ceremonial shirts rank among the most visually impressive objects produced by Plains Indian women. George Horse Capture, a Gros Ventre (A’aninin) scholar and curator of the Plains Indian Museum from 1979 to 1991, offered the following tribute to these magnificent garments in a 2001 exhibition catalog: “Earned through acts of bravery, decorated in honor of great deeds, reflecting the deepest spiritual beliefs of the people who made and wore them, they are the closest we are ever going to get to our forefathers.”

The “Red Cloud” shirt is the best known shirt housed in the Plains Indian Museum. The technical precision with which it was crafted and embroidered, as well as the complexity and brilliant compositional contrasts that characterize its ornamentation, imbue this garment with extraordinary beauty. Hair-fringed shirts, particularly those produced by the Lakota and Cheyenne, have been described as “scalp shirts” because locks of hair from enemies slain in battle were used to decorate them. Art historian Colin Taylor offers an alternative perspective in his analysis of the Red Cloud masterpiece, which was published in his 1990 doctoral dissertation. He contends that its 238 human hair and 68 horsehair locks are most accurately interpreted as expressions of allegiance or support by the people this shirt-wearer represented. Taylor also makes a compelling argument that compositional elements in its beadwork symbolically invoke the 16 manifestations of sacred power subsumed in Lakota as Wakan Tanka, a term of address commonly, but imperfectly, translated as “Great Spirit” or “Great Mystery.”

Another hair-fringed shirt, attributed as “Northern Plains, ca. 1850,” is decorated with quill-wrapped horsehair. Typically associated with the Mountain Crow (Apsáalooke) and eastern Plateau peoples, notably the Nez Perce (Nimi´ipuu), shirts embroidered with this technique were most fashionable before 1870. Surviving examples are rare, but they are “uniform in structure and detail,” according to art historian Bill Holm in an article published in Studies in American Indian Art: A Memorial Tribute to Norman Feder.

From their earliest availability, the Upper Missouri tribes prized blue beads above all others. Unfortunately, Meriwether Lewis severely underestimated the magnitude of that preference. He later informed Thomas Jefferson that, “were his journey to be performed again, one half or 2/3 of his stores in value, should [consist of blue beads].” | SADDLE BLANKET AND MAN’S LEGGINGS, ATTRIBUTED AS “UPPER MISSOURI REGION, MONTANA OR NORTH DAKOTA,” CA. 1830-50. | CHANDLER – POHRT COLLECTION. COURTESY OF THE BUFFALO BILL CENTER OF THE WEST, ACCESSION NOS. 403.164 AND 202.440

Collection histories, archival photographs, and oral traditions suggest that ownership of these garments was relatively widespread. Artists who crafted them, however, adhered to a complex and highly integrated set of stylistic conventions that are almost formulaic in their consistency. If quill-wrapped horsehair shirts were not produced exclusively by the Crow, the Apsáalooke-Nimi´ipuu alliance served as the primary conduit for their dissemination to other Plateau tribes.

Quill embroidery has been a sacred practice among the Arapaho, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, and Gros Ventre. According to Jeffrey Anderson, an anthropologist and the author of Arapaho Women’s Quillwork: Motion, Life, and Creativity, “meticulous and concerted replication of form, color, proportion, and pattern under the instructive authority of elders” were hallmarks of Arapaho [and Cheyenne] quillwork during the 19th century. This ritualistic approach contributed to the establishment of iconographic forms.

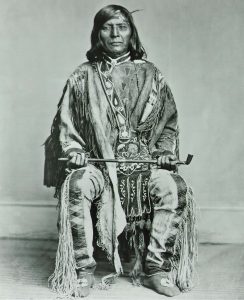

This photograph of Timothy, a Christianized Nez Perce leader, illustrates the persistence of earlier quill working traditions and, almost certainly, the impact of intertribal trade. Most notably, the decorative strips on his leggings exhibit the intricate pattern of diamonds and hourglasses, as well as seams down the longitudinal axes of strips, which so typified River Crow-Hidatsa multi-quill plaited quillwork. | TA-MA-SON; TIMOTHY, NEZ PERCE. PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN BY A. ZENOS HINDLER ON JUNE 3, 1868. NATIONAL | ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHIVES, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, NEGATIVE NO. 2923-A

This process is exemplified by the longevity of design compositions on a pair of leggings that the museum credits as “Hidatsa, ca. 1885.” Interlocking diamond and hourglass motifs, divided internally into a matrix of tiny diamonds that alternate in color, typify plaited quillwork. This embroidery technique was utilized most extensively by the River Crow and Hidatsa. Use of this pattern persisted for more than 50 years, as evidenced by its depiction on regalia in portraits by Karl Bodmer (1834) and Rudolph Friederich Kurz (1851). Virtually identical design elements appear on ceremonial shirts attributed to the period from 1830 to 1860 and blanket strips that adorn Crow war-exploit robes collected in 1837 and 1861.

Glass beads, destined for the Northern Plains, entered fur-trade inventories during the early 19th century. This novel medium provided a culturally blank slate upon which artists could experiment. Its status as a secular art form, however, did not fundamentally undermine the spirituality with which Plains Indian women approached their work. The renowned Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday eloquently proves this point in a Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology exhibition catalog where he recounts childhood memories of Aho, his grandmother. She was “a beadworker of extraordinary skill” whom Momaday observed with rapt attention. Even then, he realized that Aho’s artistry was “the creative expression of her spirit, like prayer, an expression that came from the center of her being.”

