25 Sep History: Thomas Wolfe’s West

The giant entered Yellowstone National Park squeezed into the back seat of a white Ford Model 81A DeLuxe sedan, arms akimbo, knees spread wide. It was June 27, 1938. The man was 6 feet, 6 inches tall, with medium-length unruly black hair pulled back from his forehead. He was 37 years old, with the beginnings of a bald spot and a paunch. He wore an eight-day-old gabardine suit with two-day-old pants — this crazy trip had already worn through his first pair.

ADMIRING YELLOWSTONE’S OLD FAITHFUL GEYSER DURING HIS 1938 TOUR OF THE WEST. | PHOTO COURTESY OF BUNCOMBE COUNTY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PACK MEMORIAL PUBLIC LIBRARY, ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

His name was Thomas Wolfe, and he was one of America’s best-known writers. Although he was on vacation, he was always collecting material — furiously scribbling notes deep into the night. In this case, he hoped to turn his Western journal into a novel that would change the direction of both his career and American fiction.

Traveling north from Yellowstone’s South Entrance, he saw “the Snake River foaming in its canyon, then a lake with a thick forest round it.” At Thumb Paint Pots, his stream of consciousness noted: “boiling waters, sinister, grotesque, curved like a rhinoceros imbedded moving through hot oatmeal — then the narrow road to Old Faithful, and a bear by privy and the woods, and smoke boiling from the ground…”

A typical auto tourist in Yosemite, Wolfe fed a curious deer. | Photo Courtesy of Thomas Wolfe Photograph Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

Wolfe was the original oversharer. His most famous saying, “You can’t go home again,” could be followed by “after you’ve written a barely disguised autobiographical novel telling all your neighbors’ secrets.” Yet the power of his 1929 Look Homeward, Angel and the 1935 Of Time and the River, which similarly grew from his life in New York City, was his rhapsodic style and ambition to capture the richness of human experience.

Today, Wolfe is little known and often confused with the white-suited journalist and novelist Tom Wolfe (The Right Stuff, The Bonfire of the Vanities). But in his lifetime, Thomas was widely read and often talked about. He wrote eloquent torrents of words, but they usually needed a lot of editing. Was he just an over-bloated, adolescent hillbilly? His biographer David Herbert Donald wrote, “Thomas Wolfe wrote more bad prose than any other major writer I can think of.” On the other hand, Wolfe was idolized by authors Ray Bradbury, Hunter S. Thompson, and Philip Roth; Jack Kerouac said, “Who was the greatest writer? Wolfe! Thomas Wolfe. After me, of course.”

People who love Wolfe love him deeply. In Hollywood, the 2016 movie Genius stars Jude Law as a too-short Wolfe; Colin Firth as his editor, Maxwell Perkins; and Nicole Kidman as his lover, Aline Bernstein. In academia, a Thomas Wolfe Society publishes the Thomas Wolfe Review. All this attention means that Wolfe’s trip through Yellowstone has been analyzed as an example of his near-insane hunger for experience and pondered for what it says about his character and art.

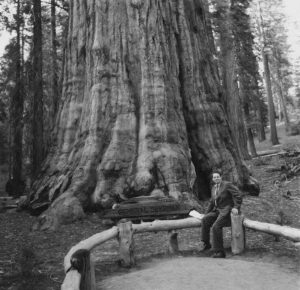

Wolfe’s tour of national parks included posing in front of the world’s largest sequoia tree, “General Sherman,” in Sequoia National Park. | PHOTO COURTESY OF BUNCOMBE COUNTY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PACK MEMORIAL PUBLIC LIBRARY, ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

But what does it say about the West?

Wolfe as a man mirrored Wolfe as a writer: creative, exuberant, undisciplined, lusty, poetic, sentimental, effervescent, stippled with genius, probably a bit too self-centered, certainly larger than life. He had lots of opinions and loved sharing them — but he also loved wandering around public places just for the joy of hearing diverse people talk. In May of 1938, he completed a million-word manuscript, more than 10 times the length of an average novel. After submitting the 5-foot-high stack of paper to his editor, he took his appetites on a Western vacation.

He took the train, as such explorers had done for decades. Wolfe was traveling solo following the end of his relationship with the married Bernstein. He’d been invited to give a lecture at Purdue University in Indiana. To a New Yorker, that was close enough to “the West” to justify continuing to the Pacific. Wolfe saw some friends in Denver and then continued to Portland, Oregon.

At a party, he met Edward Miller, an editor at the Portland Oregonian newspaper. Miller was about to embark on an automobile tour of national parks, and Wolfe got himself invited along.

