29 May Homage to a Bygone Time

From 1920 to 1943, hundreds of children experienced the sights and backwoods of Yellowstone National Park from a saddle. The excursions were organized by Valley Ranch, a popular dude ranch east of the park in Wyoming. Intended to provide access to many attractions around Yellowstone, the trips were most extraordinary for their regular forays into the park’s vast backcountry — unique spaces few tourists, even today, are lucky enough to enjoy.

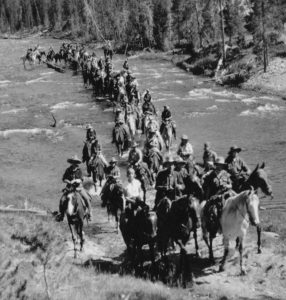

Pack trip groups were required to avoid roadways so as to not conflict with vehicle traffic in Yellowstone National Park. A large party of riders is pictured crossing the Gibbon River below Gibbon Meadows.

In selecting such a wild endeavor, participating children — largely the offspring of Eastern financial and industrial capital — chose an activity that was a vigorous affirmation of American culture, one that eschewed much of the opulence and luxury demanded by many in their economic class. Undertaken partly to instill hardiness and stamina in the privileged children of the economic elite, and partly as an homage to an almost mythic way of life quickly disappearing from a modern America increasingly characterized by crass consumerism, pack trips were an anti-modern recreation for those who were the greatest beneficiaries of modern capitalism.

The record of the Valley Ranch pack trips is a story in which visiting dudes rode through pristine landscapes, slept in the fresh mountain air, and witnessed extraordinary sights from the back of a horse. Yellowstone became just as entwined with the dude experience as learning to ride a salty mountain pony and donning fancy chaps — it was a chance to revel in outdoor life until the tour ended and the children returned East to their schools, dormitories, and city lives.

Irving “Larry” Larom was a product of the East Coast. After graduating from Princeton in 1914, he ventured west with his friend Winthrop Brooks, of Brooks Brothers clothing company. The young men thoroughly enjoyed the experience, so they purchased a ranch on the South Fork of the Shoshone River, about 35 miles southwest of Cody, Wyoming. The business partners named their investment Valley Ranch and were soon inviting dude guests.

Larry Larom managed the Valley Ranch near Cody, Wyoming for over 50 years. Here, he poses by the ranch’s decorative entrance gate.

Distinct from businesses offering routine tours along park roads, many dude ranches sought to provide their clientele with extraordinary experiences unavailable to other Yellowstone visitors. One of the principal activities at Valley Ranch, as at most dude ranches, was horseback riding. Apart from regular day rides in the surrounding foothills, the ranch also offered guests extended pack trips in the mountains and nearby Yellowstone National Park. These outings were casual affairs, without rigid itineraries or big logistical challenges.

A group of girls ready to embark on a pack trip through Yellowstone sits on the steps of Buffalo Bill’s Irma Hotel in Cody, Wyoming. Valley Ranch guests were given the opportunity to acquire authentic Western garb from local shops in Cody as soon as they stepped off the train.

But in 1920, Larom announced that Valley Ranch would begin outfitting annual pack trips for children into Yellowstone and Jackson Hole. With the recent conclusion of World War I and subsequent economic prosperity throughout the Roaring Twenties, dude ranches across the West were poised to reap the benefits of an affluent class of American professionals looking for leisure opportunities for themselves and their children.

Three young women from a pack trip through Yellowstone rest atop Avalanche Peak near the park’s east entrance.

To coordinate the tours, Larom contacted Horace Albright, superintendent of Yellowstone at the time, requesting permission to carry out his ambitious plans. Albright was more than happy to accommodate horseback parties, responding to Larom’s inquiry with resounding approval, writing, “We are exceedingly anxious to get people on the trails and to encourage the use of this great reservation as an all-summer resort. We are particularly anxious to have people go into the out-of-the-way places and take an interest in the wildlife and other natural features of the park.” At a time when the National Park Service was trying to advocate for the parks and encourage their use by whatever means, promoting backcountry horseback tourism was an alluring prospect.

Local cowboys and ranch hands were employed as wranglers and camp cooks on Valley Ranch pack trips. They are pictured at a mess table near one of the camp’s chuck wagons.

