02 Aug In Pursuit of Perfection

Artist Joe Kronenberg doesn’t spend a lot of time reflecting on his past, but his studio is a repository for its hallmarks. There’s the Ralph “Tuffy” Berg Award for outstanding emerging artist that he received during the 2009 C.M. Russell Museum Auction; a framed reproduction of a painting by William-Adolphe Bouguereau, a 19th-century French master of classical realism, whose academic style informs Kronenberg’s approach to portraiture; and photos of Kronenberg’s children when they were toddlers and their father would sit at his drafting table in the family room, pouring over books on wildlife painting, trying to discern the artists’ secrets.

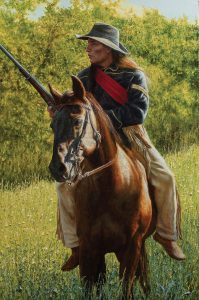

Emissary of the Plains | OIL | 42 X 28 INCHES

Kronenberg nurtured a love for art through his early childhood and adolescence in Spokane Valley, Washington. After graduating from high school, he enrolled in Spokane Falls Community College’s art program but says it focused on expression versus technique and wasn’t a good fit. Inside Kronenberg’s Spirit Lake, Idaho studio sits a curious reminder of that time: an object Kronenberg calls a “feelie.” Resembling Swiss cheese, the elegantly carved block of walnut is the abstract sculpture assignment from college that prompted Kronenberg to suspend his dreams of becoming a professional artist. “I kind of keep it around to remind me [to stay true to myself],” he says.

Realism, technique, and the Western genre interested Kronenberg most, and he fondly remembers his extended horseback trips into the backcountry with his stepfather. “We’d ride the horses bareback into the middle of the Clearwater [River] and fish off their backs,” he says. The lifestyle and mythology of the West offered an undeniable and intriguing appeal.

Being Brave | OIL | 30 X 24 INCHES

Even though he attended school with Indigenous students, Kronenberg says he lacked context as an adolescent. Tribal history and culture weren’t part of the public school curriculum until just a decade ago, after Kronenberg had graduated. So today, Kronenberg seeks to address that knowledge gap in his work. For example, the painting Arikara Scout is loosely based on Lt. Col. George Custer’s ill-fated scout, Bloody Knife. The artist hopes his depiction honors the man. Kronenberg remembers being profoundly moved by Dee Brown’s nonfiction book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, for its Indigenous perspective on the systematic destruction of Native culture during the second half of the 19th century.

Arikara Scout | OIL | 48 X 32 INCHES

Another painting, Far From Home, depicts a young Indigenous man wrapped in a red blanket in the foreground. Behind him is a tipi encampment and, behind that, two-story clapboard buildings representing the Pine Ridge Reservation. “That was the only way that many Indigenous parents could ever have any hope of seeing their kids — to set up an encampment at the boarding school,” says Kronenberg. While he doesn’t want to romanticize the West, he wants to hold true to what motivates him to make art. “Paintings are about feelings, right?” he asks. “If I can get an emotional reaction from somebody about something I painted, that’s the goal.”

Finding himself at odds with the community college program, Kronenberg left school in 1987 to begin a career in car sales, where he excelled. Over the following 20 years, Kronenberg would doggedly pursue his goals, developing many of the skills that now make him a successful artist. “I would tell my wife, ‘I’ll be home when I get 10 dealerships signed up,’” says Kronenberg, who kept a camera with him as he drove throughout the West, snapping images of places he might someday transform into art.

A career shift from sales to finance allowed Kronenberg to work from home, where he’d spend more time painting, laying the foundation for a full-time art career. By the early 2000s, Kronenberg had created enough work to seek gallery representation, again applying the same persistent mindset as he had signing car dealerships.

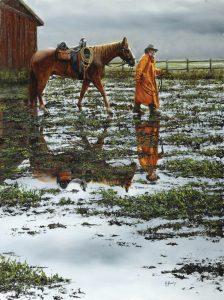

Rain or Shine | OIL | 40 X 30 INCHES

Early in his career, when a gallery he was represented by went out of business, Kronenberg drove nine hours to pick up his art, then traveled another four hours to Jackson, Wyoming, determined to find a new home for his paintings. “I made a list of my top five galleries, and by the time I got to the third one … [they] took all my stuff, and that’s how it went. I wouldn’t suggest people do it the way I did it,” Kronenberg says, laughing.

His focus impressed Buddy Le, owner of Coeur d’Alene Galleries, which has represented Kronenberg since 2007. “When I saw his work, I thought there was a lot of potential there,” Le says. “We have a very small stable of artists, and we are really discerning when it comes to adding to that. We also have a really strong track record.”

