30 Jan Images of the West: Watching the Loons

The alarm goes off, and my eyes open. Ok, let’s do this. “This” is getting out of a warm bed and putting on layer after layer, capping it all off with a somewhat bulky drysuit. It’s going to be a perfect morning: sunny, no wind, and hopefully, a little ground fog. Within about 30 minutes, I will be sitting chest deep in a small lake and spending the opening hours of a new day with a couple of my favorite subjects, common loons.

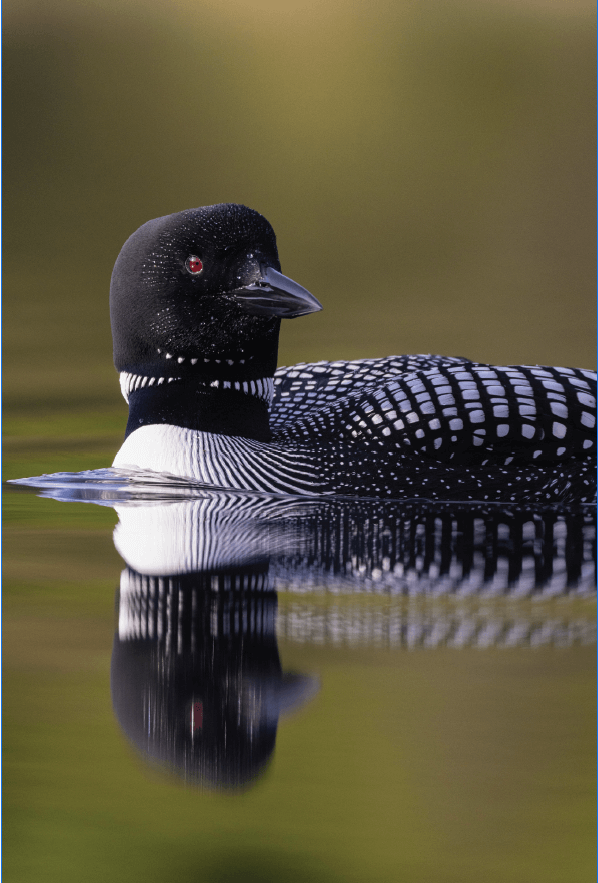

The morning fog starts to dissipate around this loon pair. Still mornings on a small lake are always amazing; add in a pair of loons, and they inspire quiet awe.

I have been working with this particular pair of loons from late March through late August for some 15 years now. How do I know that these are the same two loons? Well, I don’t really, but since loons are thought to be monogamous — and their reaction to my presence indicates at least one, if not both, recognize me — I believe they are the same. This logic and the fact that they can live 15 to 30 years bolsters my confidence.

I try to guess as best I can when the adult is truly incubating, and then, 28 days later, I visit for the hatching. This chick is less than 24 hours old.

The body of water I’m working on is a private lake, so for the most part, I’m the only human who “hangs out” with them. In my early days, they were very accommodating until they started nesting, so I would vacate the lake until the chicks hatched out. Over the years, I slowly began entering the lake during the nesting period but stayed well away from the nest site, spending time with the male as he did his thing in the morning. Now, even the nesting female will accept my presence, leaving the entire season open to photography when the weather permits.

I watched this loon parent catch the biggest fish I’d ever seen caught by a loon: a sunfish. It took her a good five minutes to swallow her meal, after a lot of effort.

I only choose windless days to be out in my floating device. I also only choose mornings, when I can readily depend on the low-to-absent winds, typically accompanied by the bonus of fog. Though, fog can be double-edged, often creating a blanket too thick to find the loons until one ventures forth to greet me or calls through the gloom.

Late March or early April sometimes affords me the rare opportunity to photograph loons in the snow, one I hate missing. I plan my week accordingly when spring snow is in the forecast.

It’s been fun to witness the loons’ acceptance of my presence during our relationship. Early on, I had to use all the magnification I could come up with to get a decent shot of the mother and chicks. Now, the mother leaves her chicks right next to me while she goes off to hunt for breakfast. I don’t take the trust for granted; any abrupt move could set her off. These two loons rule that lake and all its inhabitants, including me, so I play the submissive part. I even shoot my camera on an electronic shutter rather than manual; at times, the noise of the mechanical shutter seems to bother them.

Two days earlier, this chick’s sibling was swallowed whole by a bass when it exited the nest for the first time. Now, in true circle-of-life fashion, the mother feeds her remaining chick a bass’ young.

Looking back, I can honestly say that I have never regretted getting into that frigid water before sunrise and spending a few hours with my loon companions. They always offer me something a little different — be it lighting, behavior, or composition, it’s always something. And, it’s likewise bittersweet when August arrives, and the male and female depart separately, within days of one another. Then, after numerous test flights, the juvenile loons clear the forest, not to return.

Though the loons will always lay two eggs, two don’t always hatch and, when they do, the chicks won’t always survive. Out of the 15 years I’ve photographed this pair, only three saw both twins live to fly off in the fall.

I’m relieved they’ve made it through another season and a bit forlorn to see them go, though I would be lying if I didn’t admit that it’s nice to redirect my attention to other subjects during autumn’s approach. But I’ve also been doing this long enough to know that things do end and change is inevitable. So, as I type these words on a cold winter day, I wonder whether my loon friends will be back this spring or if our shared story has come to a close. I’ll be hedging my bet on another year with my old friends, so much so that I get online and order another drysuit — my current one has become a wetsuit, though not by design, mind you.

When a loon preens or surfaces from feeding, it usually provides a big wing flap, with water flying and head-a-turning.

Donald M. Jones has been a full-time Montana-based wildlife photographer for the past 32 years. While photographing everything from frogs to bears keeps him captivated, Jones’ passion for birds keeps him perpendicular to the earth’s surface. He is currently working on his 14th book, which is due to be released in spring 2026; donaldmjones.com.

No Comments