23 Nov Local Knowledge: Uncovering Ancestral Narratives

On an autumn day in 1968, near the town of Wilsall in Montana’s Shields River Valley, two construction workers were using a backhoe when they dug up what appeared to be a grave. It was later identified as an ancient burial site that contained the remains of a young boy, along with more than 115 tools made of stone and antlers and dusted with red ochre. Archaeologists determined that the remains dated back some 12,600 years. It was the oldest such discovery in the country.

Fast forward to 2014, and Shane Doyle, a Bozeman, Montana-based historian for the Crow Nation, was called upon to serve as a research assistant and liaison between archaeologists, geneticists, and more than a dozen Montana Native American nations in the DNA sequencing and subsequent reburial of the boy. During the service, Doyle, who has studied the Northern Plains tribal style of music for more than 30 years, sang a heartfelt song to honor the life of this child, whom he considered a distant relative.

Doyle is an enrolled member of the Apsáalooke Nation (Crow Tribe).

“This boy was [initially] buried during a time when they were hunting woolly mammoths and fending off short-faced bears and saber-toothed tigers,” Doyle says, “so these [tools he was buried with] were items they badly needed.” He explains that burying a body with such crucial weapons and tools was a display of love and respect. And as a father to five kids, this family’s love for their son really hit home for Doyle. It also served as an example of how important family is to the Plains Indians, a value that remains true today for the Crow people.

Doyle grew up on the banks of the Bighorn River in Crow Agency, a Montana town located about an hour southeast of Billings in the northeast corner of the Crow reservation. He’s an enrolled member of the Apsáalooke Nation (Crow Tribe) and a soft-spoken, humble man who often closes his eyes to think while he speaks. After high school, Doyle attended Montana State University (MSU), where he began singing with his uncle, Conrad Fisher, as part of the Indian Club’s intertribal drum group. He also began to reconnect with tribal culture — both his own and that of his friends.

Part of Doyle’s studies as a historian for the Crow Nation focus on what the Crow people have lost through colonization, in hopes that he can help revive some of these traditions for future generations.

Doyle moved back to the Crow reservation, teaching fourth and fifth grades, before returning to MSU, where he earned a master’s degree in Native American studies and a doctorate in curriculum and instruction. He later founded Native Nexus, an educational-cultural consulting company, and worked with MSU and public schools to arrange for students to travel to reservations during the summer, where they would stay in tipis, visit sacred sites, and hear from tribal elders and community members. Later, Doyle completed a postdoctoral appointment in genetics with the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

As a historian for the Crow Nation, a lot of what Doyle seeks to uncover has been erased. “I feel like the character in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness who looks at that white spot on the map and says, ‘I have to go there, I have to find out what’s there.’”

Doyle’s ceremonial attire includes these traditional beaded cuffs.

Something he continues to study is what the Crow people have lost through colonization — and the effects of these losses. From 1851 to 1888, the U.S. government broke its treaties and took 90 percent of the Crows’ original reservation, which once began in southern Wyoming and comprised almost all of Montana, including the Awaxaawippíia (pronounced a-wuh-kaw-wah-pee-uh), now known to many as the Crazy Mountains, due to the range’s unpredictable weather and unrelenting terrain. Doyle has spent much time fasting and hiking in these mountains, carrying on a tradition from his ancestors and feeling a sense of connection to them there.

A lot of what Doyle seeks to understand through his work is how to sustain his ancestors’ mythological and spiritual connection to these sacred lands — to the mountains, streams, and valleys where, for centuries, his people have fasted in ceremony — and how to nourish the spiritual strength of his people so that they’re able to survive. “We need to get back to where we were, through hard work and sacrifice, by believing in who we are,” Doyle says. “And that’s what spending time in the Crazy Mountains is all about.”

This hand-beaded vest displays Doyle’s traditional Apsáalooke name.

The Awaxaawippíia are part of who Doyle’s family is today, part of how his family and the Crow people pass their traditional culture on to new generations. “Crows are resilient,” he says. “But we’ve seen better days. We have a long way to go to get back to where we were, but I’m hopeful that we can do so.” And a big part of this is through traditional ceremonies. “The beautiful thing about a ceremony is that you can be healed in an instant,” he says.

Last January, Doyle moderated a panel discussion after the screening of the documentary “Awaxaawippíia” at the Museum of the Rockies, wherein tribal members and officials discussed the significance to Native Americans of the Crazy Mountains and other public lands in Montana. The Montana Wilderness Association produced the film in partnership with Doyle, and he has also been serving as a liaison between the Crow and the Forest Service, in an attempt to protect these mountains from road building and development. “In an ideal world,” he says. “We would maintain the sanctity of sites like the Awaxaawippíia Crazy Mountains, which have proven over the years to be prominent in our ceremonial way of life.”

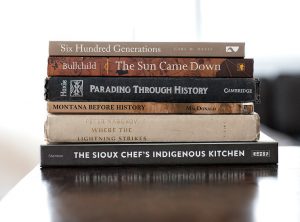

Doyle draws knowledge and inspiration from a number of books that are stacked around his home.

Doyle and his wife Megkian, a director for the Bighorn Valley Health Center, keep busy with their five kids, who range in age from 7 to 16 and all dance in traditional powwows. “Other than going to the reservation,” Doyle says, “this is the best way for them to practice their culture.” His boys have long hair, and it’s not uncommon in Bozeman for people to mistake them for girls, which he says would never happen on a reservation. “But all of my kids see themselves as multicultural, and I don’t think they see that as being strange or hard right now,” he says.

Doyle is also deeply committed to distance running. “Running gives me a rebirth every day, keeps my body healthy, and my mind clear,” he says. “I’ve finished the Missoula Marathon and the Bridger Ridge Run a few times each, and now my goal is to run the Boston Marathon. I’m just trying to be the best I can be. This is the Crow tradition.”

No Comments