15 Feb Local Knowledge: Conservation is a Circus Act

The first thing I notice about Montana conservationist and sportsman Rock Ringling is that he throws a tight loop. Spend a lifetime fly fishing and you develop an appreciation for these things. It is instinctive and, if you are at all competitive, it will start that burn. It is when Ringling switches to his other hand and throws an equally pretty cast on a particularly tight bend that a right-hander like me cannot reach very well, that I realize the guy is going to outfish me. Or at least outcast me. With either hand.

We are standing on the banks of the Ruby River with the Tobacco Roots on the eastern skyline and the Ruby range at our backs. On my dawn drive to meet Ringling on this wide-sky day, I saw a cow and a calf moose standing midcurrent, a good whitetail buck, a half-dozen wild turkeys, and a rooster pheasant. I tell myself that even if I get outdone, my ego will survive on a day that starts out like this one has.

The Ruby — and the wildlife and fish that call the valley home — owes its wide-open character in no small part to the man I am fishing with today. Just upstream from our eddy is one of the crown jewels of the valley, the Woodson Ranch, a stunning property cleaved by the Ruby’s meanders, and forever protected by the Montana Land Reliance, one of the state’s leading land trusts. Ringling, as one of the directors of the Land Reliance, helped save the Woodson forever.

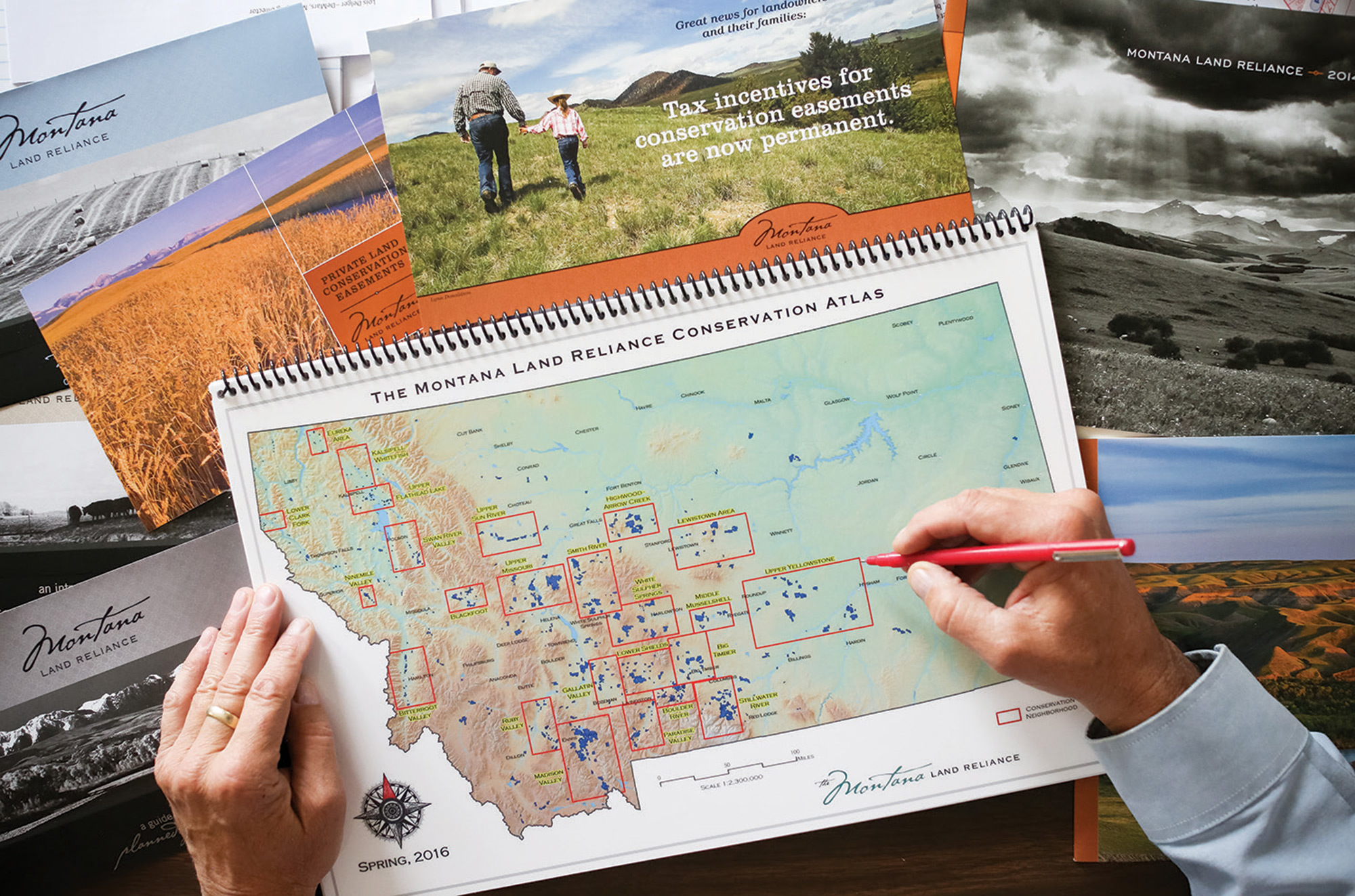

For nearly three decades, Ringling and the Land Reliance, through their conservation easements, have been keeping Montana ranches and farmlands, and the rivers and streams that flow through them, protected from development. One million acres and 1,600 miles of river and stream have been protected in Ringling’s tenure. It is quite a legacy, and we talk about it as we leapfrog upstream in the growing day. But mostly we talk about fishing and the state we love.

“When I was a kid growing up in White Sulphur Springs, I had the run of the country. The Smith. Duck Creek. Sheep Creek. Whitetail Creek,” he says. “But it wasn’t until I went to college in Bozeman that I really got into fly fishing. Bozeman in 1969 was an ag town, and we had all the spring creeks and the Gallatin. We just went everywhere.”