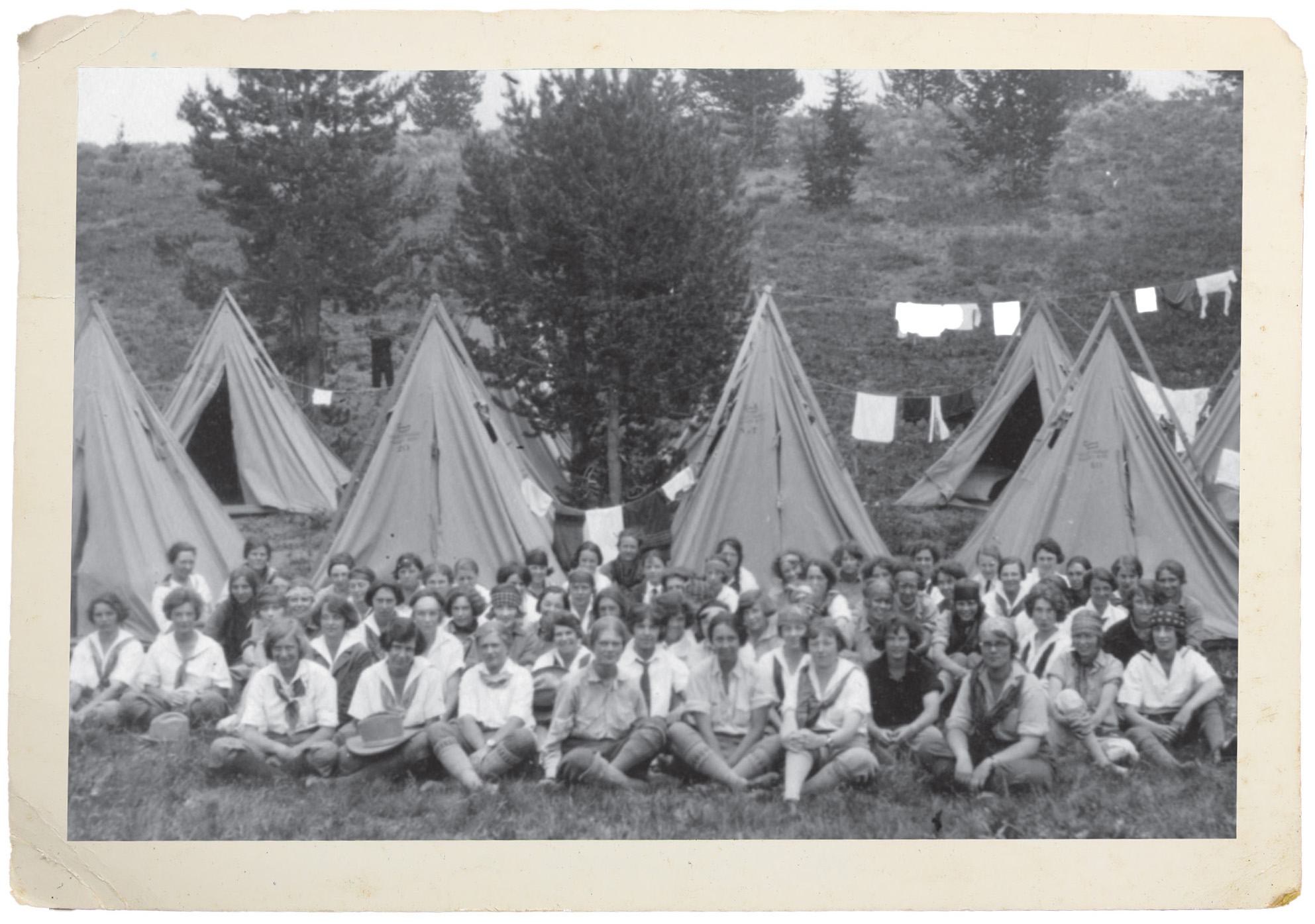

Larom recruited children from Eastern preparatory schools for his Yellowstone pack trips. The excursions — slated to last over 40 days — were seen by their clients as an alternative to the Eastern summer camps frequented by many of the same children. The more informal atmosphere of a Western adventure was a draw for those seeking something different from structured summer camps. “Season by season, the popularity of pack trips through the wilderness increases,” the ranch’s promotional literature touted, “and because it adjoins the wildest, the least explored, most interesting and beautiful among all the wilderness areas in America, it is only natural that pack trips are quite the usual thing at Valley. … They are carefully planned, expertly managed, and represent the very acme of enjoyable and worthwhile Western adventure.” During its heyday, Valley Ranch recruited 30 to 40 teenage boys and girls each year to participate in the summer-long experience.

Pack trips through Yellowstone often followed the Howard Eaton Trail, a route maintained by the National Park Service to allow for horseback travel. It was named after a pioneer of the dude-ranch industry who regularly guided his guests on extended horseback trips through Yellowstone.

Given the flourishing hormonal volatility of teenagers with minimal oversight, the boys and girls traveled separately along their routes through Yellowstone and Jackson Hole, although the two groups occasionally converged for larger camp activities. Itineraries differed each year depending upon trail conditions, available horse pasture, campsite suitability, and the number of riders. The usual schedule started with a training camp outside of Yellowstone, where campers learned to ride, perform camp chores, and acclimate to life outdoors.

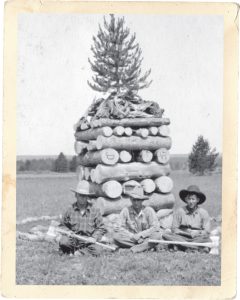

Building large bonfires was a tradition many pack-trip parties observed while camping in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks.

The parties then entered the park via the east entrance, crossing Sylvan Pass above Yellowstone Lake. Upon reaching Fishing Bridge, the pack trips usually turned north into Hayden Valley, paralleling the main travel roads to all the areas of interest on the southern loop. As Valley Ranch’s promotional literature spelled out, “the free, open manner of living, the abundance of wholesome food and water, the opportunity for horseback riding, mountain climbing, and other active sports” all presented these lucky campers with experiences that surely permeated throughout their entire lives.

