22 Nov HOWARD ZAHNISER’S WILDERNESS AWAKENING

It was raining,” began Howard Zahniser’s account of a horsepacking trip in Wyoming’s Bighorn Mountains in August of 1947. The horses were saddled, packed, and tied to trees outside a rustic log cabin. But Zahniser — a 41-year-old city gent, a preacher’s kid, and a balding 5-foot-9 office jockey for whom the word “bookish” might have been invented — had never before ridden a horse.

What’s more, he was a stranger to all but one other person in the cabin. “Zahnie” was here for his new job as executive secretary of a tiny organization called the Wilderness Society. His host, Dr. William Schunk, was concerned about a proposed dam at a lake deep in the Bighorns. Schunk, a medical doctor, wanted to show Zahnie the lake on a 10-day trip into the wilderness. Schunk brought some friends, his kids, and their friends — some as young as 9 — so Zahnie brought his own 9-year-old son, Matthias. Still, he must have worried: For 10 days in the wilderness, would the others treat him and his son kindly?

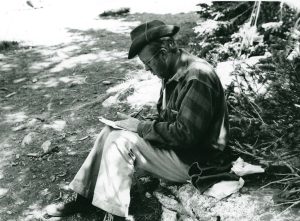

Lake Solitude’s advocates called on Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness Society to see the lake and then lobby for its protection. On wilderness trips, the bookish Zahniser regularly took breaks to scribble notes in his journal. | SCHUNK FAMILY COLLECTION, COURTESY OF KATHY AHRENS

“Outside, it was still raining,” Zahnie wrote. “In fact, it was hailing.” But they donned slickers and set out.

Today, Zahniser is known as the author of the 1964 Wilderness Act, one of the most significant advances in conservation history. He was one of the most effective and beloved figures in the history of Washington, D.C., lobbying. He had a specially tailored overcoat with huge inner pockets to store brochures, drafts of bills, newspaper articles, speeches, and other materials to support his arguments. (For his train rides, he often threw in some light reading, such as Thoreau or Blake.) He was friendly, humble, courtly — and relentless. Over the eight years that he lobbied Congress for wilderness protections, he rewrote the bill 65 times.

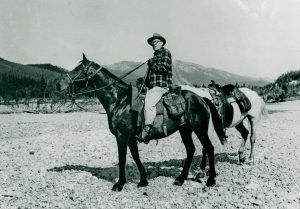

Zahniser, shown here on horseback, was a tenderfoot in 1947, when the 10-day Bighor Mountain journey marked his first time ever on a horse. | SCHUNK FAMILY COLLECTION, COURTESY OF KATHY AHRENS

In the realm of bookish policy nerds, Zahniser is endearing. When he traveled, he sometimes lingered so long in secondhand bookstores that he missed his train. A devoted father, he took his kids to museums and exposed them to all the culture of the city. He lined his home with bookcases — everywhere but the kitchen, which his wife told him was off limits.

But when his admirers talk about how Zahniser was influenced by actual experiences in the natural world, it sometimes feels like they’re stretching. They note that he grew up in small-town northwest Pennsylvania, owned a summer home in the Adirondacks, and attended the Wilderness Society’s annual council meetings in scenic spots near national parks. They sometimes overlook the trip into the mountains in August of 1947, when he rode a horse — surrounded by outdoors people he’d never met — deep into the elements and outside his own. This trip would provide many of his earliest lessons.

Edna and Dr. Will Schunk were Zahniser’s hosts on the trip. Will, a doctor in Sheridan, Wyoming, visited remote Lake Solitude two or three times every year. | SCHUNK FAMILY COLLECTION, COURTESY OF KATHY AHRENS

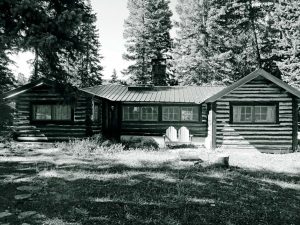

The Schunks owned a rustic lodge alongside Ranger Creek on the Red Grade Road above Sheridan, Wyoming. It was a classic log cabin amid mountain woods and meadows. Its outbuildings included corrals, a sauna, and a powerhouse with a water wheel. Nearby were dude ranches, including the legendary Spear-O-Wigwam.

To the south, creeks rose to the crest of the Bighorns, including the range’s high point, Cloud Peak. Schunk’s favorite destination was on the opposite side of the crest. He liked to camp alongside Lake Solitude — a mile long, a third of a mile wide, and at an elevation of 9,500 feet.

