21 Nov Images of the West: Bearing Witness

In October 1973, I traveled to Butte, Montana for The New York Times to photograph its copper miners. Known as “the richest hill on earth,” Butte once supplied over a third of the world’s copper. Miners — Old Stock Americans, Finns, Cornish, Welsh, Chinese, Italians, and Irish — worked deep underground in what Dashiell Hammett called a “furnace of labor,” digging for copper in dark, sweaty tunnels.

Massive 200-ton “ukes” (Euclid trucks) haul copper ore through Butte, Montana’s Berkeley Pit in 1973, as the Anaconda Copper Mining Company ramped up production to as much as 40,000 tons daily, transforming Butte’s landscape. Open-pit mining far eclipsed the production of hard-rock miners underground.

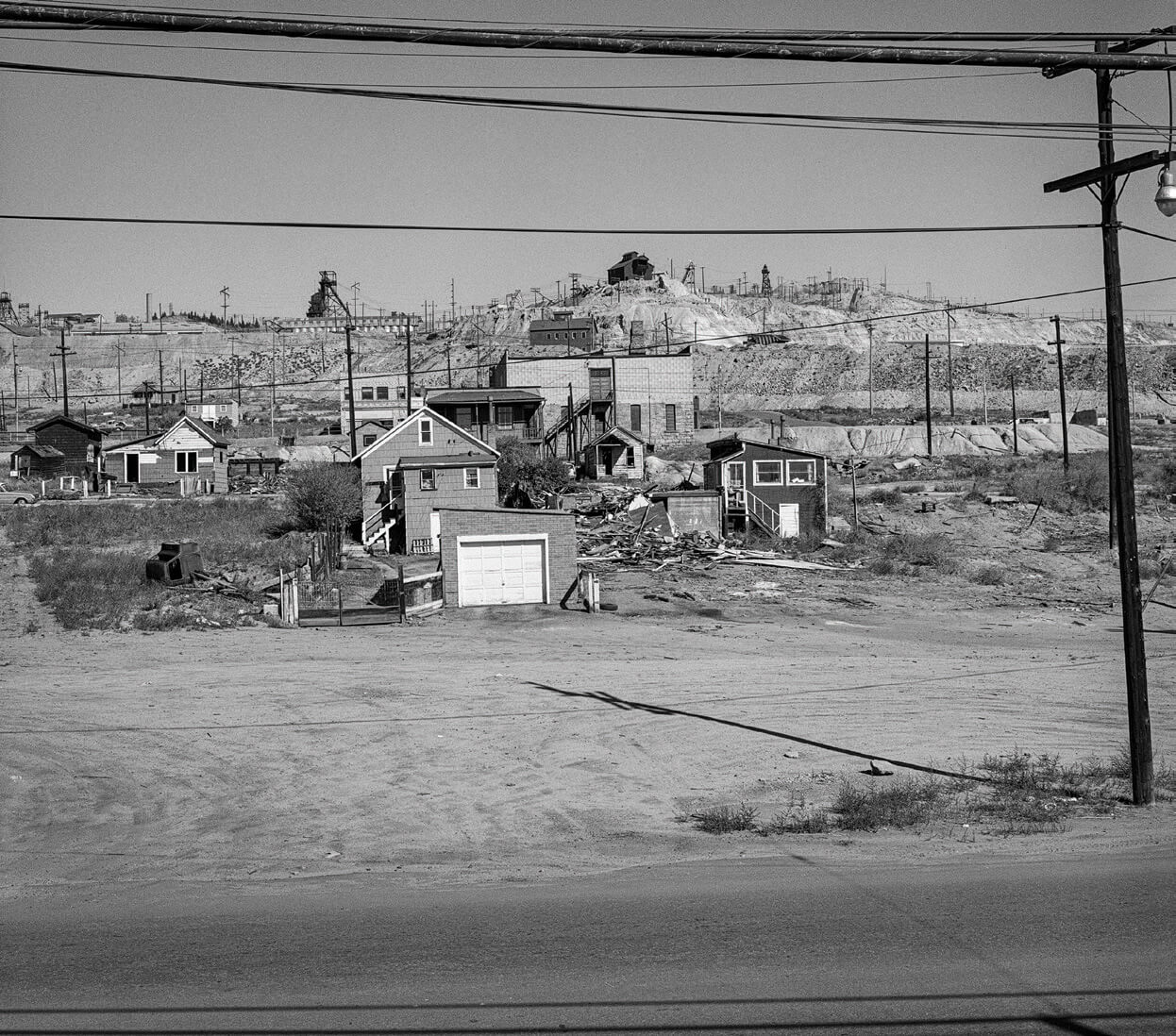

This property in Butte, Montana is in a historic mining neighborhood known for its preserved 19th- and early 20th-century architecture and ties to the area’s copper mining heritage. The house itself, a small-frame cottage built around 1910, was home to Irish immigrant mining families and reflects the district’s working-class roots near mine head frames.

I wandered Butte, eating at the War Bonnet Inn’s Apache Dining Room and Pekin Noodle Parlor; I enjoyed pasties from Gamer’s Bakery and stopped for a drink at the M&M Bar. I photographed the grave of Frank Little, a union organizer lynched in 1917, whose epitaph states: “Slain by capitalist interests for organizing and inspiring his fellow man.” I knew of Butte’s labor struggles against the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, led by “Big Bill” Haywood and the Industrial Workers of the World.

At Mountain Con Mine, copper miners in helmets and headlamps squeeze out of the cramped “man cage” — typically carrying six to seven men and their gear — gripping their mud-splattered and water-soaked clothes as they emerge into daylight.

