25 Jul Local Knowledge: The Spirit of the Trees

If you think about it, trees are such an iconic part of nature; in many ways they are the mascot for the natural world. They stand tall, proud, and strong even while exposed to the harshest of elements. And these elements shape them, give them each their own individual scars, personalities, and spirit, if you will.

When Helena, Montana-based woodworker Timothy Carney cuts into a piece of hardwood, each with patterns of grain as unique as an individual’s fingerprints, it’s the personality and spirit he connects with. “My job as a worker of wood is to do my best to see the spirit and beauty in the wood and let it show through,” says Carney, whose furniture is made from live-edge slabs — the natural edges of a tree. “The live edge is a powerful reminder that this wood is from a living tree that was once anchored in the earth and reached to the sky … It endured storms, droughts, floods, and witnessed all manners of life around it.”

And when Carney makes that first cut, he doesn’t always have a plan; sometimes it starts with the wood, sometimes with an idea. “When I see this,” he says pointing to the-swirled-grain lines highlighted in a finished piece, “it’s totally in the rough. The design doesn’t occur to me right off the bat, but once I cut into it, I get the vision, the wood speaks to me or I tune into it.”

Carney doesn’t hide the flaws that come from a life well lived: the holes, the scars, the gnarls, the lines carved by insects. Actually, he doesn’t see them as flaws at all, but more like part of nature’s artwork that deserves to be accentuated. “In one piece, I was working with the wounded part of the tree that had dry rot in it, and it was a real mess,” Carney explains. “To me I saw beauty in that; when you work with that and repair it, it’s all that much more beautiful because of the wound.”

