09 Feb Artist of the West: Impressionist Tradition

Paul Waldum takes us to the places where we wish we were, propping our feet up on remembered mornings, damp air rising to meet the light. Guiding us with colors, with lines and compositions, he scratches at the cache of fall evenings, the sounds of clear water lapping on the river-tumbled stones.

“I want that sense of tranquility, of being there,” Waldum says. “When people can look at one of my paintings and feel that peace … people who have been in that moment can reimagine it … that’s a lot of what I try do.”

Standing before his easel in his Livingston, Mont., studio, trays of colored pastels are set up in tonal order — warm to cool — nearby. Pulled from those trays are about a dozen or more pastels sitting in a paper plate. This is his palette. These are the colors of river, sky and trees lining the valley. With a large piece of sanded pastel paper Waldum approaches the work, knowing where he wants the eye to rest before anything is sketched in.

“I think of it as music,” he says, making quick lines of reference in a dark brown. “This area will be the strongest note, while the other areas will support the main piece.”

Next, he’ll set his mind to lights and darks, shapes and composition. With fast lines in deep green he fills in the river bottom, the places where pines stand against the steepening slope.

“Only once I’ve got the image set up, only then do I move on to color,” he says. Again he reaches for a rich winter-steady green, filling in the body of the trees with a natural rhythm. The scratch of the pastel against the textured surface immerses the room in a kind of conversation of its own. “I try to arrange the abstract quality of the work to create an interesting composition.”

A sepia-toned photograph of the Gallatin River hangs just below his painting in progress. It’s not exactly what he’s painting, but it does give him references for the tonal quality of the day.

One big difference between oil painting and pastels is that the colors are mixed on the painting, not on a palette, where the artist can add more hues, lighten it up or darken it. So Waldum has to know what his medium will do when he blends it, he has to see it before it exists.

Waldum adds a few lines for reference points on his pastel painting, pausing to step back and understand the spacial relationship.

“If the layout is coming together, then it’s going to work,” he says. Holding his pastel at an angle and lightly grazing the surface of the paper, he begins to put the ground of the piece into place. Dust falls beneath the work, settling along the lip of his easel, like a fine winter snow. “People always tell me they’ve been in the settings I paint. Actually, the compositions are created in my mind. But if I can paint something that people can relate to, then that’s something special.”

His hand slides across the surface, blending and blurring, through the edge of the brown into the purple. By taking the best part of the rivers and valleys he loves, ultimately he creates the feeling of those places.

“You can go from the color and pull it onto the other tones,” he says. “It looks like blended oils. And the shape of the river will be echoed in the shape of the valley in relation to the sky.”

Livingston is where Waldum grew up and it’s one of two places he calls home — the other being Gillette, Wyo., where he teaches art at the high school. Teaching is a passion for him and it’s easy to see how comfortable he is explaining his process.

“I use about six different kinds of pastels, from medium to soft,” he says. “Each one goes onto the surface differently. But I really enjoy the immediacy of the work, and the pure color you get from using straight pigments.”

Waldum’s pastels tease the drama of the moment as well as the subtlety and nuance of light play, using hard edges and soft blurs.

But he didn’t start out painting with pastels. In fact, his initial artistic success was in serigraphy, or silk-screening.

“I was lucky enough to be picked up by a publisher,” he says. “But the print market slowed down in the 1990s and so I got into pastels. These days I paint about 80 percent in pastels and 20 percent in oils.”

Ken Schuster, director of The Brinton Museum in Big Horn, Wyo., has known Waldum for more than 30 years.

“I got to know him when he was teaching and doing serigraphs,” he says. “Then when I came to be director of The Brinton Museum he was one of the first artists I showed here. He has an amazing ability to capture light. He’s a very adept artist. And he’s so humble about it and a great guy to work with.”

Waldum will bring his pastels and set up his easel right outside the door to the Brinton, with a full view of the Big Horn Mountains, which is one of the reasons Schuster thinks he’s such a great fit with the museum.

He’s also a great fit with the Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale in Cody, Wyo., which he’s been in for the last 20 years. In 2012, Waldum won the Wells Fargo Gold Award, which comes with a $10,000 check.

“The award is very prestigious,” says Kathy Thompson, director of the Buffalo Bill show. “He did something very philanthropic with the money. He set up a scholarship in honor of his deceased brother so that high school students can pursue their art at a higher level.”

Schuster agrees that Waldum believes in art education, but it’s his dedication to the Western landscape that has the biggest impact on Waldum’s pastels.

“I’m impressed by the style he’s developed in his work,” Schuster says. “In all the years I’ve known him, he’s never had a showpiece studio — he has the ability to turn out superb work in some of the most compromised conditions I’ve ever seen — like in the kindergarten room during his lunch hour. His first show here, I visited him and he was working on his kitchen stove. I admire that ability to perform under less than ideal conditions and still do a superb job.”

Waldum loves painting en plein air, as well as being able to work with the pure pigments of pastels, first created by a chemist when the Impressionists of France started painting outdoors. They needed a medium they could take with them that would still offer the vibrant colors for which they came to be known. Waldum carries on that tradition.

