15 Jul Marks of Strength

ONE OF DWAYNE WILCOX’S LEDGER DRAWINGS shows a Native man and woman riding a charging white horse. Its tail flies behind it and its neck strains to surge forward. The man in front holds onto his companion by the hip while she throws her head back in an expression of freedom. Given their body language, you’d expect them to be galloping their white steed across the open plains. But instead, they sit astride a mechanical horse, something children ride at the mall outside of a department store. The days of charging across an open field are few for many Plains people today.

“We’re still here and vibrant, but our images are kind of caught in a time warp. We need to upgrade them from the warrior-and-pony type of art,” Wilcox said. “I’m satisfied that those images were covered by the people that lived at that time.”

Wilcox, a self-taught Oglala Lakota artist, creates images of contemporary Native life using pictographs and paper from the 1800s. As a ledger artist, he describes his work as a visual language, using humor and social commentary to document Native life today.

Ledger art originated during the 19th century. Plains nations had a longstanding tradition of preserving oral histories pictorially by drawing on rock walls and buffalo hides. As Europeans arrived during the first decades of the 1800s, they brought with them new economies, worldviews and religions. They also brought ledger books — ordinary items used for keeping records. Native Americans acquired ledger books through trade or plunder and the books became the next medium for documenting biographies in the absence of written language.

“The original people that found these books with words written on the paper couldn’t read, so they looked at them as decorative marks,” said Wilcox. “They were drawing their warriors over those marks to show their strength. In a way, it was an act of rebelling.”

The earliest surviving ledger art of the Northern Plains is dated 1834 and was created by Mandan warriors Four Bears and Yellow Feather. Despite this early beginning, drawings were produced in their greatest numbers from 1870 to 1890, writes James D. Keyser in his book The Five Crows Ledger. Examples of early drawings from the last quarter of the 19th century are known from nearly every tribe on the Northern and Central Plains, he writes. Earlier works often depicted battle scenes, but as the style evolved, subject matter such as courtship and ceremonies appear.

Early ledger books were prized for their portability and were often passed between friends and passed down to relatives or carried into battle. Researchers estimate that around 200 completed ledger books exist today in institutional and private collections. Most ledger books have been disassembled because individual pages fetched higher prices at auction, according to the Plains Indian Ledger Art Digital Publishing Project.

Nearly 200 years later, ledger art has moved from serving a functional purpose of bibliographic expression to a modern purpose of artistic expression, and today’s ledger artists mold the historic art form to fit contemporary needs. Wilcox, who’s researched ledger art at the Smithsonian, described ledger art as a “pop movement” within the Native American art scene for its growing popularity.

The genre saw a major resurgence around five years ago, said John Torres-Nez, deputy director for the Santa Fe Indian Market, a 91-year-old Native art market known for its size and prestige. The market had a category for ledger art for quite some time, he said, but it received few entries until recently. Ledger art was reinstated as a competitive category in 2009 and many entries depict traditional subject matter, which also sells better, he said.

Blackfeet artist John Isaiah Pepion, from Kalispell, said he hopes to address more contemporary issues — including water rights, drilling for oil and alcoholism — as he develops as an artist. But today he’s comfortable drawing a traditional style influenced by his cultural background, dreams and history.

“To me, [ledger art] is like a form of resistance, because I can take this paper and put my cultural history, that was forbidden at one point, on there,” Pepion said. “It’s a way of resistance, and I feel like a warrior through my art. I can’t go out and count coup on other tribes; the only way I can count coup is through my art, and it makes me feel like I am a warrior today.”

Traditional ledger drawings were drawn on a flat plain without foreshortening and using mostly primary colors. Some contemporary artists retain this style, avoiding shading and shadows and using a limited color palette. Early and contemporary ledger drawings tend to be highly symbolic. Some early drawings were annotated with descriptions that explained the work’s symbolism or identified subjects. These annotations have helped researchers understand the symbolism in even earlier pictographic drawings, writes Keyser. Stuart Brings Plenty, an Oglala ledger artist, annotates some of his work in a similar manner, including descriptions in both Lakota and English.

