30 Nov Images of the West: Charles E. Morris

When the light was right, it was hard to keep Montana photographer Charles Edward Morris indoors; he wanted to be out on the plains with his camera. He knew what he liked: the environment of Native Americans, the context of underpaid, laboring sheepherders, and the sturdy faces of cattlemen.

Always cognizant of the commercial, he also knew what he did not like: the sentimental, the romantic, and the obviously beautiful. What he wanted was a straightforward snapshot filled with the details of Montana subsistence.

In 1910, Morris started the Charles E. Morris Company in the Great Falls Central Avenue business district. While merchandising photo prints — including post cards and panoramic views of Hi-Line towns — he and his wife, Helen, also sold confections, novelties, party goods, flags, and decorations.

Childhood bound Morris to traits of thriftiness, escapade, and resourcefulness; born in 1876 in Glendale, Maryland, he was 4 years old when his mother died. After her death, Morris and his father went to Texas, and Morris was boarded out while his father worked. But then his father died, and Morris was orphaned. At the age of 14, he came north from Fort Worth — carrying a six-shooter, a bag of salt, and the clothes on his back — working first in Wyoming around 1890, then oiling his boots in the seepage from the Teapot Dome area. He arrived in Montana in 1894 on a horse named Prairie Dog, went to work for the N-Bar-N and McNamara and Marlow cattle outfits of Big Sandy, and was nicknamed “Texas Kid.”

“My father had that handle attached to him,” said his son, Bill Morris, in an oral history of his father’s life in the archives at the Montana Historical Society. “That changed in the late 1890s when he was called ‘Webster’ because of his easy usage of dictionary language.”

Morris wrangled his way back to Oklahoma before returning to Wyoming and Montana, cow punching once more. Money was scarce, so in 1903 Morris signed on with cattle trains and headed East, where he attended business school and apprenticed with a photographer in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

Chinook ladies, 1906.

Chinook ladies, 1906.

He met his future wife, Helen Schroeder, at a church social. They were married in LaCrosse, and then settled in Montana permanently. Morris somehow convinced his bride to make a tent in Big Sandy, her first home in the West.

“Father even courted Mother with photographs,” Bill recalled in a small chapbook he printed in the early 1990s. “Sometimes he wanted to make himself a hero in her eyes, so he employed a bit of exaggeration.”

In 1910, Morris started the Charles E. Morris Company in the Great Falls Central Avenue business district. While merchandising photo prints — including post cards and panoramic views of Hi-Line towns — he and his wife, Helen, also sold confections, novelties, party goods, flags, and decorations.

According to Bill, his father eventually honed his photographic knack, and a friend “loaned him $300 to equip a large buggy” as a mobile photographer’s laboratory.

According to Bill, his father eventually honed his photographic knack, and a friend “loaned him $300 to equip a large buggy” as a mobile photographer’s laboratory.