Now in his sixties, Ringling moves in the river with an athletic ease that is bound to be genetic. His great-grandfather, Alf T. Ringling, was one of the five founding brothers of Ringling Brothers Circus in 1884. Though never active in the circus himself (his father left the business after the second World War), it’s easy to imagine that Ringling’s streamside gymnastics and his graceful, ambidextrous casts come from a family predisposition.

The kinked Ruby bends back on itself — we walk a mile to move an inch — and we cast streamers and nymphs into the slightly off-color water. Fishing beside us is Gusty Clarke, a young lady who works with Ringling and who throws a damned fine loop as well. Mixed in with Ringling’s stories of fishing and growing up Montana, he ladles a typically-Western brand of teasing onto Clarke, fondly chiding her for missing a rise or snagging a backcast in a recalcitrant willow. But I can tell his banter is the kind that is dosed out to someone he considers a protégé, or perhaps a granddaughter. When I rib Ringling about how supportive he is of his junior employees, Clarke just good-naturedly laughs it off. And then catches the first trout of the day.

Leap-frogging and casting. Talking. Fishing is slow, but Ringling pins into one, a nice brown that fights hard against the rod-lift — in Ringling’s left hand now — and is released quickly.

A ranch kid raised by a father and mother who valued wildlife and big country and, particularly, the birdlife of the high prairies, Ringling is a Montanan to his core. He has rodeoed, castrated livestock, and learned to drive at the wheel of a tractor. He knows everyone and seemingly everyone is related to him. The late novelist Ivan Doig was a famous cousin. Ringling’s dad, well into his 90s now, is still running the ranch in Carter County. The Ringlings were a fixture in the heart of early Montana, managing a massive ranch, raising sheep, and running the famous circus. In the 1960s, Ringling’s immediate family left White Sulphur for a ranch outside Springdale on the Yellowstone. A big river was at his doorstep.

