03 Feb Local Knowledge: David Stuver’s Familiar Waters

Many anglers have likely discovered that even though we’re the ones casting a fly, it’s the trout that hooks us. When this happens, the sport becomes not just a game, but a passion. For angler David Stuver, it also turned into a lifetime of education.

Stuver was 22 years old the first time he cast a fly into Montana waters. The year was 1963, and although he’d spent the first part of his life fishing near his family’s ranch along the Powder River in the southeastern part of the state, he’d only used bait, catching catfish and sauger with earthworms. While the ranch is still operated by his brother, Stuver left for a different calling at a young age. After earning a bachelor’s degree in agricultural science from Montana State University, he began a career with the Department of Agriculture in Helena. On the side, he worked as a fly-fishing guide for more than a decade.

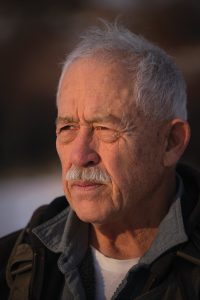

David Stuver prepares for a wintry day of fly fishing on his home stretch of Big Spring Creek near Lewistown, Montana.

If Stuver was streamside with you, and you turned to ask him what the single most important aspect of the sport was, he would smile from the corner of his mouth and say that it’s to learn, adding, “To be successful, one needs to adapt.” Adapting requires forgetting what you thought you knew and learning something different. This is particularly true in today’s waters, which are experiencing higher fishing pressure than ever before. “Trout have become more wary,” says Stuver, “so anglers need to become more knowledgeable. Taking the time to learn the craft of fly fishing will pay off in results.”

These results are not only calculated by fish size and counts, but also something less tangible: the sensation of being immersed in a natural landscape, and the realization that no matter how much we learn, we can still be fooled by a little fish. As Stuver remarks, “If catching fish is your only objective, you’re either new to the game or too focused on measurable results.” So, we continue to learn.

Stuver studies the water before determining what fly to use, where to stand, and which direction to cast.

When Stuver attended university in Bozeman, he spent much of his time standing waist-deep in the rivers and streams around the Gallatin Valley. “At that time, the majority of spring creeks were on private ranches, but the farmers allowed you to fish. It was common to catch trout over 3 pounds, and now we’re happy with an 18-incher,” Stuver says, explaining that he believes the rivers are still capable of producing larger fish, and the water quality is even better than it was 40 or 50 years ago. “Montana has stricter regulations now. It used to be that many small towns released their sewage effluent directly into streams, but this has changed,” he says, adding that “there are also new laws to control irrigation, which has resulted in better water quality and quantity for trout.”

Stuver sees more positives than negatives in today’s fly-fishing scene and notes that the greatest challenge for modern anglers is the fact that there are simply more of us. Rarely when one is sitting at home dreaming about a day on the river does that imagery include other anglers in the periphery. Yet that has become the reality on many of Montana’s trout waters. Sure, there are still plenty of places to escape the crowds and cast to fish that rarely see artificial flies, but we don’t always have the time or ability to reach them. So as anglers, we must adapt our tactics for trout that have become ever more suspicious.

This provides a new arena of education for the contemporary angler. Stuver has spent 60 years of his life fly fishing the high-elevation streams, spring creeks, prairie ponds, and larger blue-ribbon rivers of Montana; having experienced the changes firsthand, he reminds us, once again, to be adaptable. “This requires research and patience, and is not intended for those seeking instant gratification,” he warns. Stuver has found that fly patterns that worked in decades past have become less successful, resulting in more realistic ones. “Still, presentation is more important than pattern,” he says, explaining that you’re more likely to attract a trout to an imperfect fly than to an imperfect drift.

Once he’s at the river, Stuver always takes a few moments to observe the landscape and water prior to wetting a line. Even at streams he’s fished for decades (with detailed journal entries about specific hatches that took place there), he will first study the shoreline to look for insects, watch the water for signs of feeding fish — both on the surface and beneath — and observe the current to understand where the trout might lie. To play this sport is to learn the environment where trout live, he says.

After Stuver has selected a fly pattern and the run he intends to fish, he determines a safe place to cast. The first consideration is the casting alley: Will there be room for a backcast? Will it be better to use a sidearm, slingshot, roll, or another specialty cast? He considers it paramount that a cast does not spook the fish, and that it’s positioned in the flow to provide a natural drift. “When anglers become frustrated by not catching fish, they will often change their fly every five minutes,” he says. “More often than not, the fly is not the problem, but rather their cast has spooked the fish, or their drift has unnatural drag.”

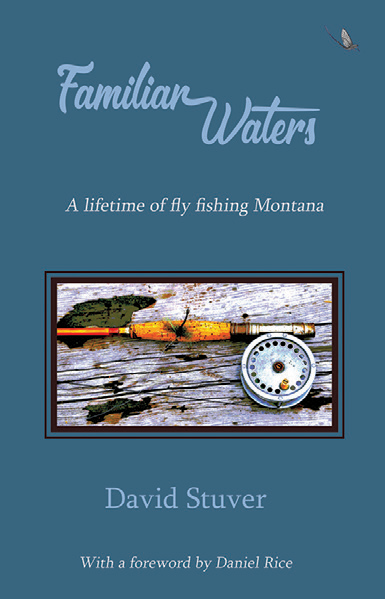

When we pick up that fly rod and go to the river — whether alone, with friends, or accompanied by a hired guide — we know that there is still much to learn. Or as Stuver says, “Experience does not equal expertise.” Perhaps, at its source, fly fishing is designed to be a humbling experience. We are humbled by the sight of sharp mountain peaks, by the touch of cold pristine water, and by the fact that we will never know it all. When we are humbled by these things, we discover an urge to learn and find the clarity to experience the environment around us. Through these experiences and environments, the passion for fly fishing grows. As Stuver shares in the last line of his 2020 book, Familiar Waters: A Lifetime of Fly Fishing Montana (Riverfeet Press): “It is time to enjoy the soft classical tones of riffles and birds common to a trout stream.”

Daniel J. Rice has been casting flies for over 30 years. The founder of Riverfeet Press and author of The Unpeopled Season and This Side of a Wilderness, Rice has worked as a hydrographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and as the sales manager of fly fishing trips for Montana Angler; www.riverfeetpress.

Erik Petersen has been a Montana-based photographer and filmmaker for the past two decades. He lives in Livingston and loves getting his two sons and two bird dogs outdoors; erikpetersenphoto.com.

No Comments