13 Aug Joel Ostlind: Western Connections

THERE IS A SAYING ABOUT LIVING IN THE WEST, that it’s like one big Main Street, where the connection to just about everyone you meet is whittled down from 6 degrees to more like 2 or 3. So I was not completely surprised to learn that when artist Joel Ostlind looks out the window of his home in the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming, his view is of the ranch that my father worked on as a ranch hand back in 1969.

The Bighorn Valley is one of the more stunning parts of Wyoming, so it’s also not surprising that Ostlind credits much of his inspiration for becoming an artist to the fact that he lives here. But what is surprising is his initial inspiration. Ostlind grew up in Casper, and says he considers the area around there to be one of the prettiest parts of the West. “When I shared that with a friend of mine, he said, ‘You are probably the only person to ever say that,’” Ostlind states.

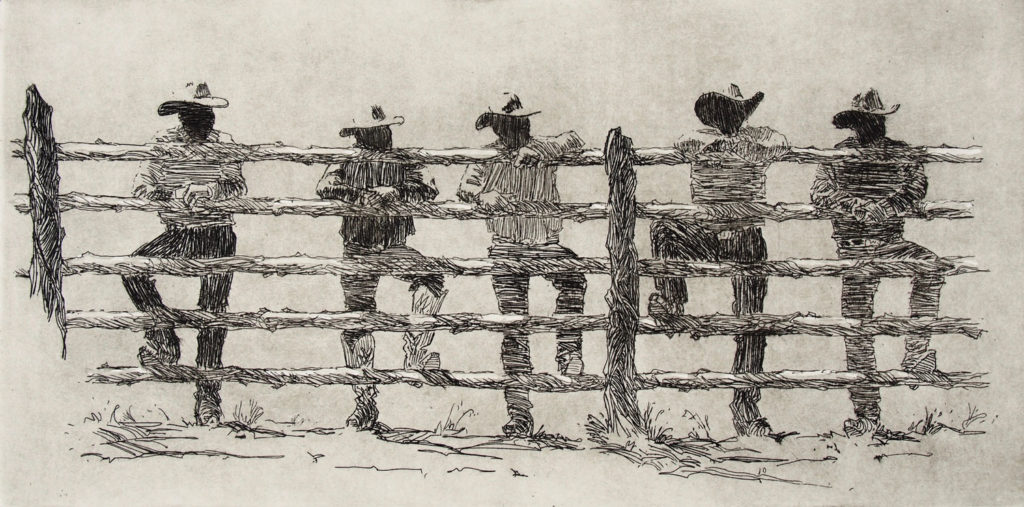

Infinite Wisdom | Etching | 5 x 10 inches

Natrona County is not known for its scenery, but it’s part of Ostlind’s makeup to capture the beauty wherever he finds himself. Ostlind first started acting on this fascination with the world around him when his parents gave him a sketchbook for Christmas when he was a young man working on a ranch in Texas. He started drawing scenes from the ranch, and found that he was pretty good at it. But more importantly, he couldn’t get enough of it.

Ostlind’s work reflects the places he grew up and lived, not only because they prominently feature cowboys, livestock, and wide-open country, but also because the colors are often muted, as befits the landscape of Wyoming in particular. “To me, the critical thing is the value of dark and light,” Ostlind says. Ken Schuster, who curated a recent show of Ostlind’s work at The Brinton Museum just outside of Sheridan, disagrees. “You think his colors are muted?” he says with a certain degree of surprise.

