28 Sep History: The Journey of the Yalies

At 2 a.m. on June 7, 1896, a Great Northern train pulled into the station at Blackfoot, Montana, bringing three Yale graduates to some of the last great stretches of the fabled American West. The privileged leader of the group was Gifford Pinchot, age 31. At 6-foot-2, with a high forehead and thin frame, he had been voted “Most Handsome” at Yale, where he was nicknamed Apollo. Charged with surveying forestlands, he had organized this trip in his role as secretary of the National Forest Commission.

Pinchot brought along Henry Graves, 26, whom Pinchot had mentored since he was a Yale senior and Graves was a freshman hoping to play quarterback on the school’s football team. Clean-shaven with neatly groomed brown hair, Graves had a diplomatic demeanor that covered his puritanical instincts. (In his forties, once he had gained the power to do so, he forbade whistling in his offices.) Their intern/photographer was Walter McClintock, also 26. With deep-set eyes, a bulbous nose, and a small mouth, he worked in his family’s carpet business in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The previous summer, he’d gone on a Western geological expedition and yearned to get back to the region.

To say that they were Yale graduates is to say that they were at the top of the American hierarchy: wealthy, educated, and well-connected. All three had attended elite prep schools (Phillips Exeter, Phillips Andover, and Pittsburgh’s Shadyside, respectively), and Pinchot and Graves had been members of Yale’s elite Skull and Bones secret society.

By the 1890s, Americans of European descent had been heading to the West for decades. Some, such as Harvard graduates Theodore Roosevelt and Owen Wister, had come from a similarly elite background. But these three Yalies had a unique combination of diverse interests, youthful spirits, and access to levers of cultural influence. Over the next five weeks, they would engage vigorously with the landscape and its inhabitants. What the Yalies saw — and what they didn’t see — matched the triumphs and blind spots of the West’s subsequent history.

At the train station, the men were met by guide Billy Jackson, a tall, slender man with high cheekbones and a large moustache. Jackson had scouted for Major Marcus Reno at Custer’s Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, and over the subsequent 20 years had become a widely acclaimed guide, scout, and packer. His ethnicity was part Blackfeet, and he was also known as Sik-Sik-Ka-Kwan (Little Black Foot). Jackson outfitted the Yalies with horses, and they made the 12-mile trip to his ranch on Cut Bank Creek. (Graves had not ridden a horse since childhood and remained sore for a week.) Close to the gorgeous scenery and abundant wildlife of the St. Mary country, Jackson’s ranch was in what is now the eastern side of Glacier National Park.

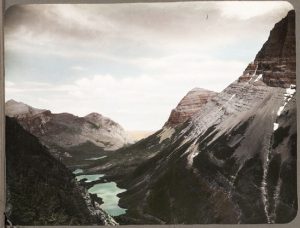

This was what Pinchot had come for: He had heard descriptions of the St. Mary country from another Yalie 16 years his senior, George Bird Grinnell. Grinnell frequently visited the area, always guided by Jackson and Jack Monroe, a white man who was married to a Blackfeet woman. Grinnell called these beautiful mountains the “Crown of the Continent,” and was working patiently to establish the national park.

McClintock and his fellow Yale graduates Gifford Pinchot (left) and Henry Graves (center) came to northwest Montana to experience and shape what they perceived as a final frontier.

Because the Yalies were part of the National Forest Commission, Congress was to pay for their trip. But the appropriation would not become active until July. Pinchot was so eager to duplicate Grinnell’s experience that he came to Montana a month early, paying for himself and Graves out of his family fortune.

Officially, they were doing a “forest valuation survey,” a key component in the then-new discipline of forestry. What types of trees grew in this area, where, and how thickly? How much might they be worth as timber? How soon would they grow back? What did all that imply about how they should be managed? Pinchot and Graves had recently completed similar surveys in Pennsylvania. Such data, which could help experts make management decisions, was lacking through much of the West.

