24 Nov Local Knowledge: Natural Wonder

Some 20 years ago, I met David Quammen under unusual circumstances. He had written an essay about cougars for a wilderness advocacy publication to which I subscribed. The piece included some disparaging comments about cougar hunting, largely based on the assumption that lion hunters are only interested in trophies and don’t eat what they shoot. I contacted the editor, told him that the author hadn’t researched the piece adequately, and that I eat every cougar I choose to shoot. To his credit, Quammen contacted me, acknowledged my point, and asked me to take him hunting so he could learn more about it. The result was two cold days in the mountains, the realization that we had a surprising amount in common, and a mountain lion dinner. We have been friends ever since.

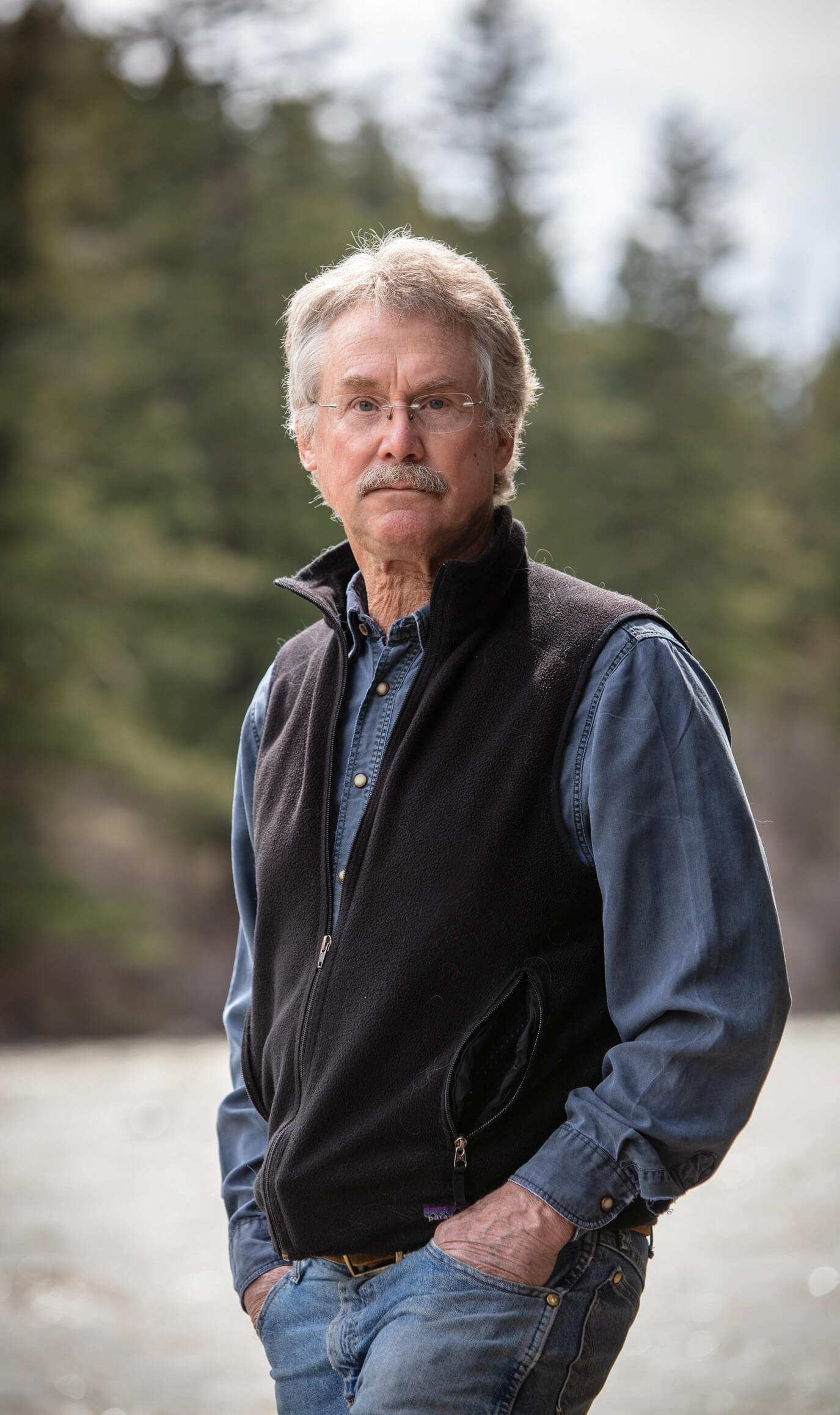

With output as impressive as the quality of his writing, David Quammen writes books that are comprehensive, informative, and enjoyable to read. Photographed by DON & LORI THOMAS

Don’t worry — this piece is not about hunting (or eating) mountain lions. It’s a profile of a writer whose energy and acumen stand out even in a community with a remarkably high per capita population of creative people. Quammen is engaging, articulate, and passionate about writing and the subjects he writes about. His ability to make others comfortable and eager to talk helps explain why so many busy people are willing to give him their time during long, in-depth interviews.

He spent his childhood in suburban Cincinnati, where he indulged an early fascination with nature by exploring a mature hardwood forest behind his family home. He describes this time as an “iconic experience” and still mourns its loss to development. Growing up in a Catholic family, he enjoyed the advantages of a Jesuit prep school education. He still remembers his senior year English teacher, who encouraged his initial interest in writing. At the time, he’d been applying to several Catholic colleges when that teacher suggested he apply to Yale because it had what he considered the best English department in the country.

Quammen did wind up at Yale, where he established friendships with several well-known writers, including Robert Penn Warren, Pulitzer-Prize- winning author of All the King’s Men, among other literary accomplishments. With encouragement from Penn Warren and writer William Buckley, Quammen published his first novel, To Walk the Line, based on his formative experiences in 1968 as a Chicago community organizer “before Barack Obama made it fashionable.” The book was released by a major New York publisher just as its author graduated from college. “I’m not ashamed of it, but I’m not proud of it either,” he says. “It was early work by a 20-year-old.”