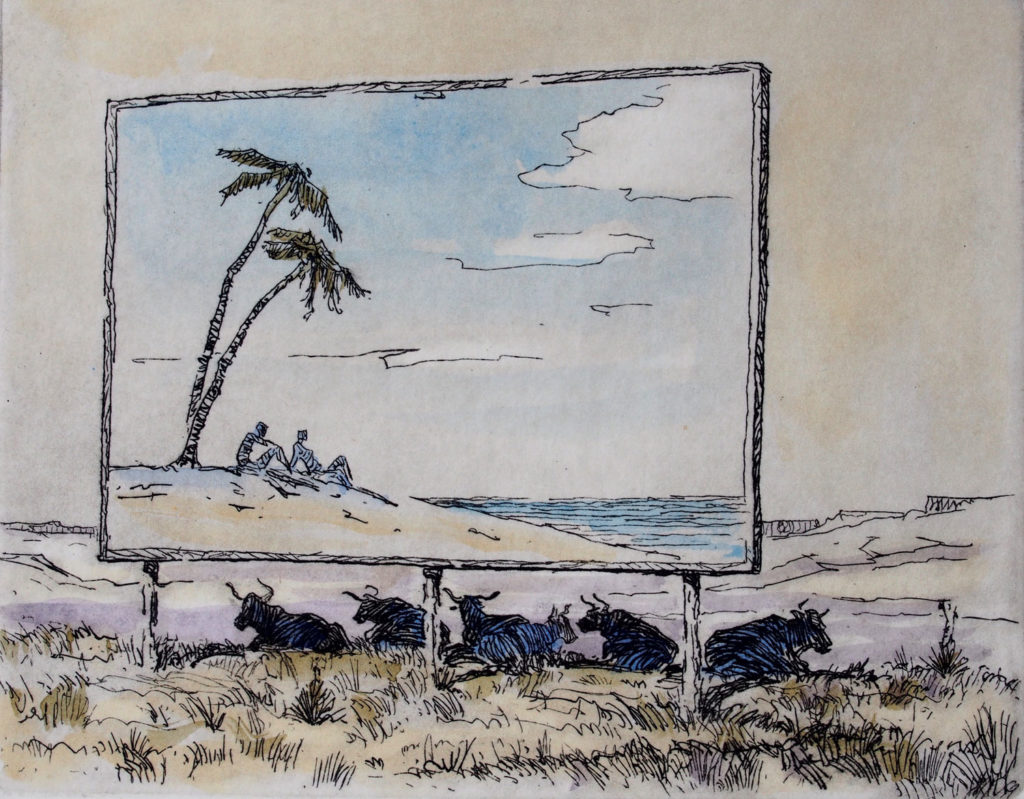

A Shore by the Sagebrush Sea | Etching with Watercolor | 4 x 5 inches

He makes me reassess my assessment, but yeah, a lot of Ostlind’s paintings feature soft yellows and browns. But when he does use color, as in a painting titled Morning Comes Over the Ridge, Ostlind’s colors explode from the canvas. This piece also emphasizes his earlier comment about dark and light, with the front half of the painting showing a wide expanse of land lost in the shadows of morning. But behind that, the mountains rise up, brought to their full glory by the sunlight.

Schuster puts Ostlind in the same category as two of his favorite Western artists, Hans Kleiber and Edward Borein, and it’s easy to see why. Both of these men specialized in paintings and etchings, and Schuster believes that etching is where Ostlind really shines. “He has worked hard on his painting in recent years, but printing has always been his biggest strength,” Schuster says. “He’s very good.”

Ostlind’s etchings often show his sense of humor, too, as with a piece called A Shore by the Sagebrush Sea, which features a few cows reclining beneath a billboard displaying two people lounging on a beach.

The Big House | Watercolor and Gouache | 5 x 9 inches

Not long after working in Texas, Ostlind moved back to Wyoming, where he took a job as a hand on the Padlock Ranch, which is just a few miles up the road from where he lives now. One day a film crew came to the ranch to shoot some Marlboro commercials, and Ostlind took the opportunity to show the art director a few of his sketches. “You’ve got something here,” the art director told him. “You should be doing more of this.”

This was the first time it occurred to Ostlind that he might be good. He started giving his drawings to friends, and eventually made a few sales. He has one memory of an early sale, when someone bought a painting of a ranch for $50. When he and his family were heading to town to cash the check, his daughter, about 6 years old at the time, tripped going out the door and cut her lip. When they got to town, they went to the doctor, who stitched up the cut. The cost was $50. “It’s a good story now, but that was a lot of money back then,” Ostlind says.

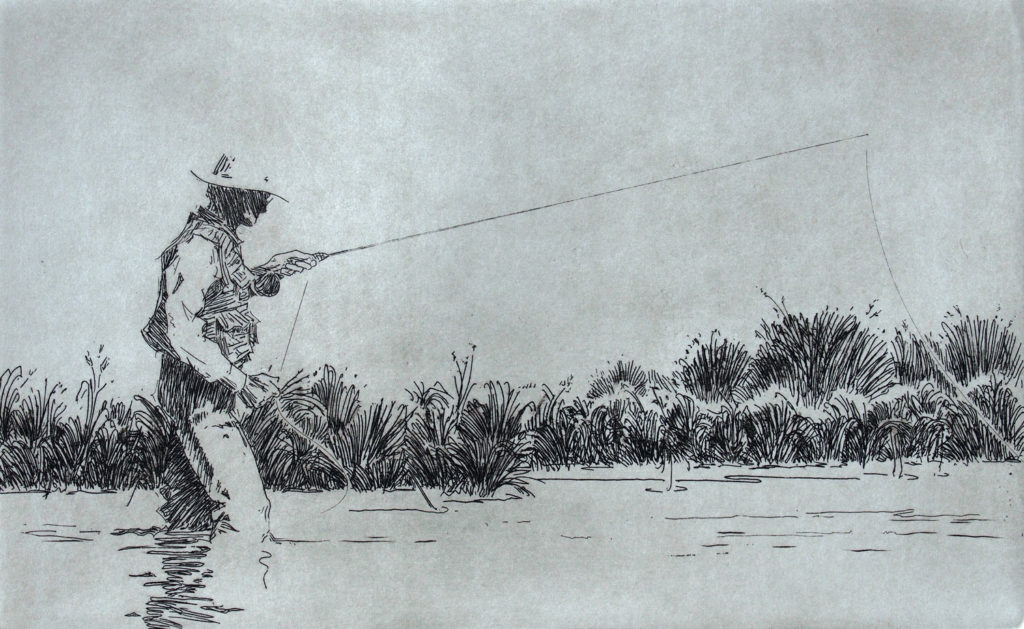

Believing in Nymphs | Etching | 5 x 8 inches

Ostlind took a couple of art classes in college, one in watercolor and one in design, but he is essentially self taught. He credits a book published in 1925 called The Art of Etching, by E.S. Lumsden, a Scottish artist who died in 1949, as his main source of inspiration. “I found that book a long time ago, and it’s basically my bible,” Ostlind says. Now at 65 years old, his cowboying days are behind him, and he’s happy to have his wife, a retired nurse, working as his framer. “She does a beautiful job with the framing. And she really seems to like it,” he says.

Despite his lack of training, Ostlind’s perseverance has led to bigger paychecks after that initial $50, and he has been represented by the Simpson Gallagher Gallery in Cody since its inception.

“I found out about Joel 26 years ago because Bob Barlow, a painter in Gillette, Wyoming, had met him through the Brinton Museum,” gallery owner Susan Gallagher recalls. “He thought Joel Ostlind was the next Edward Borein and one of the finest draftsmen he’d ever met.” In her years of representing his work, including many of his etchings, Gallagher has come to appreciate Ostlind as a purist and someone who has an appreciation for an ancient and classical art form. “I love what a creative person he is, and I also love his whimsy, willingness to try new things, and his commitment to his craft,” she adds. “I couldn’t be a bigger fan.”

No Comments