However, the Yalies managed to get in quite a bit of hiking, horseback riding, photographing, and hunting, as well. At one point, they even set out a dead horse as bait for a grizzly bear and hid nearby. Upon hearing shuffling and scratching noises, they crawled forward with rifles ready. Alas, they found only birds.

After a few weeks, the survey took them west of the Continental Divide, to the valley later dammed for the Hungry Horse Reservoir, and then to Swan Lake. Pinchot marveled at the trees: Western yellow pine, Douglas fir, and Western larch — his favorite.

Pinchot and Monroe decided to follow the Swan River toward its source, and then continue south to the town of Ovando, where a stagecoach could return them to civilization. That journey had to be taken by foot, so here the Yalies split up. Pinchot commanded Graves to go back to the train station and head for Michigan to do another forest valuation survey. Jackson, his assignment complete, took his pack train back to his ranch — and invited McClintock to join him.

Another Yalie, George Bird Grinnell, named the 10,052-foot Mount Jackson after the guide, Billy Jackson, who took him there in 1891. | Steven Gnam

To Graves, the Montana experience represented a wonderful opportunity to do real forestry work in the field. At the time, the only professional American foresters had studied in Europe. While Pinchot and Graves had each made pilgrimages to the European capitals of forestry, they both found the European approach too theoretical. European eggheads supervised carefully manicured forests in long-settled areas. America’s forestry would have to be more practical, more rugged. Northwest Montana offered just this sort of experience, and Graves thrived in it.

The next winter, Graves would be offered a job as manager of the Boston Municipal Parks Service. It would take advantage of his administrative skills in a high-profile position: The legendary Frederick Law Olmsted had recently designed many Boston parks, linking them with Harvard’s famous Arnold Arboretum. But the job would be landscape architecture, not forestry. Pinchot extolled the greater value of the latter discipline. Compared to the humdrum manicuring of parks for urban dwellers, forestry was about sustainably meeting the nation’s demand for timber, while maintaining vast stretches of unsettled land.

On the other hand, the problem with forestry was that even the gifted, ultra-privileged Pinchot was then struggling career-wise. Should Graves stick with him, hoping that paid opportunities would develop? The Montana trip had confirmed his love of forestry’s mission and so the decision was made: He turned down the Boston job for a poorly paid assignment researching Adirondack spruce for Pinchot.

As it turned out, the decision proved a good one for Graves. In 1898, Pinchot became chief of the small federal division of forestry, and brought along Graves as his assistant. Two years later, the Pinchot family endowed the Yale School of Forestry, which appointed Graves as its director. Graves eventually succeeded Pinchot as chief of the U.S. Forest Service and shepherded the agency through a stable decade of growth.

Graves’ experiences and choices also had repercussions for the broader history of the West. The rise of forestry led to increased federal influence across the region, which in turn meant rational development around a paradigm of efficiency. The individualistic Wild West would evolve into a region immersed in bureaucratic rulemaking.

McClintock also experienced a life-transforming trip, thanks to Jackson’s invitation. He spent the rest of the summer amid the Blackfeet, enraptured by the romance he saw in their fading traditions. Ethnography, rather than forestry, would be his ticket to the West.

Billy Jackson

For more than a decade, McClintock returned to the Blackfeet Reservation, bringing increasingly sophisticated camera equipment. He shot thousands of images of Blackfeet in traditional dress. Adopted into the tribe, he gained rare access to Blackfeet daily life, as writer Allen Morris Jones notes in his 2018 Big Sky Journal profile on the photographer. McClintock showed his photos internationally, published a book of Blackfeet stories, and commissioned a Blackfeet opera based, in part, on his recordings of tribal songs.

McClintock’s choice was rewarding for himself, and impactful for the West. By popularizing images of traditional garb, leather, and beads, he helped freeze in time this image of the Blackfeet, and Plains Indians in general. In McClintock’s slides and, thus, in the public imagination, an Indian is always wearing a headdress, never a cowboy hat; always solemn, never joking; and always gathered in a campfire-lit tipi, never an electrified cabin.