Chores were a regular part of a summer pack trip. Clothes were washed the old-fashioned way: in a bucket using water collected from nearby streams.

The pack-trip itinerary was planned with multi-night layovers at the best campsites along the route. Children slept in small tipi tents — 6 feet square — allowing room for two campers and their sleeping rolls. There were also striped tents called “pintos.” Inside each, a foldable wooden stool straddled a shallow pit, serving as a bathroom.

Valley Ranch hired about a dozen men to accompany the parties as guides, wranglers, and camp cooks. These individuals were usually local cowboys, and the success of the pack trips largely fell on their shoulders. At the end of the day, these cowboys were responsible for providing for the children’s safety while fostering a fun environment despite whatever adverse conditions backcountry travel brought their way.

Campers enjoyed the opportunity to swim, cooling off in Grand Teton National Park’s String Lake.

Quite different from modern glamping, the pack trips offered by Valley Ranch were intended to teach their young participants how to take care of themselves, tend to camp, and perform needed chores. After all, the ranch did market their youth horseback adventures as an “Educational and Recreational Summer Vacation.” Moreover, these pack trips, and the world of dude ranching from which they were derived, aimed at “stimulating rugged character by simulating the frontier,” as one historian has observed.

Indeed, many attendees found the pack trips healthful and invigorating, and a large number returned for subsequent summers. One parent expressed the benefit his daughter received, writing to Larom, “Phoebe enjoyed her trip in every way and I consider it a wonderful experience for her. I can only praise the way you managed everything and the fine ideals you required them to live up to.”

After covering some 600 trail miles during six weeks, the expeditions ended with a visit to Valley Ranch, where the combined parties participated in horse races, amateur rodeo events, and a barn dance attended by regular dudes and pack-trip children alike. The culminating festivity at the ranch was truly a remarkable sight. As one newspaper correspondent observed:

The setting of this spectacular affair was a beautiful valley, carved by the magic hand of nature, nestled snugly between mountains that seemed to exert themselves in an effort to reach the blue heavens above. O’erhead a soft pale moon played with fleecy clouds, giving to the mountains a peculiar purplish haze in colors that man is infallible to paint. A slight breeze rustled the leaves of the great cottonwoods. In the distance the faint and gentle rippling water, coursing its way down the mountain side, met the ear.

After a few days spent in the tranquility of the ranch, the adventure ended, and the children were spirited away to their homes and schools back East.

Although popular during the 1920s, by 1932 pack trip participation was greatly reduced, reflecting the far-reaching economic consequences of the Great Depression even for well-heeled dude-ranch clientele. Given these new circumstances, the boys’ and girls’ parties were occasionally combined, and the routes shortened to reflect the belt-tightening measures implemented by dude ranches and the broader tourism industry.

A popular campsite for large equestrian tourist parties, Otter Creek Camp was situated on the Yellowstone River a short distance above the Upper Falls.

The trips were discontinued altogether in 1943, although Valley Ranch continued offering horseback tours into Yellowstone for their regular summer guests until 1964. That year, Larom wrote a letter to his old friend Albright, lamenting the decline of equine tourism in the park:

There are no more big trips such as Valley and Eatons used to operate, nor have I had any requests for a pack trip into the park for many years, or heard of anyone else doing so. What few summer trips are nowadays devoted to short fishing trips into the Forest Wilderness areas, and not too many of them from this area. Costs are excessive and most “dudes” are averaging two weeks or less even at ranches. … Too much motor traffic in the park for any horse outfits.

Indeed, many changes in Yellowstone and across the nation contributed to the decline of this unique form of wilderness tourism.

The combined boys’ and girls’ parties, with guides and chuck wagons, pose for a group photo at the Snake River Camp near Flagg Ranch.

Pack trips into the backcountry of Yellowstone are not as frequent as they once were. Present-day visitors are simply less willing to endure the discomfort of long days riding horses and sleeping in tents for over a month. Glamping is a novel trend, but despite what some might claim, backcountry tours on horseback are not quite a luxurious experience. Being cold, wet, sweaty, and sleeping in a crude tent while your back and butt are sore from riding atop a surly nag under the hot sun all day are not what many envision as an enjoyable way to spend precious vacation time. Summer pack trips, for better or worse, are just not as appealing or practical as they once were.

Today’s pack trips into the modern backcountry are usually much shorter, often lasting a week or less. They stress comfortable accommodations, intimacy with nature, and a safari-like Western adventure. While these contemporary outings still may offer the experience of a lifetime, it is safe to say the extensive horseback tours organized by Valley Ranch around Yellowstone and Jackson Hole have largely become relics of a bygone age.

Brian Beauvais is the curator of Park County Archives in Cody, Wyoming. He has written about and given public programs on various topics relating to the history of northwest Wyoming, including wildlife conservation, prospecting, recreational pack trips, historic preservation, ranching, and local art.

No Comments