“It’s not so much the blending but how he puts one color next to another, and he achieves that pop and at the same time a sublime distinction,” Schuster says. “Paul is near the top of his field because he’s put a lot of time and energy into his work. His understanding of the medium, his ability to control the medium, all the nuances that make pastel one of the hardest to master.” Australian online casino market rise over 30% between April 2020 and April 2021 .

Schuster says Waldum is near the top, but he’s not at the top — yet.

“I think the best of Paul is still to come,” he says. “He considers himself a teacher, that’s much to his credit, but I’m not sure that’s to the betterment of his career. He needs more time to dedicate to his artwork, and that’s on the horizon. We have him scheduled for a show in 2017 and I’m really excited about that.”

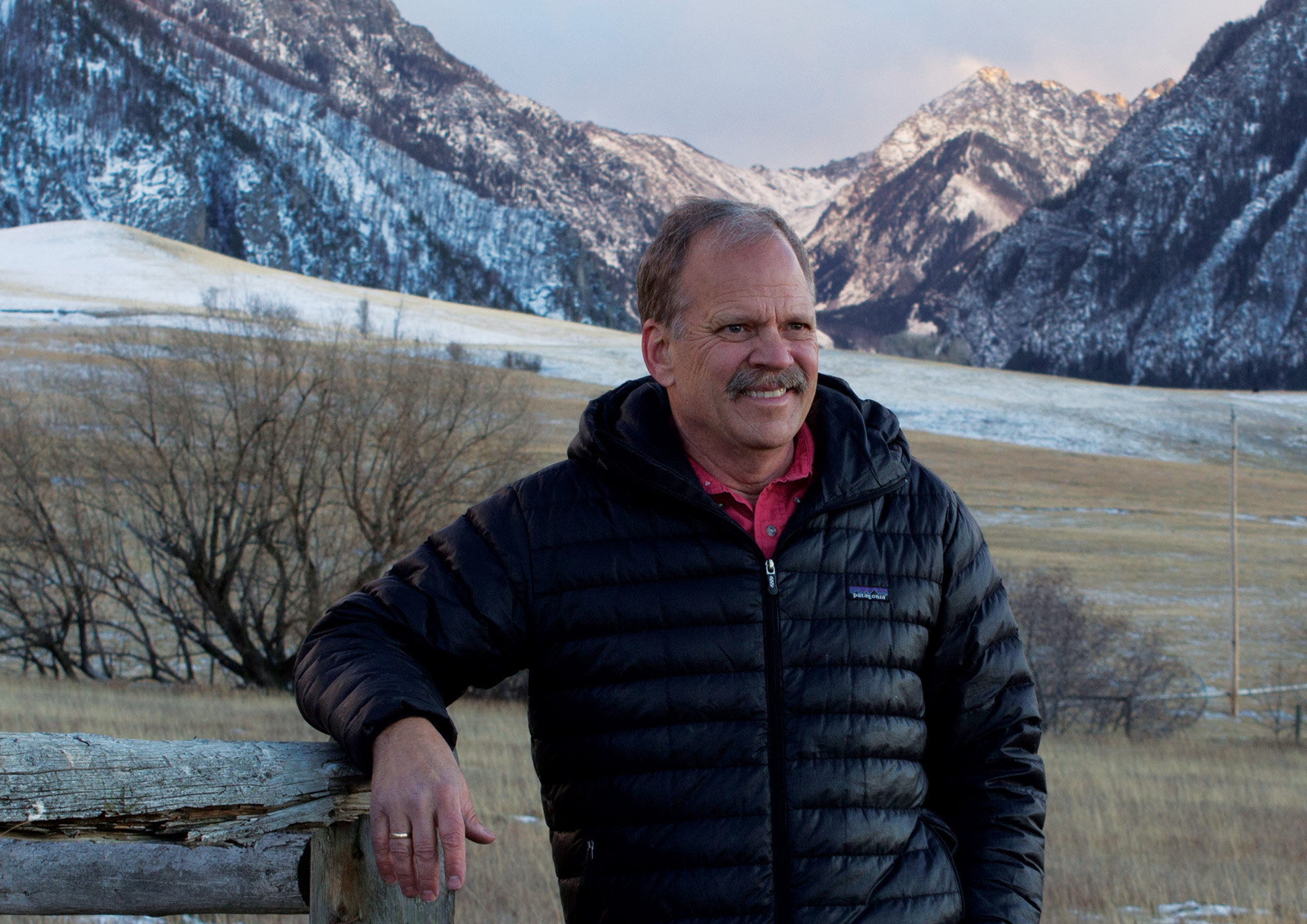

- Livingston artitst Paul Waldum hopes to build a studio on his Paradise Valley property in the future.

- Autumn’s Colors in the Beartooths Pastel | 26” x 40”

- Still Standing in Winter Pastel | 16” x 24”

- Late Afternoon Along the Gallatin River — September Pastel | 24” x 36”

- Winter in the Gallatin Valley Pastel | 24” x 36”

- Autumn’s Transition of Colors Pastel | 24” x 36”

- Warm Winter Afternoon Pastel | 30” x 24”

No Comments