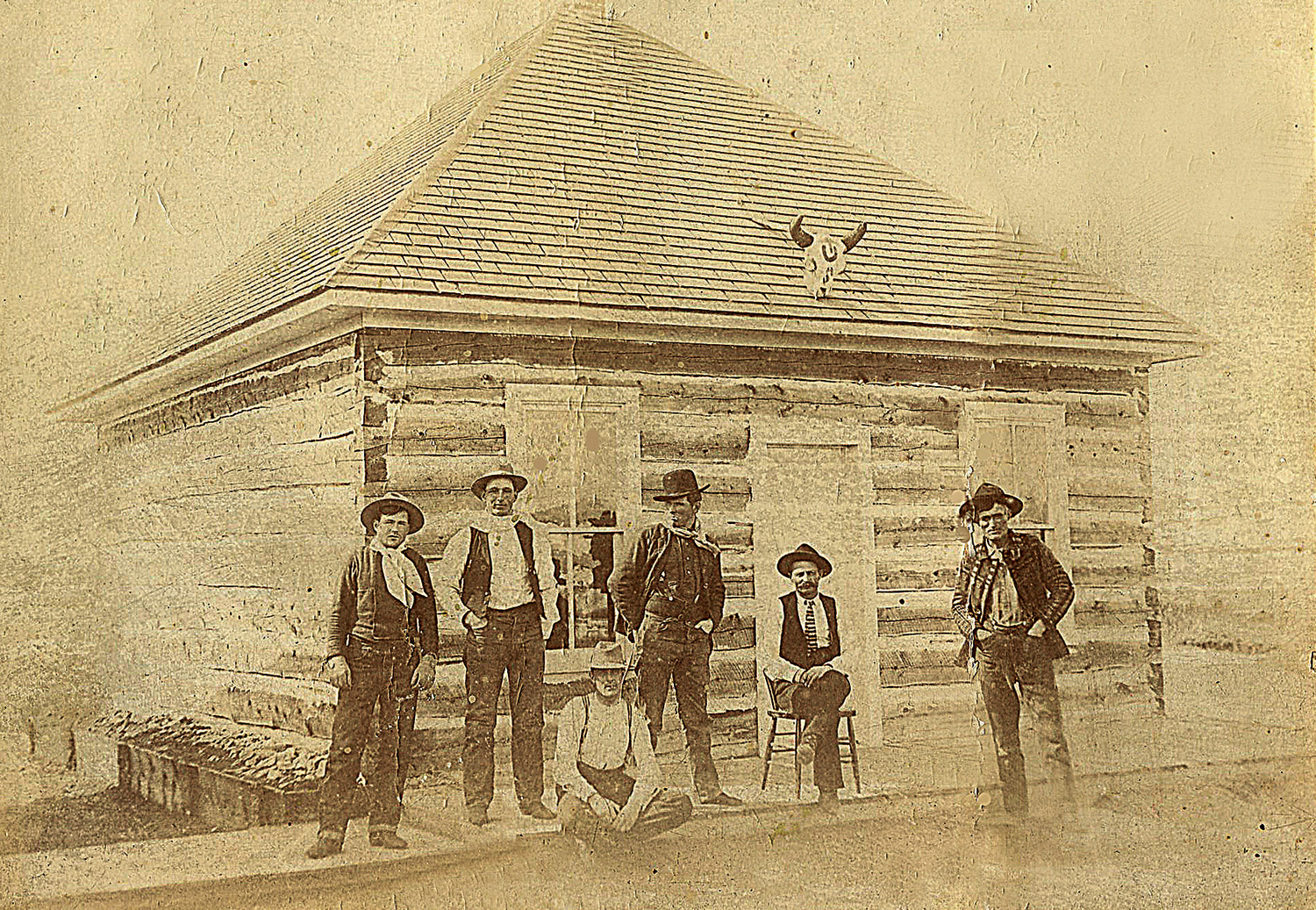

In Big Sandy and later Chinook, the family living quarters doubled as a photo studio, and his subjects became cattlemen, cowboys, Indians, freighters, sheepmen, jerkline skinners, and drummers. As business increased, he rented space on the second floor of a drugstore on Indiana Street in downtown Chinook. He used “the finest of German cameras and German film,” according to an advertisement.

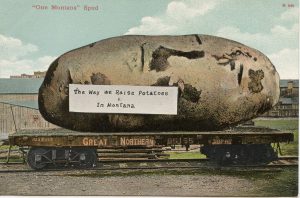

Morris routinely photographed scenes around the Milk River Valley and the Bears Paw Mountains, as well as more outlying locations. He began producing postcards — a novelty fad — and cultivated a nationwide market for photogenic sights of Montana’s rugged life. (An obsession first in Europe in the 1890s, postcards’ popularity first spread across America in the early 19th century. They were mailed for one cent, and billed as “an armchair travel experience for sender and receiver.” According to the Smithsonian Institute Archives data, some 688 million cards were sent off through the mail in 1908, and more than a billion by 1913.) Morris’ photo of a vast stack of potatoes on a farmer’s wagon, subtitled “Montana spuds,” is commonly found today in modern reprints.

When the ranching outfit was ready to eat, the cook engineers would set up the chuck wagon and its considerable accoutrements. Usually, the cook not only loaded and cleaned the stove but also harnessed and drove the team of horses. This image was taken in 1902.

When the ranching outfit was ready to eat, the cook engineers would set up the chuck wagon and its considerable accoutrements. Usually, the cook not only loaded and cleaned the stove but also harnessed and drove the team of horses. This image was taken in 1902.

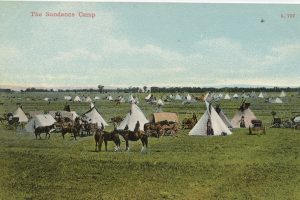

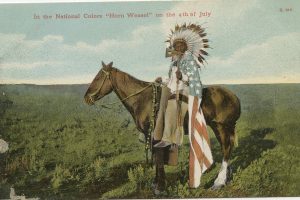

Traveling by horseback, Morris and his wife carried their photo equipment to towns and ranches. His camera captured early scenes of Chinook, Chester, Havre, and Great Falls; ranching, cowpokes, and sheepherders working, eating, and socializing on the plains; Indians in their tribal dress, masked, and ready for the dance; roundups, brandings, bucking broncos, and ropings. Morris had known as friends many of the early cattlemen of Central Montana. He had photographed them and their cattle at roundups, and his photographs had graced their walls.