Terrance Guardipee, from the Blackfeet nation, said he seeks to recreate historic stories in a contemporary manner in his ledger drawings as a way of preserving his tribal history. He stylizes some aspects of his work, for example using collage and bright colors, while keeping traditional Blackfeet themes and symbols. His work is also closely tied to his homeland — Montana.

“I want to represent my people, Blackfeet country and incorporate as many Montana materials as I can find, mostly from the 1800s,” he said. “When people purchase a piece, they are not only purchasing Blackfeet history, but also Montana history.”

Wilcox and Pepion have ledger drawings on display at Indian Uprising Gallery on Main Street in Bozeman. The gallery will host exhibits for Pepion this summer, along with other notable artists. Specializing in contemporary art from the Northern Plains, specifically pictographic and ledger drawings, gallery owner, Iris Model, said she felt a commitment to provide a showcase of contemporary Native work because it wasn’t very visible or accessible unless you wanted to travel to Santa Fe.

“It became very apparent that it was a very lively, vigorous contemporary art scene,” Model said.

Just as natural pigment paints and bone and stick brushes gave way to colored pencils and crayons in the early 1800s, ledger artists will continue to define the genre according to their own worldview and influences. And art will continue to express and preserve cultural ideas throughout time.

Contemporary Ledger Exhibitions, Summer 2012

Indian Uprising Gallery, in Bozeman, will celebrate the work of artist Monte Yellow Bird with an opening reception at 6 p.m. on June 13. Yellow Bird, a member of the Arikara and Hidastsa Nation and a ledger artist, is interested in the harmonic balance between humanity and nature. His work seeks to honor his heritage and spiritual roots using both a Modern and contemporary art tradition. Indian Uprising will also host Blackfoot artist John Isaiah Pepion with an opening reception at 6 p.m. on Aug. 10. The up-and-coming ledger artist has drawn professionally for two years. He often attends cultural activities to observe and listen, asking questions of elders and applying that knowledge to his work. Both shows will hang for one month and the artists will be on hand to discuss their work during the openings. For more information, call the gallery at 406.586.5831.

The Missoula Museum of Art will host Oglala Lakota artist Dwayne Wilcox for his one-man-show titled Above the Fruited Plain, at the Missoula Art Museum June 1 through Oct. 21. Wilcox’s ledger drawings have intrigued collectors and scholars over the last decade for their updated themes. His work is represented in prestigious institutions including the Peabody Museum and the Hood Museum of Art. His work is also part of the permanent collection at the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls. Contact the Missoula Museum of Art, 406.728.0447, for more information.

The First People’s Market a free outdoor event from July 13 to 15 in Uptown Butte, will offer a variety of work by Native artists and craftspeople, including ledger drawings. View the work of Spokane artist George Flett, who sometimes incorporates mixed media like embossed paper in his work. In addition, you can also find work by Blackfeet artist Terrance Guardipee, known for his use of collage, and work by Northern Cheyenne artist Alaina Buffalo Spirit, whose work honors the women that made a difference in her life.

Indian Uprising Gallery: www.indianuprisinggallery.com

Terrance Guardipee is represented by Catherine Black Horse at Black Horse Studio LLC: www.terranceguardipee.com

