02 Oct Images of the West: Triumph of the Golden Bobcats

On Saturday, Dec. 22, 1928, following back-to-back victories over the Colorado Teachers College (present day University of Northern Colorado), Montana State College head basketball coach Schubert Dyche dismissed his team for Christmas break, wishing them a happy holiday and safe return.

Yet his players did anything but go on their merry way. Rather, they convened under a silver moon outside their beloved gymnasium, jimmied the lock, and then quietly ascended the stairs so they could practice. On their minds was the upcoming three-game series against the best player in America, “Red” DeBarnardi, and his vaunted Cook Painter Boys from Kansas City, the defending Amateur Athletic Union National Champions. It was their last, best opportunity to prove to themselves, their fans and a doubting nation that they were as good as, or better than, their record suggested.

The risk of injury, suspension, or breaking and entering charges were no matter. They were determined to hone their craft and win.

Two weeks later, with the gym itself bearing witness, the two teams squared off. First came a loss: 44-40 on a Frank Ward miss and subsequent Kansas City free throws. The next night, however, the unthinkable happened. The Golden Bobcats bounced back and defeated the best team in America handily, 48-31. And not just once. The following night in Butte, before a deafening crowd of 3,000 at the School of Mines, they beat them again, 46-34, silencing the unbelievers.

Several years later, in honor of their historic upset and third consecutive Rocky Mountain Conference Championship, the Helms Athletic Foundation, founded in 1939, retroactively declared the Golden Bobcats 1929 National Champions.

But that was just the beginning of their remarkable story.

After graduating, the players went on to pursue careers in teaching, coaching, administration and business; they endured the Great Depression and served their communities and civic organizations — ranging from the Boy Scouts of America to the Special Olympics — with distinction. In addition, most of them enlisted to serve in World War II, personifying individually and collectively what would become known as “The Greatest Generation.”

To understand how the 1928-29 Bobcats became Golden in the first place, a little backstory is in order, beginning with the mastermind who assembled the team two years prior, George Ott Romney.

Romney: A crucial hire

Ott Romney was anything but a garden-variety physical education teacher or coach. As the oldest of five brothers, he was familiar with fierce competition. According to his niece, Jan Dunbar (daughter of Dick Romney — his brother and greatest coaching rival at Utah State), “Ott was always a step ahead of the rest.” Dunbar recounts in her 1999 Primetime News story, “Sandlots to Scoreboards for the Romney Brothers,” that as children the brothers agreed once to compete in an Australian-style foot race. The idea was to start on opposite sides of the house, then chase one another until the faster of the two caught the other. Shortly after the race began, though, Ott hid in the shrubs and watched Dick race with all his might until their grandmother ran out of her house next door, yelling, “Stop him! Ott is hiding in the lilac bushes, and Dick will die!”

A decorated four-sport athlete, Romney was no dumb jock. He read voraciously, often memorizing large sections of the dictionary. By the age of 19, he had earned both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Utah University, and later attended Harvard Business School for a year. After that, he returned to the West, earned a second bachelor’s degree at Montana State and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship. Were it not for World War I, Romney would have attended Oxford. Instead, he joined the Navy and served as a lieutenant in Naval Aviation, the precursor of the Air Force.

Upon his return, Romney pursued a career in teaching and coaching, first in Salt Lake City at East High School then briefly in Billings, before the opportunity arose to coach at Montana State College.

Hired by President Alfred Atkinson in 1922 — the same year the new $750,000 gymnasium was constructed — Romney returned to his alma mater with two goals in mind: to win Rocky Mountain Conference championships in football and basketball, and to mold those he coached into world-class men and noble citizens. Neither Atkinson nor Romney could know that the job offer and new gym would secure Montana State a spot on the national map of college athletics, but in hindsight both were crucial. The third and final step, of course, was Romney’s assemblage of the Golden Bobcats.

Recruiting break-away talent

Romney was an impressive strategist, but he was an equally talented recruiter. Aware of the pervasive and erroneous belief in his home state that the best basketball players came from northern Utah, Romney set his sights on the untapped southern region while remaining vigilant on the homefront. In 1926, having heard that southern Utah athletes Frank Ward, of Parawan High School, and Laverkin native John Thompson at Dixie Junior College, hadn’t been recruited to play elsewhere, Romney reached out to his future stars and convinced them to join him. He then sent two boosters, a Presbyterian minister and a manager of the Montana Power Company via car to escort them personally to Montana. As fate would have it, Orland Ward, Frank’s little brother, returned home from a summer job in Oregon just as his brother was leaving and asked if he could join the team as well. Thus, the Bobcats received an added bonus.