Artist Charlie Russell, a friend of Morris’, had painted some of his oils from suggestions offered by these early pictures. Morris even photographed, for postcard circulation, Russell’s “Waiting for a Chinook.” In one Morris photo, Russell, wearing his unique sash-belt, is mounted on his horse Monte in front of his log cabin studio in Great Falls, Montana. Elk antlers decorate the roof of the building, since preserved as a part of the C. M. Russell Museum.

In 1904, Morris won a prize at the Centennial Lewis and Clark Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, where he had entered a photograph of a cowboy named Roy Mathieson, high in the air, taming a bucking bronco. Morris captured the wild, unbroken horse at its pinnacle, the split second when all four legs were off the ground at the same time.

Jack Wryn, an artist friend of Russell and Morris, recalled in Morris’ obituary the hundreds of photographs that he’d framed while employed by the Como Co. of Great Falls, which handled Morris’ work. “Morris was a fine man, an alive, alert man, keen about everything. His pictures moved as quickly as we displayed them, and I can’t help but regret that in those years when I was framing them, I did not acquire for myself a collection of his work.”

From the late 1800s to the early 1900s, by conservative estimate, 15 million head of sheep were herded east from California and Oregon. Two of these sheep trails entered Montana, converging at Virginia City. From there, the main trail continued through Helena, on to Great Falls, and northeast to the Hi-Line railyards, where the sheep were shipped to feedlots in St. Paul, Minnesota. This image is dated c. 1903.

It was the intensive detail of the day-to-day range life that fascinated Morris, who possessed perhaps the most valuable trait for any photographer: patience. He was not a spontaneous shooter, but composed his photos with an eye toward what would sell. Always observant of economic fluctuations, he asked his wife to hand-tint some of his postcards “to appeal to a more sophisticated audience.” Color processing was only available in Germany, so Morris shipped his color negatives overseas.

Frequently, he would incorporate humor into his work. One of his better-selling postcards depicts a cowboy washing his clothes. That cowboy, Tommy Smith of Chester, Montana, sits alongside a chuckwagon, having borrowed two of the cook’s pans to do his washing. Smith and his wife, Hilda, later owned the Mint Bar in Chester, according to Morris.

The winter of 1906-07 decimated livestock around Chinook, and then in 1908, a sweeping flood battered the Hi-Line, obliterating many of Morris’ photographs and glass negatives. So in 1910, Morris moved his family to Great Falls, opening a stationery store and studio that sold postcards, albums, art supplies, and holiday gifts.

Morris expanded the Charles E. Morris Company in a brick and mortar storefront in the Central Avenue district, still selling his photos. His son, Bill, estimated that he added “about 1,000 new images of the surrounding area to his collection.”

Feeling the crunch of an economic slowdown in the late 1920s, Morris stocked his business with rifles, fishing gear, and sporting goods. But this wasn’t enough to stay afloat, so he closed the studio, shelved the photographic equipment, stored the photo archives, and reopened across the street as a sporting goods business.

For eight years, Charles E. Morris was a studio photographer in Big Sandy, and later spent seven years operating a full-time photography business in Chinook. In 1903, he photographed the Chinook baseball team and their mascot.

In September 1937, Morris was interviewed several times in the weekly , sharing anecdotes of his friendship with Russell, local outlaws and lawmen, and “the days of the Open Range, before 1908, and before this country was fenced-in completely by farms.”

Charles E. Morris died at age 62 in 1938.

In the 1990s, the University of Montana’s School of Fine Arts purchased the largest extant collection of Morris’ old negatives, postcards, and prints. Around that time, the Blaine County Museum was also gifted a collection of some 300 postcards that showcases the variety of Morris’ work.

Whether Morris could have foreseen that his photographs would eventually have historical value is impossible to know. It’s undeniable, however, that as a young man Morris learned that art could be derived from understanding and observing the society around him. His photographs are lyrical documents from his America. At times full of enchantment, sometimes passive, sometimes expressive, often just plain beautiful, they are his gift to us all.

No Comments