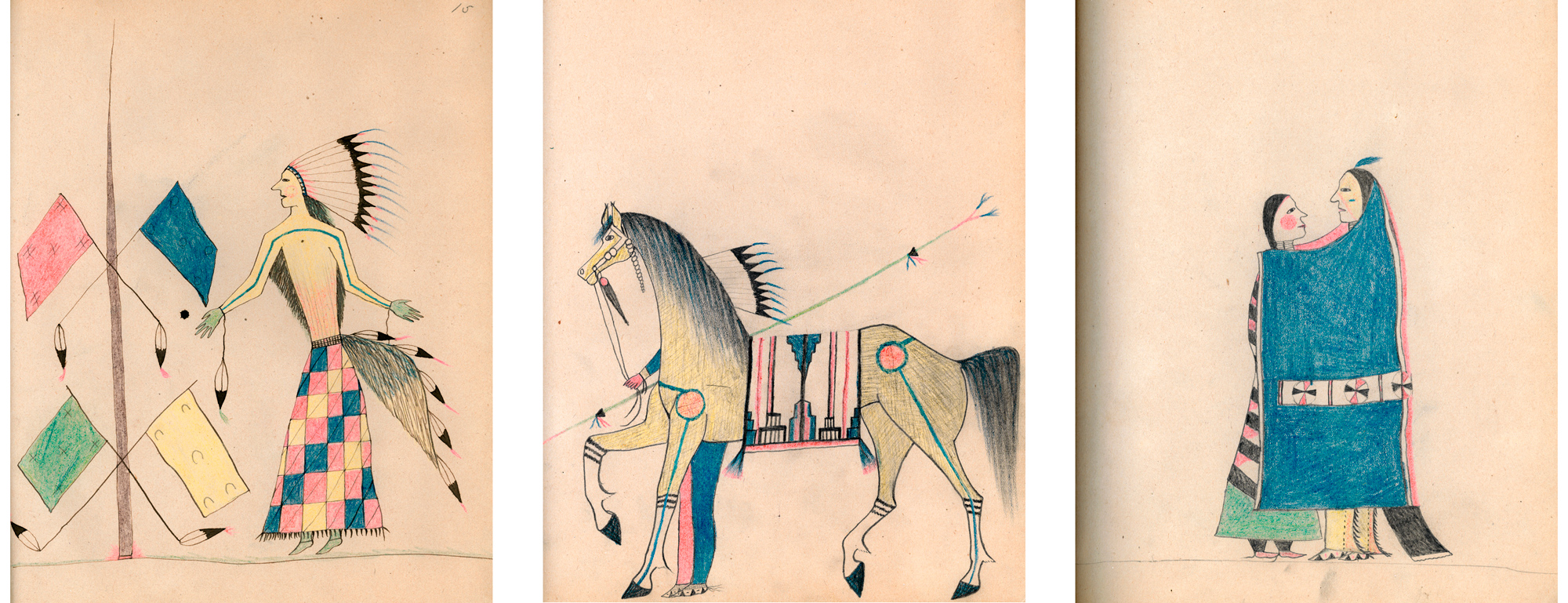

- Untitled Ledger Drawing | Walter Bone Shirt | 1890’s • These images are part of the 18-piece ledger collection that was donated to the University of Montana’s Mansfield Library in 1962 by Genevieve Prochnow. Mrs. Prochnow’s father, John S. Parke, probably acquired the ledger while serving as Assistant Adjutant General of Command at Rosebud Agency during the winter of 1890-1891. Experts have identified these drawings as being the work of Walter Bone Shirt, a Brule Lakota artist. Though a number of Bone Shirt drawings exist in private collections, consultants have indicated the 18 images in this ledger may be the only Walter Bone Shirts art available at a public institution. Due to the extremely fragile nature of the paper on which the drawings were made, the original ledger is available for viewing only by appointment.