This bow-case quiver illustrates the challenges associated with making a definitive tribal attribution for objects embellished with Transmontane-style beaded art. Nearly a dozen Plains, Plateau, and Great Basin tribes employed facets of this regional style to varying degrees and different object types. Given the discrepant evidence provided by the photographic and ethnographic records, one can conclude only that this masterpiece was most probably of Crow or Nez Perce origin. | OTTER SKIN BOWCASE-QUIVER, CROW, CA. 1875. ADOLF SPOHR COLLECTION. COURTESY OF THE BUFFALO BILL CENTER OF THE WEST, ACCESSION NO. 102.20

The earliest collections of Northern Plains material culture were embellished with beads 3 to 5 millimeters in diameter that are commonly but erroneously described as “pony” beads. Journal entries by Lewis and Clark, as well as François-Antoine Larocque, a French-Canadian fur trader, indicate that, in 1805, a pronounced preference for these blue and white beads already existed among the tribes that they encountered, including the Apsáalooke.

A composite image of an elaborately decorated saddle blanket and pony-beaded leggings illustrate this color preference and several other characteristics of the Upper Missouri style extant prior to 1850. These attributes notably include block-style design elements of alternating color, insertion of red cloth panels as contrasting accents, and the predominant use of Crow-stitch embroidery, which is visibly recognizable by the wavy appearance of beaded rows.

The introduction of smaller “seed” beads, available in many colors, facilitated stylistic diversification during the second half of the 19th century. Among the various artistic traditions that coalesced into distinct tribal styles is Transmontane beaded art, particularly the work of its foremost practitioners: the Apsáalooke. Crow-Nez Perce otterskin bow-case quivers are an object type embroidered in this style. Only six completely intact examples are known to exist in museums and private collections, according to Holm.

One of these pieces, acquired by Adolf Spohr and attributed by the Plains Indian Museum as “Crow, ca. 1875,” was crafted from three pelts, which were used for the bow case, quiver, and bandolier, or carrying strap. The bow cases are remarkably short. In Holm’s opinion, this may reflect the use of compact, but extremely powerful, sheep-horn bows, which were favored by tribes most closely associated with otterskin bow-case quivers. Three pairs of beaded ornaments, with different color schemes and design compositions, adorn primary decorative fields.

Artistic treatment of compositional elements on this piece closely adheres to reservation-period Cheyenne aesthetic tradition. However, the deeply stepped borders of triangular motifs and use of metallic beads, most notably in hexagons, strongly suggest a more recent date of manufacture. Gilt faceted beads are a particularly sensitive chronological marker, since they commonly appear in Plains Indian beadwork crafted between 1885 and 1895. | CRADLE, CHEYENNE, CA. 1870 (?). COURTESY OF THE BUFFALO BILL CENTER OF THE WEST, ACCESSION NO. 111.18

Historic photographs place this object type in the hands of Plateau peoples, especially the Nez Perce. However, Captain W.P. Clark observed in his 1885 monograph, The Indian Sign Language, that the Apsáalooke made extremely handsome otterskin bow-case quivers as well. According to his description, their bandoliers were “heavily beaded and fringed with ermine.” Clark further emphasized that “[t]his particular style of quiver is as much a specialty of the Crows as the blanket is of the Navajos.”

Emma Hansen (Pawnee), curator for the Plains Indian Museum from 1991 to 2014, characterized cradles as “[t]he highest form of artistry of Plains Native women.” The Cheyenne cradle pictured on page 139 also demonstrates that no 19th-century Plains Indian object type communicated tribal affiliation more precisely than these “house[s] for the beginning of life,” as Linda Poolaw (Kiowa-Delaware) describes them in a Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology exhibition catalog. Northern Arapaho women, for example, produced a unique type of quilled cradle. Similarly, the closure system of Apsáalooke cradles — which employed three pairs of beaded tabs — and the bilateral asymmetry of their Kiowa counterparts — a hallmark expressed through the selection of different background colors and design compositions — are also discernible marker traits.

Momaday contextualizes the origin of the Kiowa cradle style in terms equally applicable to the Upper Missouri tribes. Reservation-period cradles welcomed new life to the tribal circle when many populations were approaching their nadir. Consequently, as Momaday observes, Kiowa cradle-makers were driven primarily by the desire to express thanks and hope that their newborn children would live “full lives and carry the blood of their ancestry beyond the moment in which extinction seemed most imminent.”

The spiritual motives underlying this principle were, perhaps, most perfectly exemplified by Arapaho belief systems. According to art historian Marsha Bol, in an article published in Painters, Patrons, and Identity: Essays in Native American Art to Honor J.J. Brody, “Arapaho women, when supervised by the old ones who had access to the extra-human, were temporarily endowed with the capability to perfectly construct a cradle, thus showering supernatural blessings upon the child.”

Readers who have not previously visited the Plains Indian Museum will discover that these masterworks and others in the collections of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West comprise a comprehensive assemblage of material from the classic period of Plains Indian art, ca. 1870–1910.

Douglas A. Schmittou is a freelance writer in Billings, Montana. His research focuses on travel in the Northern Rockies; evidence-based wellness protocols; and 19th century Plains Indian art, material culture, and ethnohistory. His work has appeared in Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Plains Anthropologist, and American Indian Quarterly.

No Comments