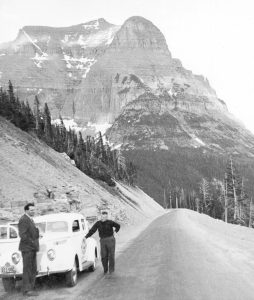

Four days after that, Wolfe, at left, and his companions, Ray Conway and Edward Miller, stopped atop Logan Pass in Glacier National Park. | PHOTO COURTESY OF BUNCOMBE COUNTY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PACK MEMORIAL PUBLIC LIBRARY, ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

Miller’s bosses thought Wolfe, the famous writer on vacation, would make for good copy. But in retrospect, two other factors make the trip even more fascinating. First, the itinerary of the two-week journey included Crater Lake, Yosemite, Sequoia, Grant (now part of Sequoia and Kings Canyon), Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce, Grand Teton, Yellowstone, Glacier, and Mount Rainier. Wolfe had been raised in the Southeast and had already visited the Southwest, so he wrote to his agent, “When I get through, I shall really have seen America (except Texas).”

But even 30 years previously, nobody would have imagined making such a claim, and not only because several of those parks hadn’t yet existed. Back then, the West was defined by cattle ranches, big-game hunting, horseback riding, and fishing. It was action more than scenery. But if you did want scenery, you could find it anywhere, not just behind boundaries drawn by the federal government. This trip was groundbreaking because it effectively defined the West through its national parks.

Second, they visited these parks by car. Ray Conway, an automotive lobbyist, proposed the trip. He managed the Oregon State Motor Association, an affiliate of the American Automobile Association. Conway’s pitch to Miller: “By driving about 300 miles a day, it would be possible to visit all [11 of] these parks within the space of a two-week vacation.” With a World’s Fair coming up in San Francisco, Conway wanted to prove to visitors that such a trip could be done cheaply.

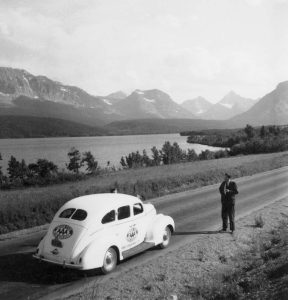

Five days later, Wolfe stood next to his companions’ car, sponsored by an automotive lobbyist, at a lake in Grand Teton National Park. | PHOTO COURTESY OF BUNCOMBE COUNTY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PACK MEMORIAL PUBLIC LIBRARY, ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

Such automotive rush jobs would eventually become a ruling mythology of mid-century American family life. But at the time — amid the Depression, when vehicle breakdowns and dirt roads were common — it was a radical idea. “It sounds crazy,” Miller recalled telling Conway.

It took Wolfe just a single day to agree. They arrived in Klamath Falls, Oregon at 10:30 p.m., having driven more than 400 miles since sunrise, while also spending three hours exploring Crater Lake. Wolfe referred in his journal to “The gigantic unconscious humor of the situation … ‘making every national park’ without seeing any of them — the main thing is to ‘make them’ — and so on and on tomorrow.”

They forged on, indeed. Conway and Miller traded driving chores every 100 miles, but Wolfe, who had never learned to drive, was always consigned to the back seat. Miller and Wolfe both complained about their brutal schedule — always up early and usually arriving at a hotel after dark — and Conway responded, “If you two would spend more time sleeping and less time drinking beer, you’d feel better in the mornings.”

In other words, Conway implied this was work. In this case, you could take the implication literally: Miller and Wolfe were scribbling notes for future writing projects, and Conway was arranging all the accommodations and doing lots of bookkeeping as part of his publicity mongering. More broadly, however, their attitude — early to rise, count the miles, check off the parks seen — captured the American tendency to see a vacation as another form of work; like making widgets, making tourism left little time for fun.

Wolfe mostly seemed to grasp that people and relationships were the stuff of literature, not work or tourism. “The national parks, of course, are stupendous, but what was to me far more valuable were the towns, the things, the people I saw — the whole West and all its history unrolling at kaleidoscopic speed,” he wrote to his agent.

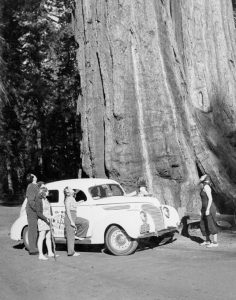

Though the 6-foot-6 Wolfe towered over the 16-year-old girls he’s pictured with here, the trees of Sequoia National Park dwarfed them all. | PHOTO COURTESY OF BUNCOMBE COUNTY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PACK MEMORIAL PUBLIC LIBRARY, ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

For example, in Utah, Wolfe met a “quaint old blondined wag named Florence who imitates bird calls.” In Jackson, Wyoming an amiable gas station attendant said of Wolfe, “My gosh, if I was as big as him, I’d go around knocking people down just for the fun of it.” In Livingston, Montana Wolfe noted “a waitress with a tired face, and yet with charm, sedateness, and intelligence.”

