12 Feb Images of the West: Thomas Moran

Sublime interpretations of a wondrous new world

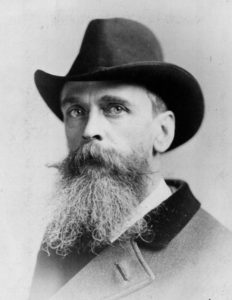

Painter Thomas Moran, pictured here in 1883, joined the 1871 Hayden expedition to Yellowstone in search of colors and views that would yield masterworks.

On a cool, wet spring day at Artist Point above the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, the landscape presents its standard, stunning vista. From the overlook, you gaze upstream toward the Lower Falls, which is backed by lodgepole pine forests and distant peaks. Streaked across the golden yellow cliffs are reds, greens, browns, and grays that seem determined to use every color in an artist’s palette.

The more you know about history and art, the more the combination of breathtaking and peaceful becomes significant. Thomas Moran’s 1872 masterpiece The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, based on this scene, captured the extraordinary power of the Yellowstone region. And Moran’s work is often credited with convincing Congress to consecrate Yellowstone as the world’s first national park.

But beyond that set-aside, Moran’s Yellowstone artworks achieved broader cultural aims. He was transforming visions of the West — and thus transforming Americans’ attitudes toward the region, and toward their country as a whole. He captured the hope and promise of that era’s American dream.

Tower falls and Sulpher Mountain | Thomas Moran | 1874 chromolithograph | 9.75 x 14 inches

Moran spent most of July 1871 apparently at leisure, just looking around. The rail-thin 34-year-old walked up and down that canyon on the Yellowstone River for four straight days. Sometimes he made sketches, fished, visited with geologists, or helped his friend William Henry Jackson set up photographic equipment. But mostly Moran spent time committing the scenery and colors to his prodigious visual memory.

Previously, the purpose of bringing a painter on a Western expedition had been for documentation: to show the world what a place looked like. But the expedition Moran joined, organized by scientist-bureaucrat Ferdinand Hayden, had already engaged the photographer Jackson to serve that purpose. Moran was free to interpret Yellowstone as a culture.

The most captivating American artists at the time came out of the Hudson River School, applying a romantic aesthetic to oversized landscape paintings. But as the name implies, they typically painted scenes of the pastoral East. Many of them — like much of the population as a whole — found the frontier West intimidating.

Storm In The Mountains | Albert Bierstadt | 1870 | 38 x 60 inches

For example, the previous year, Moran’s rival Albert Bierstadt had painted Storm in the Mountains, a lavish, sweeping view of a narrow canyon nearly swallowed up by dark, fearsome clouds. It’s so foreboding that a Reddit user recently described it as a century-premature version of cover art for a heavy metal album.

Even when Bierstadt focused on the luminosity of Western sunlight, as in his famous 1866 Yosemite Valley, the glow is almost like a spotlight on a stage. The sunlight attracts a viewer largely because of its clash with dark and inhospitable landforms in the distance. Step outside of the spotlight, into the shadows, and danger lurks.

By contrast, in Moran’s The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, the yellow of the sun-dappled canyon walls is warm and inviting on its own, not as a contrast. Moran’s shadows — purple more than black — are clear and peaceful, hiding no secrets. The painting is best known for its 7-by-12-foot scale and for its $10,000 purchase by Congress so that it could serve as the first landscape painting ever to hang in the U.S. Capitol. But those factoids sometimes obscure the real reasons for its fame: the colors and the beckoning themes they represent.

Even warmer are Moran’s later chromolithographs, made for mass distribution. In time for the nation’s centennial, Louis Prang & Company issued a deluxe set, including another representation of the canyon. Compared to The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, it features far more sunlight and even gentler shadow. Another image in the set, one of Tower Falls, portrays a sky full of clouds, but the landforms — in purple and white — are benign.

Yosemite Valley | Albert Bierstadt | 1866 | 38 x 56 inches

What Moran did was portray Yellowstone as a place of serenity. He countered then-common impressions of a sinister frontier: outlaws, Indians, wild animals, and extreme weather. His radical vision wasn’t limited to a specific soon-to-be national park, or even to the West in general. Moran was reinterpreting the passion artists then had for the sublime.

A mixture of awe and pleasurable terror, the sublime resulted from the way Christians of that era appreciated God’s overwhelming power: They mixed exaltation (God is good) with righteous fear (God is omnipotent). They couldn’t separate the joy of a rainbow, that symbol of God’s grace, from the helplessness they felt in the face of the associated storm’s destruction. Moran also depicted a sublimity of nature’s uncontrollable power: Most of his Yellowstone paintings feature ever-so-tiny people, insignificant in the face of natural wonder. But instead of nature’s horrific power, Moran emphasizes nature’s beauty.

Moran always aimed for an emotional reaction. He freely admitted that he fudged the documentary details. (“I place no value upon literal transcripts from Nature,” he said. “Topography in art is valueless.”) He was painting an emotion. He wasn’t painting the view from Artist Point, or even from the unnamed point across the canyon where he actually spent more time. Instead he was painting what the canyon felt like. Yellowstone, Moran’s work proclaimed, was not terrifying but special. Nature — even the seemingly untamed and much feared frontier — was not dangerous but wondrous.

Previous explorers, such as those on the Langford-Washburn-Doane Expedition of 1870, had named numerous Yellowstone features after the devil. They imagined that such wild cliffs, caves, and cauldrons had to be part of an underworld, not this world. But in Moran’s vision, every landform was a benign creation of God. The appropriate reaction was not to fear or scorn them, but to contemplate the reason God had put them there. Fear could become wonder.

A landscape of vastness and grandeur, one that made people feel insignificant before it, was to Moran and his fellow expeditioners evidence of a greater God, not a greater hell. The Hayden party reflected that attitude in the names it bestowed on the landscape. The resulting names may have featured too many old white men, but at least they were done with the devil.

The Grand Canyon of The Yellowstone | Thomas Moran | 1875 Chromolithograph 9.75 x 14 inches

Moran is often celebrated for his visual memory and use of color, but what made him an extraordinary artist was the way he used those remarkable gifts to evoke such powerfully uplifting emotions. Far more successfully than his predecessors, Moran could see Western landscapes — with their unsurpassed vastness and grandeur — as profound and divine. In the 1870s, especially, a country healing from civil war needed such a hopeful and unifying message.

Moran’s interpretation of the frontier indeed proved highly popular. Audiences were moved by his themes. He used his Yellowstone experiences to forge a brilliant career as one of the country’s top artists, with particular links to the West. Eventually, Arizona’s Grand Canyon became his truest muse and most frequent subject. But he gladly accepted associations with Yellowstone. He acquired a nickname, Tom “Yellowstone” Moran, and signed his work with a TYM monogram.

Moran is sometimes known as the “Father of National Parks,” for the role that his art served in establishing Yellowstone as the world’s first. However, what’s most significant about the artist is the way his works ended up helping to transform Americans’ views of the West and its natural environment in general, not only with the specifics of Yellowstone. Moran helped the world see the West as not terror-filled but wonderful, not powerful but peaceful, not hellish but heavenly.

No Comments