Penn Warren also encouraged Quammen to apply for a Rhodes Scholarship. He did so successfully and spent two years studying English at Oxford, where he completed a thesis on William Faulkner. While Quammen feels ambivalent about the rigid formality he encountered at Oxford, he speaks highly of his teachers and the quality of his education in England. Yet, how did Quammen become one of the country’s leading science writers with no formal background in science?

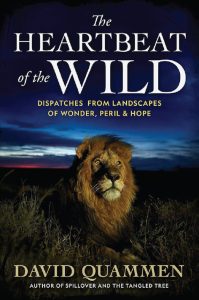

Quammen’s latest, Heartbeat of the Wild, includes essays from his travels to some of the world’s wildest places and examines the conflicts that can arise between wildlife and people. Photographed by RONAN DONOVAN

“I had great English teachers but no great biology teachers,” he says. “I had always been fascinated by both nature and writing. I wasn’t precocious. Just motivated.”

After studying at Oxford, Quammen came to Montana in 1973 because “I wanted to be close to the ground.” He worked as a bartender, audited some zoology classes in Missoula, and, eventually, guided fly-fishing trips on the Smith and Big Hole rivers.

Most of his formal English studies had focused on fiction, but around this time he began to read a lot of nonfiction, ranging from classical writers like Herodotus to contemporaries such as Stephen Jay Gould. Charles Darwin’s life and work particularly intrigued Quammen, as reflected in his 2007 book The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution. These writers made him realize that he “could make art out of nonfiction,” which he then proceeded to do.

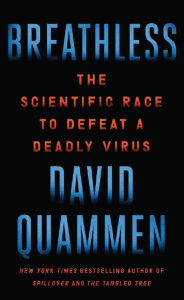

In 1981, he began turning his fascination with nature into regular columns for Outside magazine, many of which were included in his first nonfiction books, Natural Acts: A Sidelong View of Science and Nature (1985) and The Flight of the Iguana: A Sidelong View of Science and Nature (1988). Quammen has published a total of 18 books, including 2022’s timely Breathless: The Scientific Race to Defeat a Deadly Virus, a detailed study of the COVID pandemic and Quammen’s personal favorite to date, for which he was chosen as a finalist for the nonfiction National Book Award.