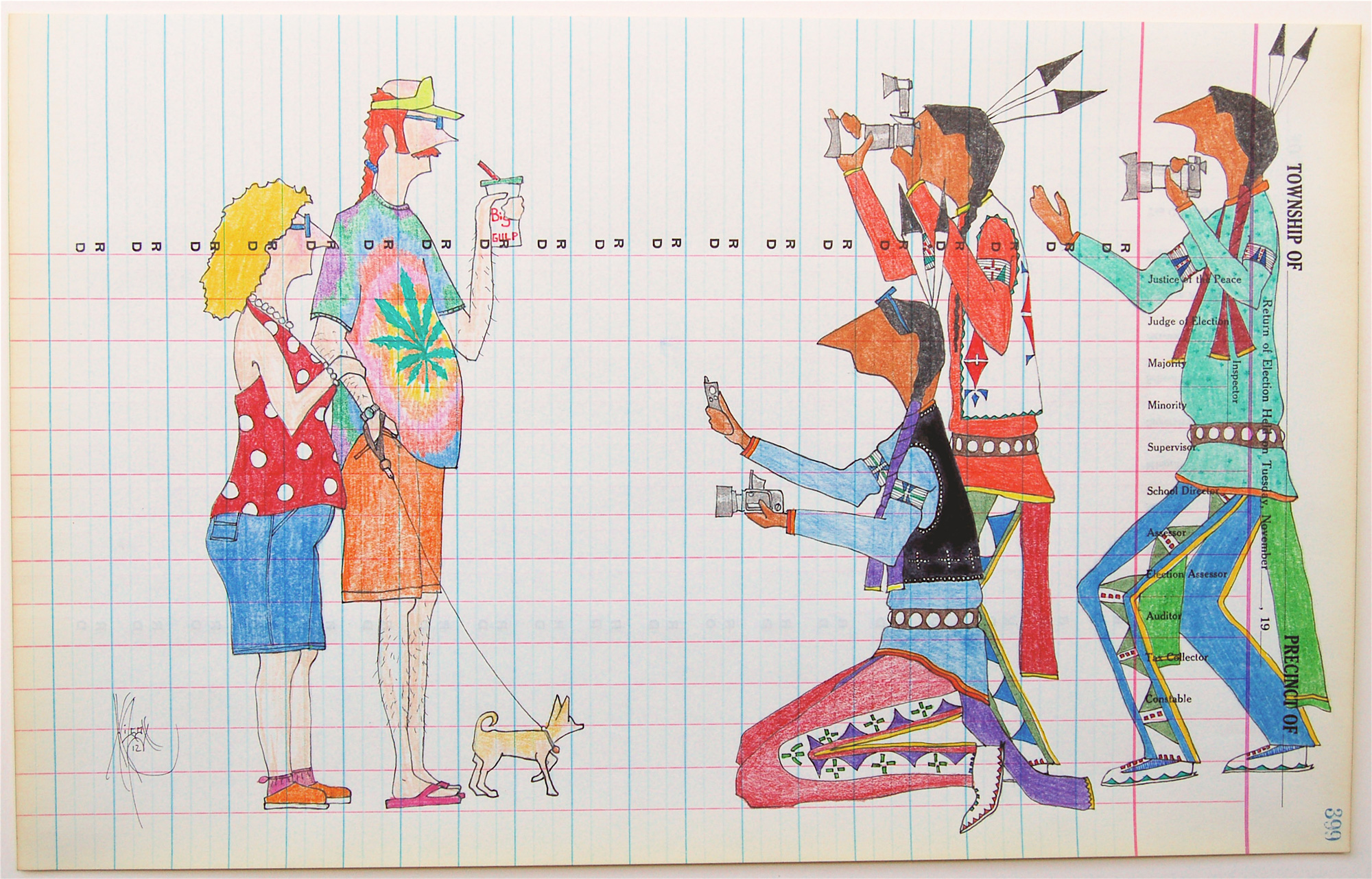

- “WOW! Full Blooded White People” | Color Pencil and Ink on Ledger Paper Dated 1936 | Dwayne Wilcox | 11″ x 17″ • Dwayne Wilcox started drawing role reversal images about 10 years ago. The inspiration for this piece came from 14 years of travel with a cultural exchange program that took adolescents from the reservation to the east coast for dance performances. He remembers when one kid waved and said “Bye Indians!” “I thought it was kind of strange to say good bye to someone and include their race. But they don’t know any better,” Wilcox said. “People come up and take pictures of you like you’re some kind of circus trick. Until you’re in that awkward position, you won’t be able to know.”

- “Sky Child Take the Bull” | Oil Colored Pencil on Ledger Documents | Terrance Guardipee | 32″ x 41″ • Terrance Guardipee, from the Blackfeet nation, draws inspiration from his heritage. He seeks to bring historic stories of his tribe back to life through his art. “I’m drawing from my ancestry and their war coup stories. I am taking what was happening then and making them contemporary by using bright colors, stylizing the horses, but also keeping the traditional symbols,” Guardipee said.

No Comments