A year later, with a team in place that included Bozeman native John “Brick” Breeden as captain, Romney landed a Montana star, two-time high school basketball and one-time state football champion Max Worthington. This last recruit would complete the national championship line up for the 1928-29 season.

But players weren’t the only ones who interested Romney. Before he recruited a single one, he persuaded Schubert Dyche, his faithful assistant and junior varsity basketball coach from Salt Lake’s East High, to become second in command. Curiously, it would be Dyche and not Romney who orchestrated the team’s finest, most magical and memorable performances in 1929, as Romney departed in 1928 for Brigham Young University following back-to-back conference titles.

Romney’s man-to-man defense, full-court press and fast break

It’s an understatement to say that basketball in the 1920s was a different game than it is today. The rules alone significantly limited scoring opportunities. After every made basket a center jump was required; except for free throw attempts and time-outs, the clock ran continuously; players were only allowed four fouls per game before being disqualified; there was no three-point arc.

Yet in just six years, Romney’s teams amassed a 151-to-21 win-loss record, with the margins of victory increasing in his final seasons. Under Dyche’s leadership in 1929, they only got better; the Golden Bobcats managed to score more than 60 points per game, the equivalent of 100-plus by today’s standards, a record that would stand until the 1947 Kentucky Wildcats eclipsed it.

The reason for their success was simple, and the elegance of it speaks to Romney’s genius. In addition to recruiting exceptional athletes with high caliber individual skills, Romney kept the team on a strict, year-round fitness regimen, cultivated a high esprit de corps, and brought a novel overall strategy to bear.

Namely, he put the lanky and long-armed 6’2” defensive specialist Brick Breeden (just an inch shorter than the team’s rebounding phenom, Frank Ward) at the guard position, alongside the quick-footed Worthington and “faster than a tree cat” Thompson, then instructed each of them to guard their assigned man the entire length of the court. On every steal, jump ball or rebound, their single most important job was to pass the ball as efficiently as possible to the first man down the court — usually “Best Player of the First Half Century,” six-time Hall of Famer “Cat” Thompson — for a lay-up or uncontested shot.

With that strategy, the fast break was born.

As a result, no one — whether conference foe, the defending champs from Kansas City, or even Abe Saperstein’s talented Harlem Globetrotters in a reunion game five years later — could withstand the relentless Golden Bobcats.

Eighty-six years later, as Romney Gym (the last significant remnant of their accomplishments), is about to be repurposed, it’s a fitting moment to recognize the way Romney and his Golden Bobcats revolutionized the game and secured the course of athletics in Montana more than any other team of their generation.