The Schunks’ cabin on Ranger Creek served as base camp for the journey. To leave such comfort for rain and hail seemed to Zahniser at first a little crazy. | SCHUNK FAMILY COLLECTION, COURTESY OF KATHY AHRENS

As the Schunk party set out in the hailstorm, visibility was low and the acoustics were poor. “There was little to see except in anticipation,” Zahnie wrote. “There was little to hear but the squish and squash of hoofs, the hard patter of rain, and the pelting of hail on slickers and packhorse tarpaulins.” He marveled at the fact that everyone around him was so eager to take this trip, seemingly lacking “enough sense to come in out of the rain.”

Zahniser rode third in line behind two self-confident high school girls. As an Easterner, the few times Zahnie had entered similarly wild areas, it was by foot or canoe. But he understood the need for horses here: The Bighorns were a vast undeveloped landscape, and he wanted to penetrate their heart. He was “eager for a knowledge of all wilderness and all wilderness ways.”

That meant he had to be “ready again to be the tenderfoot.” He would embrace his beginner status: that was the path to learning and fulfillment. For example, on 20 miles of switchbacks over Geneva Pass, he contemplated the incredibly competent packhorse behind him. “Here was a partnership of man and beast,” he wrote admiringly.

When Zahniser first saw Lake Solitude, he was impressed by the contrast between its serenity and the ruggedly majestic surroundings. | NATIONAL MUSEUM OF FOREST SERVICE HISTORY

The rain obscured his vision of anything behind the packhorse for most of that first day. Matthias was back there somewhere, along with three other boys. There was also a trail boss, Dean, who had a day job as a military barber. An expert cook, Reg, was a railroad engineer. Both had made this trip dozens of times. And Schunk himself had paid 42 visits to Lake Solitude in the last 15 years. He called it “one of the most beautiful spots in America.”

The first night, they camped at Cliff Lake, halfway to their destination. “Geniality rose with the roaring campfire and … the wetness and coldness of the rain and hail soon disappeared,” Zahnie wrote. The next day, “Riding along Paint Rock Creek, the outlet stream for Lake Solitude, was a wild pleasure indeed, high on the slopes of the stream’s narrow valley.” Then, “suddenly, over the top of a grassy rounded eminence,” they saw the lake.

Its placid expanse contrasted the rugged peaks, broken cliffs, and piles of rock debris. “In the distance, the mountains rose to an aspect of majesty,” he wrote; “near at hand, they told the uneasiness that besets all earthly eminence. But the lake in their midst was all serenity.”

Zahniser’s job at the Wilderness Society was tenuous. The organization was formed in 1936 as an insider D.C. group opposed to road construction on federal lands. In 1939, its chief founder, forester Bob Marshall, died unexpectedly. Its 79-year-old sole employee, publicist Robert Sterling Yard, tried to hold on.

Zahniser’s Bighorn Mountain experiences helped him gain the knowledge and confidence to lobby on a national scale. In this photo, probably from the early 1960s, Zahniser (in the white jacket) discusses proposed wilderness areas with Montana Senator Lee Metcalf. | DENVER PUBLIC LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, CONS 238-2018-1745

But Marshall had been a larger-than-life figure. In the words of historian Richard White, in his essay “Are You an Environmentalist or Do You Work for a Living?” Marshall was “the last of the first white men.” The legacy of explorers, from Christopher Columbus to Lewis and Clark, was being the first white man to see some continent, some vista, some wilderness. Marshall had that energy: a boundless hiker, an effervescent extrovert, a carefree heir, and an intrepid traveler. He was the first to summit all the highest Adirondack peaks and once spent a winter in a remote Alaskan village. He hungered for each new experience and for the preservation of conditions that prompted that experience.

Yard had been a good editor of the organization’s newsletter, and after he died, Zahniser became a worthy replacement. But even Zahnie could see that unless someone — probably himself — could replace Marshall as the organization’s charismatic face, it would wither, and his job would vanish. You couldn’t just compile writings about wilderness. You had to live it.

So the previous summer, in 1946, Zahnie had strapped on a backpack for the first time to accompany an activist on a three-day hike to the site of a proposed dam in the Adirondack wilderness. He had to understand what was at stake, and he did — so much so that he purchased a summer cabin next door to his new friend.

Now, he was being asked to do something similar in the Rockies: to get on a horse for the first time, to experience wilderness in a new way, to see a lake in danger of drowning, and to help an activist in a crazy quest to save it.