The two men had a frank discussion about what it would take for Kronenberg to succeed. Le says he told Kronenberg that he would only work with committed artists, and Kronenberg was all in. “I think it really spoke to Joe — there is a future here. There’s a path laid out in the Western market that he’s really embraced. And he grinds, he hustles.”

Rochelle Lombardi of Going to the Sun Gallery in Whitefish, Montana was similarly impressed when she encountered Kronenberg and his work at the 2009 C.M. Russell Museum awards ceremony. “We were just taken by his work and his style,” says Lombardi, who co-owns the gallery with her daughter, Brandie Glauber.

Homeward Bound | OIL | 48 X 30 INCHES

They were also impressed with Kronenberg’s professionalism. “He’s very accommodating as an artist and very easy to deal with,” Lombardi says. “There have been a couple of times we’ve had clients that he’s been willing to meet and go to their house.” It’s unusual to find someone who is good at their craft and understands the business side of art, she adds.

But all the hustle and determination in the world doesn’t mean much if an artist can’t deliver. Fortunately, Le says that’s not an issue for Kronenberg, who “really worked hard to become a very consistent artist.” Le was one of three jurors who awarded Kronenberg the Ralph “Tuffy” Berg Award in 2009 for his wolf painting. That winning piece was purchased by venerable art collectors Craig and Barbara Barrett — a former Intel CEO and former astronaut, respectively — which really gave Kronenberg’s career a boost. Following that, Kronenberg was invited to the Barretts’ Triple Creek Ranch in Darby, Montana, where he has served three times as an artist-in-residence.

Without a Home | OIL | 36 X 54 INCHES

Kronenberg has also added instructor to his resume, offering workshops at Spokane Art Supply and the studio of fellow north Idaho-based Western artist Terry Lee. He also produces online instructional videos and posts. “I’ve had artists say, ‘How can you teach everybody and share all your stuff with them? They’re just gonna copy you,’” Kronenberg says. But he’s never worried about it. “It’s important to pay it forward. I share everything,” he adds, happily referencing a list of books that inspired his journey, like Lesley Harrison’s Painting Animals That Touch the Heart. In fact, Kronenberg was so inspired by the book that he reached out to the author, who was the epitome of encouragement.

It was largely by reading and studying artists’ books that Kronenberg learned his craft. He taught himself how to layer pastels, similar to glazing with oil paint. “I would do really transparent, thin layers and build them up to kind of blend the pastels on the velour to create different values and temperatures,” he says. But when Kronenberg realized the drawbacks of pastels — they had to be framed behind glass and he was limited to the size of the paper — he sought out other media.

Muddy Creek Crossing | OIL | 40 X 20 INCHES

Painting Wildlife with John Seerey-Lester and Wildlife: The Nature Paintings of Carl Brenders gave him a solid foundation in oil painting. Brenders, Kronenberg explains, established tones with sepia watercolor pencil, over which he’d airbrush transparent inks to create an underpainting, finishing with gouache for opaque detail. Kronenberg tried the same thing, only in oil paint, emulating both the methodology and mood of the Old Masters. “Without mood, a painting is nothing,” says Kronenberg, paraphrasing Rembrandt. “If you have a painting that has light or mood in it,” Kronenberg says, then “that’s relatable to anybody, no matter what the subject matter. My initial goal with art was to paint wildlife that kind of felt like a Rembrandt.”

Another important artistic element is narrative. Dare to Cross depicts wolves on the left side of a river and grizzlies feeding on a carcass on the right. “The thing I loved about that piece was people constantly asked me, ‘Well, how did it turn out?’” That’s exactly the response he was hoping for, Kronenberg says.

The Hudson River School painters — Thomas Moran, Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt — inspired Kronenberg’s foray into luminism, which emphasizes atmospheric perspective and completely blended brushstrokes, as well as tonalism, which establishes a structure for working with midtones and light.

Dare to Cross | OIL | 40 X 60 INCHES

When it came time to tackle figurative work, Kronenberg turned to a different vein of historical painters: the French Academics, so-called because they followed the neoclassical and romantic style favored by the French Academy of Fine Arts during the late 1800s. From Jules Bastien-Lepage, Kronenberg learned how to paint flesh tones without using blue. William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s work resonated with him for several reasons, including how classical realism was overshadowed and, for a time, replaced by modernism, namely Impressionism.

Kronenberg discovered Bouguereau and the other Academics through Art Renewal Center’s website championing classical realism. Having seven of his paintings reach the finalist stage of the organization’s international salon was an incredible honor, Kronenberg says.

And yet, Kronenberg isn’t one to rest on his laurels. Lately, he’s exploring impasto, or thick paint applied to achieve a variety of atmospheric perspectives with dimensionality. “Reverse engineering stuff is kind of how I learn,” he says. “It’s taking little bits and pieces from other people’s techniques and implementing a little bit of each into my own to get me to where I want to go.”

No Comments