His most recent book, Heartbeat of the Wild: Dispatches from Landscapes of Wonder, Peril, and Hope, was published by National Geographic in May of 2023 and is a collection of essays about his travels to fascinating destinations around the world. Quammen has traveled to many interesting places: He loved Tasmania, where he engaged in field research on Tasmanian devils (the world’s only surviving carnivorous marsupial), and Madagascar because of its unique biological diversity. His favorite travel memories, however, derive from a long expedition on foot through the jungles of central Africa. He describes his National Geographic-sponsored MegaTransect journey through the forest as awe-inspiring and unforgettable. He also fondly reminisces about an encounter with a herd of galloping giraffes while on assignment off the beaten path in the Serengeti.

Interestingly, before moving to Montana, Quammen explored the state’s attractions through the eyes of other writers and artists. In 1982, a New York-based magazine assigned a story to him about why so many creative talents were ending up in Montana, so he posed the question to a list of writers, including Norman Maclean, James Welsh, Thomas McGuane, and the perhaps lesser-known Max Crawford, author of Lords of the Plain, who suggested it was due to “the exchange rate.” Unlikely as it may seem now, Montana was still a bargain for creative people without day jobs. The piece ran under the title “Montana: A Cheap Hideout for Writers.”

While those days may be gone, Quammen believes that Montana is still a good draw for writers, artists, and photographers who can live wherever they want while enjoying Montana’s outdoor lifestyle, from mountains and skiing to scenery and fly fishing.

Quammen’s portfolio illustrates his ability to navigate difficult problems. Time and again, he presents complex scientific subjects to a readership of non-scientists. One of his earlier books, The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life, deals with the history of molecular phylogenetics, but Quammen admits being circumspect with his publisher about the intimidating topic. As he explains, for many readers, confronting a challenging subject is like going into the weeds, and part of his job is to convince them that going into the weeds doesn’t have to be unpleasant and can lead to great rewards.

Breathless is an excellent example of the ways Quammen distinguishes himself in popular science writing. He meticulously researched his facts, not just by reviewing published literature but by going directly to the scientists who produced it. He includes a remarkable amount of firsthand material obtained by interviews with numerous scientists prominent in a complex field that was changing by the day, including those working in China and other international locations. Pandemic travel restrictions made this especially difficult, a problem neatly solved by Zoom.

Despite these challenges, Quammen manages to portray the scientists he interviewed not just as data generators but as real people. Because of the virus’s geographic origins, many of them were Chinese. He found them forthcoming, although he recognized they were facing restrictions on what they were allowed to say. He devotes considerable time to exploring nagging questions about the origins of the virus, and openly regrets the politicization of the issue here in America. Certainly, his opinions are based on rigorous analysis of peer-reviewed data rather than politics.

Some of Quammen’s regular readers may find Breathless more difficult than his earlier works. After all, its subjects are sub-microscopic RNA fragments rather than large, charismatic animals. However, we will be discussing the pandemic, along with our bungling and triumphs, for years to come. Breathless should prove invaluable during that process, especially for future generations who didn’t witness the pandemic firsthand.

After moving to Bozeman in 1984, Quammen purchased an old house on a nicely located lot in an old part of town. When he realized that he liked the property more than the house, he replaced it with a newer version, where he now lives with his wife, Betsy, another writer. She is particularly interested in debunking entrenched but inaccurate myths about the West, as explored in her first book, American Zion: Cliven Bundy, God & Public Lands in the West. She addresses similar themes in her latest, True West: Myth and Mending on the Far Side of America.

Deep in the weeds himself, Quammen is a force in science and nature writing. I can only summarize this profile in one way: Read the books.

A central Montana resident since 1973, E. Donnall Thomas Jr. has been everything from a physician to a bear hunting guide in Alaska. He writes about the outdoors for numerous publications and lives in Lewistown, Montana with his wife, Lori, and their bird dogs.

No Comments