“I can remember fishing for whitefish and getting paid a penny a fish by this old guy who used to smoke them and sell them,” says Ringling. “We caught them on maggots. We caught brook trout, brown trout, everything. We fished in the Crazies, everywhere.”

The family moved again, to Southeastern Montana and the town of Ekalaka and another big ranch where trout streams were far away but sage and sharptail grouse and antelope abundant. Then college and more rivers and streams and the obsession that is fly fishing. After college, that passion for Montana and fishing became a job with the Land Reliance. And that job included taking fishing trips with donors: all over Montana, to British Columbia (where Ringling took up spey casting and steelhead), to the Gulf for redfish, and the tropics for bonefish.

“I suppose I fish about 100 days a year,” he says. I think how it is that the best jobs are those where passions are turned into professions.

Ringling had not been at his job long when “The Movie” came out. The movie, of course, was the 1992 production “A River Runs Through It,” the one pivotal event that everyone who loves Montana can point to as when the state got discovered and changed, for better or worse. In the conservation easement business, the film created new challenges as newcomers came to the state. Some had a deep passion for fishing, for Montana, and for taking care of the land. Others wanted to make a few dollars and move on. Ringling came up with a now well-known slogan for the Land Reliance: Cows not Condos.

“We found that a lot of people who came from the coasts, particularly the East Coast, had this love of the land,” remembers Ringling. “We were able to tap into that.”

New landowners worked more and more with the Land Reliance, Ringling, and his partners to protect what makes Montana, Montana. Multigenerational ranches and farms got into the game too, wanting to leave their lifestyle and intact property to their descendants. Conservation easements are agreements between the landowners and land trusts that protect the open nature of the land, and enable owners to pass on their heritage to their heirs. An easement allows the owner to get value from conservation, either through sale of the easement or a donation that may be deducted against taxes. Ringling was able to turn his love of fishing and the land — shared by many of the folks who saw the movie — into some key acquisitions throughout the state: fishing accesses and river bank protections on the Missouri, boat camp leases on the lower Smith, the banks of the Madison, the Ruby, the Yellowstone, and the Blackfoot saved as-is for future generations. Ringling was at the heart of those negotiations.

For all of the good he has done for fish and fishermen in Montana, he has left a national legacy as well with the December 2015 passage of a permanent tax relief bill that allows landowners across the nation to realize lasting benefits from conserving land. This was a bill that Ringling was instrumental in creating with a few other key conservationists, and that the Land Reliance pushed for and worked on for years. The Montana-grown bill eventually made its way onto the national stage with conservation benefits for farms and ranches across the country.

We talk about the bill as we fish. Ringling is deferential, giving credit to other managing partners at the nonprofit and people like House Majority Leader Paul Ryan, who helped pass the tax bill in the 114th Congress. “There’s just a lot of people who care about wildlife and fishing and agriculture,” says Ringling.

The three of us move up the stream as the sun starts to drop, slanting across the Ruby. Ringling catches the last fish of the day, a small rainbow, and kneels to release it. Then he stands and looks upriver where the Woodson Ranch lies beyond a few miles of willows. In that moment, I can’t help but think about how fishing and rivers bring people together and bind them with a common thread that extends out into life. Here is a grandson of The Greatest Show on Earth, and still-wild Montana is his life’s work. That’s a pretty good performance.

- Rock with a photo of his great-grandfather, Alf T. Ringling, and a boyhood portrait of his grandfather, Richard.

- Rock Ringling, one of three managing directors of the Montana Land Reliance, fishes on the Ruby River. Since its founding in 1978, the Land Reliance has conserved over 958,000 acres of Montana in more than 820 voluntary easement agreements.

- Rock Ringling’s great-grandfather, Alf T. Ringling, was one of founders of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Rock’s grandfather, Richard, and Richard’s uncle, John — the youngest of the Ringling Brothers — eventually settled in White Sulphur Springs.

- Among many other accomplishments in conservation, Ringling was the creator of the famous slogan, “Cows Not Condos.”

No Comments