04 Feb History: Seeing Double in Yellowstone

Most people experiencing Yellowstone National Park at the turn of the 20th century weren’t visiting in person. Back then, travel was expensive and exhausting, involving lengthy train rides and uncomfortable stagecoaches, and people weren’t able to see the park through later media inventions, such as websites, television, movies, glossy color magazines, photo calendars, or even church-basement slideshows. But technology did get them closer to the park — via stereographs.

A stereoscopic view, or stereograph, consists of two nearly identical photographs that are printed together on a card. When you view the card through a stereoscope, your left and right eyes combine the images, giving an illusion of spatial depth. Although stereographs can portray big events, urban scenes, or individual portraits, they have always been especially popular for places of stunning natural beauty. And one of the nation’s most beauteous spots is Yellowstone.

F. Jay Haynes’ Yellowstone stereographs included “Point Lookout and Great Falls” (left), in which he plays with 3-D effects by partially hiding the waterfall behind a cliff. His stereograph “Splendid Geyser” (below) includes a person at the lower right to provide scale and depth.

“Is it not like magic, the way everything stands out in space?” reads the text of a popular 1909 book on Yellowstone stereographs. The book argued that the effect gave “your experience the same reality as that of bodily travel.” Like modern media inventions, stereoscopes brought to wide audiences the visual experiences otherwise reserved only for wealthy travelers.

In the 1830s, English scientist Charles Wheatstone started building mirrored stereoscopes as a way to study the process of binocular vision. His device used mirrors to focus each eye on a different object. Then, because the eyes perceived the objects as being in the same place, the brain merged them. After chronicling this phenomenon and pondering its implications, Wheatstone moved from objects to sets of drawn images, proving that the brain could produce a three-dimensional illusion.

Late in that decade, advances in commercial photographic development processes by Frenchman Louis Daguerre and others led Wheatstone to look into using his new device for photographs, instead of just drawings. As a scientist with many interests and a painfully shy personality, Wheatstone never popularized the idea. But his rival, British scientist and inventor David Brewster, did, creating a hand-held, photo-friendly stereoscope that used lenses instead of mirrors. After that, an American doctor and author named Oliver Wendell Holmes invented — and deliberately refused to patent — a slimmer, less expensive device that took over the marketplace.

A stereoscope, such as this one designed by Oliver Wendell Holmes, helped viewers perceive 3-D effects.

By the late 1800s, stereoscopes were providing one of the most popular personal leisure activities in the U.S. “It was a parlor experience,” says Steven B. Jackson, curator of art and photography at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana, who has studied early Yellowstone photographers. He explains that back then, one might purchase a boxed set of stereographs of a specific exotic location and gather with others to view the images, sharing both the far-off land and the magic of seeing it in apparent 3-D.

Eventually, photographers started making stereographs with special cameras that had dual lenses that were slightly offset, producing two images on the same glass plate, which were then printed side-by-side on cards.

Photographers and commercial publishers liked stereographs because the boxed sets that were created from them boosted revenues. Indeed, the career of famed frontier photographer William Henry Jackson really took off in 1869, when he was commissioned to produce 10,000 stereographs of the West. Best known for his 20-by-24-inch glass-plate photographs of the 1871 Hayden expedition to Yellowstone, Jackson also produced stereographs from that trip, and for decades to come.

Jackson shot stereoscopic images of many classic Yellowstone scenes, including geysers, waterfalls, and the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. In 1871, he often shot the same scenery with multiple cameras. For example, his stereograph of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone may be of historical interest because of the medium, but it presents a scene that many people know from other photographic formats.

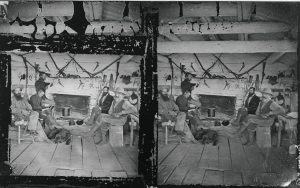

Perhaps more interesting today are Jackson’s unusual intimate scenes. For example, his 1872 stereoscopic interior of Sawtell’s Ranch near Henrys Lake, Idaho, shows men sitting around a fireplace. The three-dimensionality of the dog at their feet, the pots on the fire, and the guns mounted on the wall would have fascinated viewers using a stereoscope back in the day. Today, it’s also a rare glimpse of off-duty explorers relaxing.