The trip was life-defining for Pinchot perhaps most of all. His journey through the Seeley-Swan with Monroe was a genuine wilderness adventure. At various times they forded dangerous streams; ran out of food; clambered over endless deadfall; were nearly devoured by mosquitos; baited, tracked, and killed a bear; and had to beg a rancher for a ride to town. “It was a gorgeous trip — the best I ever made on foot,” Pinchot later wrote. On this journey, he discovered an inner hardiness, leadership skills, and respect for a holistic nature. All these lessons proved valuable in the rest of his assignment with the National Forest Commission, especially in his collaboration with naturalist John Muir along the shores of Lake McDonald.

Pinchot’s experience, too, had historical implications. Because the trip gave him the ability to see a forest as more than a resource maximization problem, it fostered the perspective he needed to serve as Theodore Roosevelt’s chief environmental advisor. Furthermore, having experienced hardships in remote places, Pinchot knew how to inspire fierce loyalty among the forest rangers he tabbed to begin building the Forest Service in 1905. Those rangers were predominantly Yalies, graduates of Graves’ new forestry school. Each of them headed out West to make their own journeys, often subtly modeled on Pinchot’s, intertwining the region with the lives and ambitions of elites from back East.

The Yalies parted ways at Swan Lake; Pinchot and guide Jack Monroe penetrated the wilds of the Seeley-Swan country, while McClintock joined guide Billy Jackson on the Blackfeet Reservation. | Steven Gnam

The Yalies didn’t set out to conquer the West. Nevertheless, there’s an interesting relationship between these three individual journeys and the evolution of the region as a whole in the public imagination. To this day, people mirror the Yalies in seeing the West as a setting for outdoor adventure, a useful set of resources to be exploited, or a packaged epoch of quaint, romantic history.

To those of us who live here, each of these views feels a bit shallow. The West is not merely a landscape of obstacles to overcome on your adventure, it’s a place full of people and their communities. It’s not just a set of resources to be managed, it’s a complex ecosystem. It’s not just pictures of romantic, bygone tipis and headdresses (or, for that matter, of mining or homesteading ruins), it’s innumerable, deeply human stories of ambition and loss.

Somehow, the Yalies — despite their advantages, education, curiosity, and the resources at their disposal — missed key aspects of what they were seeing. Graves overlooked the rich forest relationships that lay behind his surveys’ precious data. McClintock failed to understand, or at least to publicly acknowledge, the incredible hardships that his Blackfeet friends were suffering, even as he lived in their villages. (For example, in 1895, Grinnell helped forge a treaty that took the St. Mary country from the Blackfeet. In 1897, thanks to the National Forest Commission, that ceded strip was included in the Lewis & Clark Forest Reserve. Then, in 1910, it was included in the national park, abrogating Blackfeet treaty rights. McClintock never said anything about any of this.) Meanwhile, Pinchot wrote of his Swan Valley trip: “There is a freedom in the pathless woods, if you are there on your own feet and on your own resources.” But of course, he was there with a guide. At their hungriest, he and his guide made biscuits from flour that somebody else had stocked in an abandoned cabin. And Pinchot never even recorded the name of the rancher who gave them a ride out. His brilliant mind obsessed with science, policy, and management, Pinchot often failed to see everyday people and their heroic struggles.

We don’t have to dismiss these men for such failures. None of us is perfect. But their failures offer the opportunity for pause and reflection. As a region, the West sometimes gets trapped in romanticized fables. We’re tempted to blame Hollywood. Or politicians. Or the rural rubes who allegedly can’t handle complexity, who instead imagine their foolish passions imprinted on the landscape. But these faults reside with the elite Yalies as much as anyone.

A regular contributor to Big Sky Journal, John Clayton’s books include Wonderlandscape: Yellowstone National Park and the Evolution of an American Cultural Icon and, most recently, Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands.

No Comments