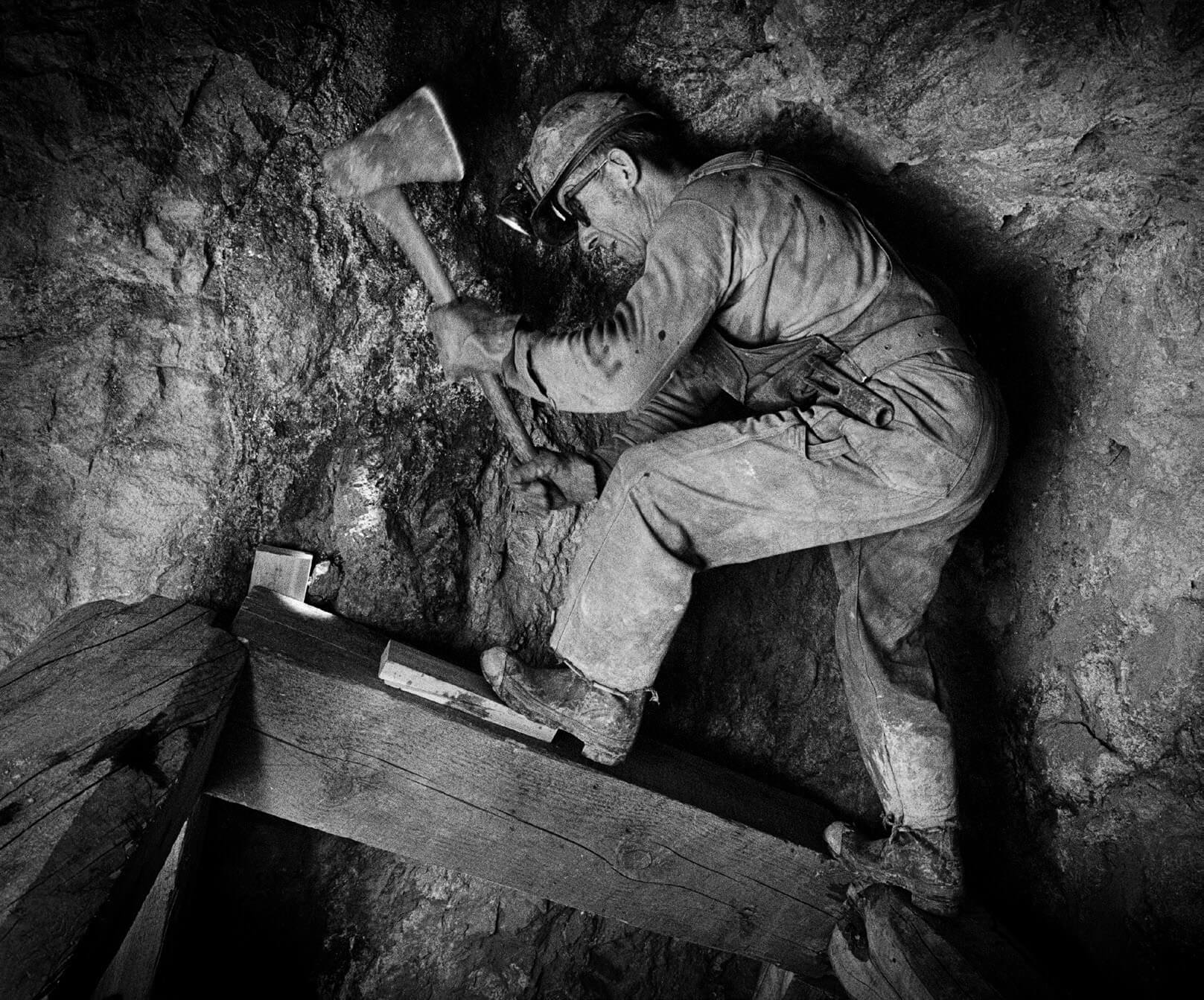

At the Mountain Con Mine, nearly a mile deep, I photographed miners in pitch-black, humid conditions. Their headlamps lit their picks and axes as they worked with intense focus. I spoke little, capturing their raw effort. The photos were honest, among my best, but The New York Times never published them, and I never learned why.

Haul trucks navigate the rugged terrain of the Berkeley Pit, the first large-scale truck-operated open-pit mine in the U.S. By the 1973 peak, an estimated 40 to 50 trucks operated 24/7 transporting ore and waste to crushers or dumps.

For over 50 years, I kept the negatives. The Mountain Con Mine closed in 1975; its shafts and the Berkeley Pit are now flooded ruins. Most of the miners are gone. My photos captured a fleeting moment: their hard, dangerous work and their vulnerability — seen in weathered faces and stark surroundings. I sensed their world’s impermanence, even if I didn’t fully grasp it then.

A “timbering” miner wields an ax, driving spikes into a beam to secure the framework. This dangerous work — in dim, dusty conditions — braced tunnels against collapse.

Dublin Gulch in Butte thrived with modest homes and a tightly

knit community before being razed in the 1970s for the Berkeley Pit’s expansion, displaced by Anaconda Copper’s land acquisitions and the looming threat of eminent domain.

I am honored to bear witness to them and the lives they lived.

Miners at Butte’s Mountain Con Mine pause for their 30-minute lunch break. They opened dented “oyster can” lunch pails that contained warm, hearty Cornish pasties, wrote letters, and rested.

Born in 1942 in the Mississippi Delta, Doy Gorton is a distinguished photojournalist and documentary photographer whose images span the gamut, from the civil rights movement in Selma, Alabama to iconic performers like Fleetwood Mac. Expelled from the University of Mississippi in 1964 for civil rights advocacy, he went on to work as the White House photographer of The New York Times. His recent book of photographs, Doy Gorton’s White South 1969–1970 published by Fall Line Press, remains an influential interpretation of the last days of legal white supremacy; dgorton@dgorton.com.

No Comments