In this 1872 stereograph of the inside of Sawtell’s Ranch near Henrys Lake, Idaho, W.H. Jackson captures off-duty explorers taking a break.

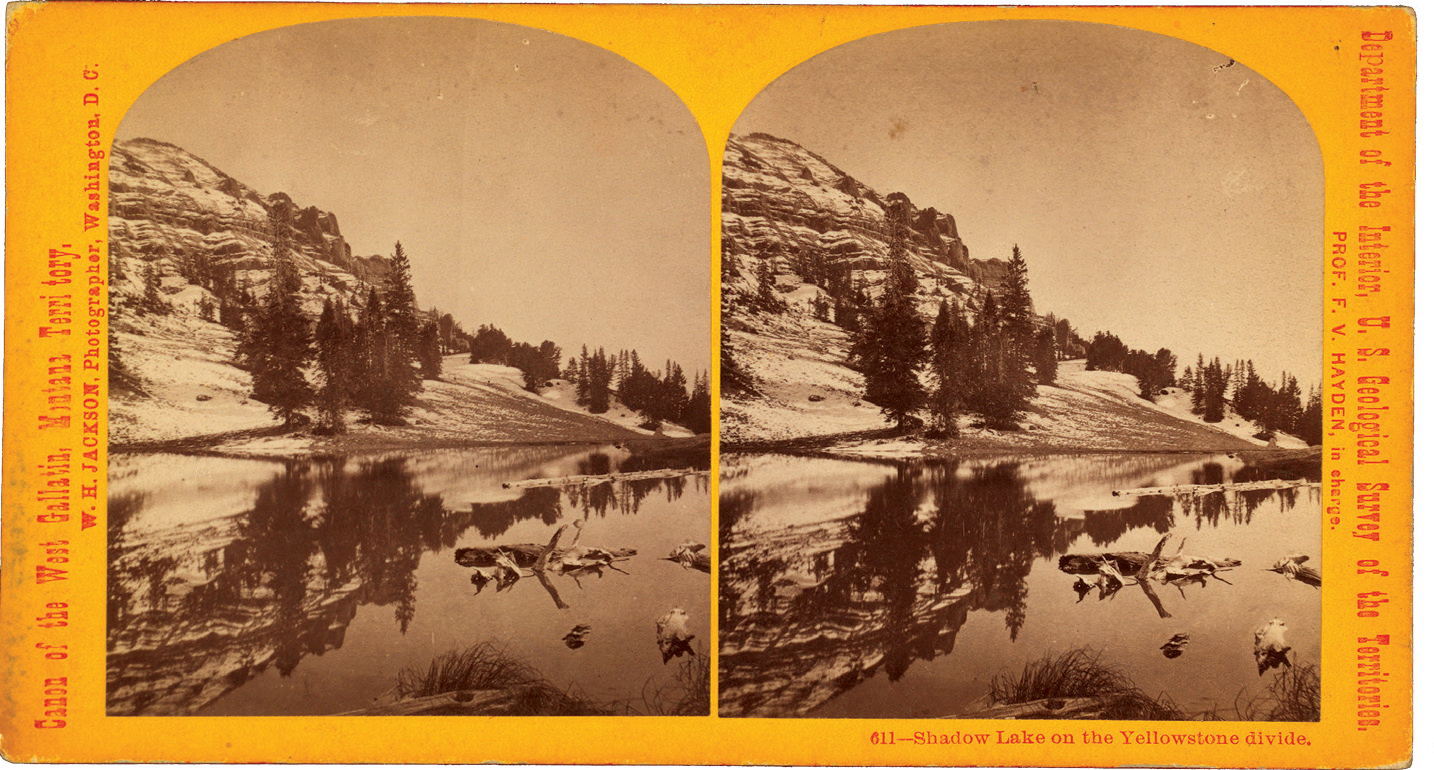

Likewise, Jackson’s “Castle Geyser” from 1874 shows not only the exploding geyser, but also the sinter deposits that form the castle. Their rough textures make for winning 3-D effects. In stereographs, complexity was valuable, with lots of features for one’s eyes to look “around.” For example, Jackson’s “Shallow lake on the Yellowstone divide” from 1872 shows a beautiful mountain lake with grasses and driftwood in the foreground, the reflection of the trees and mountain in the water, and the ridges and snowfields moving up the hill.