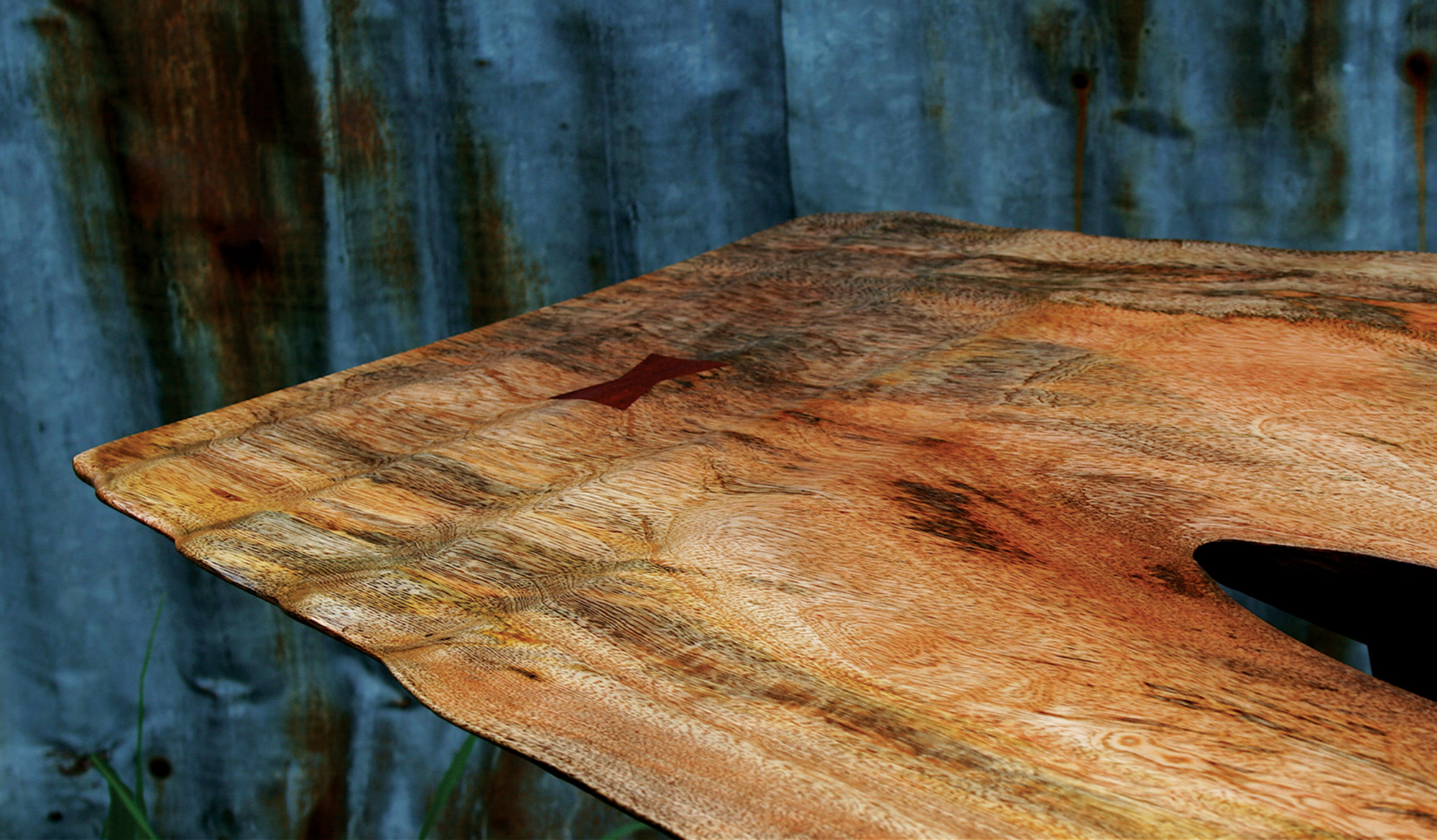

A good example is a hall/sofa table called The Yellowstone, made from curly mango wood with a mahogany and padauk wood base (his table bases are works of art in themselves). After cutting into the live slab, Carney saw waves in the grains, islands where the holes and knots naturally lay, and he thought of the Yellowstone River. He incorporated the holes and added to the river effect with carved ripples on one end.

“Every once in a while someone will look at a table with a hole in it, and they are puzzled,” says Carney’s wife, artist Maureen Shaughnessy. “But in reality, he designed the table to highlight that hole.”

The Madison, on the other hand, is a dining room table that was created very consciously. Starting with a sketched design, Carney had to find the right slab at a local hardwoods shop to fit his vision. “I may sketch out a design, but that can certainly change in the process,” he says. Once he added the finish and the grain of the wood popped, he saw a shallow river with small ripples, like the Madison River.

One of Carney’s woodworking idols is Sam Maloof, best known for his smooth, sculpted designs. Carney had the great pleasure of guidance from Maloof at a workshop, and has since created his own line of Maloof-style rocking chairs, adding his own personal touches. “As far as chairs go, so many might be beautiful, but not comfortable, and I think they have to be both,” he says.

Other Carney pieces take on a unique look depending on the designs nature handed them. One rocker is made from spotted wood that reminds him of Aboriginal dreamtime paintings. River’s Rift, a coffee table made from curly walnut and bloodwood, was crafted from two slabs that are turned inward with the live edges on the interior, creating an opening that reminded Carney of a canyon.

Carney started working with wood as a child growing up in Boise, Idaho. “When I was very small, I went down to the basement to make a box for scrap wood. By the time I got done, we had no more scrap wood,” he laughs.

He eventually majored in art and printmaking at Idaho State University, and when he got married and started a family, he worked as a carpenter for the railroad to make a living until getting laid off in the recession of 1982. He’d always made furniture on the side, but this was his chance to pursue it full time.

Over the years, live edge has become Carney’s signature, but he’s certainly not the first or the last to incorporate this natural aesthetic into a piece of furniture. Woodworker George Nakashima was working with live-edge slabs in the 1930s, and today it’s trendy; live-edge furniture complements both contemporary and rustic designs. “Tim’s been doing it for 40 years,” Shaughnessy says.

Carney describes his style as “urban organic,” more contemporary but brought to you by nature. Bringing out the spirit of the tree, his tables and chairs would fit into a lodge home in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, just as well as they would fit in a loft in New York City.

Carney’s work is labor intensive to say the least, and one rocking chair can take more than 80 hours to construct. “It can be monotonous and sometimes very meditative,” he says. “But once I put the finish on, it springs to life.” And through that life, he hopes to help people connect to nature, to connect with the spirit that he sees in the trees.

“I think people would sit down at a table like this,” he says of The Madison, “and they’d get a big smile on their faces. They’d connect to the piece, to the spirit of it, to nature, and they may not even know why it makes them feel happy, it just does.”

Editor’s Note: Carney’s work is on display at 1 + 1 = 1 Gallery on Last Chance Gulch in Helena, Montana, and can be seen online at timothyswoodworking.com.

- “Maureen’s Stool” made of cherry and quilted birch.

- A walnut, live-edge coffee table and rocker.

- A hall table made of curly maple and ebonized cherry.

- “Tipsy,” a wine rack made of cherry and bloodwood.

- “The Yellowstone” hall table, made of curly mango, paduak, mahogany, and lacewood.

- “River’s Rift” curly walnut and Bloodwood

- Tim Carney works on two aspen leaf-shaped end tables for the upcoming “Elements” exhibit at 1+1=1 Gallery in Helena.

- Carney carved a ripple into the end of the live-edge slab of “The Yellowstone” hall table to evoke the water surface of the Yellowstone River.

- “The Madison” | Spalted Curly Maple and Black Walnut

- “Maureen’s Rocker,” made of walnut and birdseye maple.

- “Dreamtime Rocker” | Lacewood and Curly Maple

No Comments