One of the themes of Wolfe’s writing had always been provincialism. He’d grown up in Asheville, North Carolina but studied at Harvard and spent his adult life in New York and Europe. Caught between the hinterlands and urban intellectual society, not fully accepted by either culture, his work instead explored their tensions. Yet, by the time he came West, he had become a New Yorker: He defined the provincial through opposition to coastal elites. In other words, he could see Wyoming or Montana as identical to Asheville in that they were not New York.

Many writers of his era wanted to discuss fascism, communism, or other ideas and ideologies that generated strong opinions. But Wolfe had never been an intellectual writer. He’d written about his family, and then his friends and lovers.

He was now looking for new people and new experiences to fill his next book, but he didn’t seem to realize that practically the only Westerners he met were in the tourism industry. These were manufactured relationships in transient communities — an idea-person might try to argue that this made them authentically Western or even authentically provincial. But Wolfe seemed to be hoping that he could replicate his Asheville people and relationships out West.

The one exception came in the longest park-less stretch of the trip, from Bryce to Grand Teton, through the heart of Mormon Utah and Idaho. Wolfe found “a greener land, and grass in semi-desert fields, and stock and cattle grazing, and now timbered hills in contour not unlike the fields of home… Canaan pleasantness.” He repeated the word Canaan nine times in a single journal entry. It was a tribute to the region’s religiosity but also to the mythic “land of milk and honey.”

Wolfe and Conway’s trip set a standard for what Wolfe called “making every national park without seeing any of them.” | PHOTO COURTESY OF BUNCOMBE COUNTY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, PACK MEMORIAL PUBLIC LIBRARY, ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA

Wolfe loathed the teetotaling Mormon religion and Salt Lake City’s “ugly, grim, grotesque, and blah” temple. He described “Mormon coldness, desolation — the cruel, the fanatic, and the warped and dead.” He referred to village houses as “blistered” or “mean and plain and stunted looking.” But he loved orchards and fertility; he found Utah’s Cache Valley to be “a land of peace and promise of plenty.”

The contrast of landscapes lingered through his time in greater Yellowstone. He said little of the grandeur of the Tetons or the belching power of the geysers. Instead, he described the valley north of Gardiner, Montana as “not so green as Mormon land” and reported with delight that midnight revelers at the Old Faithful Inn (“like a liner shipboard bar — more merriment here and people more prosperous less cultured”) sang the college football fight song, “We don’t give a damn for the whole state of Michigan,” but substituted “Utah.”

Here was a contrast worthy of a great American provincial novel: on the one hand, a “magic valley plain, flat as a floor and green as heaven and more fertile and more ripe than the Promised land,” yet ruled by a religion he found cruel and fanatical. On the other hand, pieces of manufactured culture and community for rootless automobilists seeking scenery on a budget and often being delighted by the wonder of their fellow Americans from elsewhere.

Wolfe never wrote that novel. As the trip ended, he visited friends in Seattle. A cough developed into something worse. Diagnosed with pneumonia, he entered a sanitarium. Continuing to decline, he transferred to a hospital in Baltimore. On September 15, three weeks shy of his 38th birthday, he died of “tuberculosis of the brain.”

Though the novel never existed, I’d like to argue that, in a weird way, its legacy still does. In the cultural question — do novels create culture, or reflect it? — Thomas Wolfe’s West makes a great argument for the latter.

The West is still known primarily through national parks — after all, the TV show about a Montana ranch is called Yellowstone. The region is still defined by the automobile — a few parks have shuttles, but almost every vacationer takes a car. The region is still perceived through the scenery and tourism of what’s sometimes called the “New West,” rather than the work and relationships of the “Old West.”

The West still features a recurring contrast of fertile-if-conformist communities and lively-if-vapid resorts — of what Wallace Stegner called “stickers” and “boomers.” Nevertheless, it is still defined by the New Yorker’s idea of provincialism as a bunch of “red states” whose chief characteristic is their distance from cultural elites.

Wolfe’s next novel might have failed to capture all that. He might have remained too self-centered, too much the drive-by notetaker, too uninterested in ideas, too rooted in Asheville or New York, too caught up in his torrents of words to make a lucid point. He might have been, as Hemingway said, “a one book boy and a glandular giant with the brains and the guts of three mice.”

On the other hand, he might have used his Western experience to fulfill the vision of William Faulkner, who later said, “We had all failed, but Wolfe had made the best failure because he had tried hardest to say the most … he was willing to throw away style, coherence, all the rules of preciseness, to try to put all the experience of the human heart on the head of a pin.”

A regular contributor to Big Sky Journal, John Clayton is the author of several books, including Wonderlandscape, The Cowboy Girl, Stories from Montana’s Enduring Frontier, and Natural Rivals. He also writes the weekly email newsletter “Natural Stories”; johnclaytonbooks.com.

No Comments