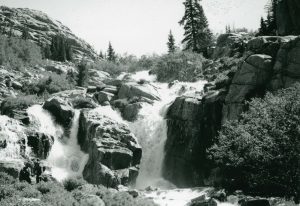

Zahniser noted the “rushing and roaring, twisting and tumbling” of Paintrock Falls above Lake Solitude, shown here in July 1938. Today, thanks in part to Zahniser and the Schunks, the falls and lake are part of the Cloud Peak Wilderness Area. | NATIONAL MUSEUM OF FOREST SERVICE HISTORY

The day after they arrived at the lake, the party mounted their horses to do some exploring. Schunk had never been to the headwaters of a tiny creek that cascaded down the lake’s steep north slope. He brought Zahnie, Matthias, and four others up “what I would have thought an impossible ascent for the horses,” Zahnie wrote. They poked around high ridges, canyons, and lakes.

A storm caught them near a clump of stunted timberline trees. They started a fire and ate lunch but eventually had to stand “rather silently with our backs to the driving hail, which was hard and thick and soon covered the ground with a layer half an inch to an inch thick,” Zahnie wrote. They had to calm their horses, which had been frightened by nearby lightning strikes.

Later, they found their hoped-for route blocked by impassable rimrocks. They had to cross a lake so deep that the horses were nearly swimming. When they finally made it back to camp, Zahnie wrote, “I could barely stagger from my horse, but I was exhilarated by the grandeur and wildness of the country we had seen.”

Subsequent days were not quite so challenging for Zahnie but nevertheless strenuous. They made difficult stream crossings and rode to distant lakes. They endured more cold and driving rainstorms. They encountered snowfields, rushing cascades, occasional grouse, and plenty of bare rock. When a pair of mule deer scampered hesitantly away, Zahnie speculated that his party was “perhaps the only human beings they had ever seen.”

He constantly compared the forbiddingly rough surrounding country and the serene Lake Solitude. He even reflected that individual water droplets “had not long since been rushing and roaring, twisting and tumbling, foaming their way to this serenity.” And, at the lake’s outlet, they would resume a headlong descent. Like people, he implied, the water cherished the brief respite of peace and wonder provided by the lake. “One could himself know only for a time such serenity, but it was indeed something to know.”

The trip continued with another four days base-camped at Cliff Lake. Zahnie found similar serenity in the massive peaks, a “serene eminence” in the “somber splendor of Blacktooth” Mountain.

“The wilderness had surely been both nourishment and tonic,” he wrote on their return. “It had indeed justified its existence, and not one had returned from this excursion without a keen appreciation of its values, without the earnest hope that the wilderness would always be there.”

These quotes, from an article in the Wilderness Society newsletter that Zahniser wrote after returning to the city, marked his return to traditional forms of work: lobbying, cajoling, and persuading. He was especially good at storytelling, with a hint of rhetoric as in this travelogue. He wanted to show people the wonders of wilderness by chronicling his own tenderfoot journey.

That work was successful; to the surprise of some of his colleagues, Zahniser did indeed help Schunk stop the dam. He did it with the same humility and intensity that would mark his later work, expanding protections from a single lake to a nationwide network of wilderness.

But that humility and purpose — the core tenets of Zahniser’s character, which led to his success as both a lobbyist and a human being — were most evident on this trip. He committed to go, to embrace his ignorance, to withstand the hardships, to seek the joys, to look out for his son, and to celebrate his companions.

In the guestbook at Schunk Lodge, Zahnie gave thanks. The experience, he wrote, “makes one feel grand and humble both. … It was a rare privilege to live for a time in such an environment and with such a group of people. … I trust that I can handle well this investment that the Schunks have made in me and in what I represent. Personally, I have a gratitude that I can hardly express for the kindness not only to me but to Matthias too.”

What was the greatest outcome of the trip? It led to the stopping of the dam and the preservation of Lake Solitude in its natural glory. It eventually led to the Wilderness Act as well, extending such preservation to millions more acres. But it also led to a deep and abiding friendship between the Zahnisers and Schunks.

Zahnie returned several times to Schunk Lodge, once bringing his whole family and another time the whole Wilderness Society Council. In 1957, Edna Schunk wrote of that latter visit, “I know it was a great privilege for us when Zahniser asked if the National Council Meeting could be held here, and for it to have become reality has exceeded all of our wide experiences.”

In the 1964 Act, Zahniser famously wrote that wilderness was a place “untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” But the purpose of preserving these lands was to “leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment” of precisely the type that Zahniser experienced on this trip.

John Clayton, a regular contributor to Big Sky Journal, is the author of several books, including Natural Rivals, The Cowboy Girl, and Wonderlandscape. He also writes the newsletter “Natural Stories;” johnclaytonbooks.com.

No Comments