Although Jackson gets most of the credit for the photographs taken on the Hayden expedition, there were at least two other photographers present. When the expedition stopped in Bozeman on the way to Yellowstone, Jackson encountered a friend, photographer Joshua Crissman, and invited him to join. At the end of the summer, Crissman had a shorter trip home to his studio and darkroom, and thus published his photos before Jackson did. That made them the first-ever published photos of Yellowstone — and they were stereographs.

Crissman returned for three subsequent summers and later sold his stereo-negatives to other photographers. Although he lacked Jackson’s landscape aesthetic, “Crissman has been overlooked in Yellowstone history,” says curator Steve Jackson.

Another photographer on the trip was Thomas Hine of Chicago. Shortly after Hine returned home, the Chicago Fire of 1871 destroyed all of his negatives. He was able to publish only a few photos before that catastrophic event, including the first-ever photo of Old Faithful erupting — and they were stereographs.

Jackson’s stereograph “Shallow lake on the Yellowstone divide” features driftwood, reflections, and other eye-catching elements.

A “first-ever” status is a fun piece of trivia, but these photos can also be historically significant, says Miriam Watson, the supervisory museum curator for Yellowstone National Park. “Such early images can really be important in national parks, because they help show the landscape and vegetation at the time.” Sadly, the documentation of Yellowstone’s current stereographic records is rather vague. For example, many Crissman photos are dated 1860–1880. It might be a fun project, Watson says, for an aspiring historian to research the collections and date the stereographs.

Famed Yellowstone photographer F. Jay Haynes also produced stereographs. For example, “Splendid Geyser” includes a person at the base of the erupting geyser, not only to emphasize the scale, but also to focus on the 3-D stereo-imaging. The image “Point Lookout and Great Falls” partially hides the waterfall behind a sheer cliff face to give depth for those 3-D effects. And “Rapids above the Upper Falls” shows multiple rapids, with trees and rocks to ponder.

Like his predecessors, Haynes produced complex stereographs designed to reward those studying them in the comfort of their homes. Today’s aesthetic is typically designed to catch viewers’ attention as they scroll past photos on social media, meaning the images need to be simple and clean. But in an era when photos themselves were more rare, audiences preferred them to be more cluttered with content, therefore offering more insight.

After the turn of the 20th century, stereoscopes gradually faded in popularity, as people acquired more options for viewing photographs on postcards, in color magazines, at the movies, and elsewhere. Photographic technology changed. “Stereoscopes faded when Kodak introduced the do-it-yourself snapshot tradition,” says Jackson. After Kodak introduced the Brownie camera in 1900, he says, “You didn’t have to buy a boxed set of Yellowstone photos. You could take your own.”

Thus the meaning of a photograph itself was transformed: It was no longer a substitute for a trip to Yellowstone, enhanced by 3-D effects. Instead, it was a souvenir of your trip to Yellowstone, which could stir emotional associations regardless of its quality or depth.

W.H. Jackson was attracted to the 3-D effects of the roughly textured sinter deposits around Castle Geyser. The result provides a record of what it looked like in 1874.

To this day, stereographs still exist; collectors savor their historical value, and kids wonder at their 3-D effects on indestructible View-Master devices. But now these images are rarely reproduced in magazines, books, or on websites, because there’s no accompanying device to view them. The low demand poses dilemmas for curators. “Stereographs are hard to digitize, because the boards often have a natural curve,” says Watson. “We have to store them vertically upright in archival boxes with supporting material in between.”

Ironically, when you look at today’s newest smartphones, you see dual lenses, as if stereographs are making a comeback. However, these lenses — which are closer together than your eyes — use different focal lengths to provide telephoto and wide-angle images, which a phone’s software automatically stitches together.

As technology marches on, we “see” Yellowstone in new ways. Of course, none of these views come close to matching the in-person experience, but they are yet another example of how an iconic landscape interacts with culture in far-reaching ways.

No Comments