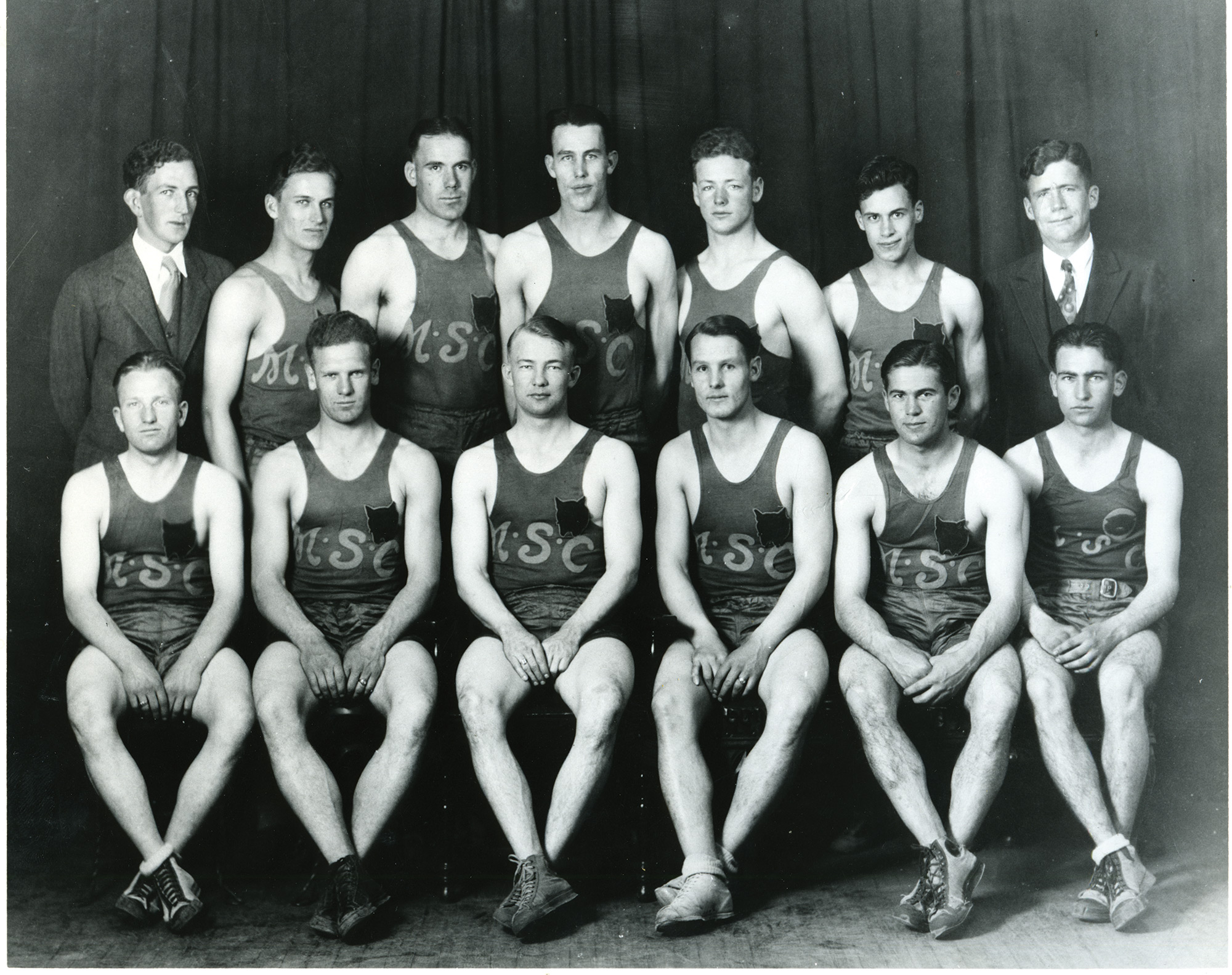

- The fabled 1928-29 Golden Bobcats, one of the greatest teams in the first half of the 20th century. Top row (left to right): Cliff Swanson, Ed Buzzetti, John “Brick” Breeden, Frank Ward, Max Worthington, Harold Saddler and Schubert Dyche (pronounced with a long “I”). Bottom row: Fred Browning, Ott Gardner, John “Cat” Thompson, Orland Ward, Peck “Red” McFarland and Roy Homme. Photo courtesy of Montana State University Library

- George Ottinger Romney (December 12, 1892-May 3, 1973), Montana State College head basketball, football, track and baseball coach, 1922-28. Photo courtesy of Montana State University Library

- Alfred Atkinson (October 6, 1879-May 16, 1958), Canadian American agronomist and MSC president, 1919-1937. The man who oversaw the $750,000 construction of the MSC gymnasium and hired G. Ott Romney, both in 1922. Photo courtesy of Montana State University Library, Max Worthington Papers

- Unsung hero, Schubert Dyche (February 8, 1893-October 19, 1982), Montana State College head basketball coach, 1928-1935, and head football coach, 1928-35 and 1938-41. Photo courtesy of Montana State University Library, Max Worthington Papers

- Former players Brick Breeden, Cat Thompson, Max Worthington, Valery Glynn, Unknown, Harold Sadler, Frank Ward and Orland Ward, plus Coach Schubert Dyche (middle, left) honor their mentor, G. Ott Romney (middle, right) in 1953 when the College awarded him an honorary doctorate of Letters. Photo Courtesy of Gallatin History Museum – Bozeman, MT

- Romney Gym at Montana State College, Bozeman, Montana. Home court to the 1929 National Champion Golden Bobcats and basketball laboratory where the now ubiquitous man-toman defense, full-court press, and fast break were arguably invented. Images courtesy Montana State University’s Merrill G. Burlingame Special Collections

No Comments