01 Jun History: See America First

The Mountain West in the 2020s has been characterized by increasing crowds. In 2021, Montana’s Flathead County grew by 3.5 percent and Billings was briefly ranked as the top emerging market in the entire nation. By February 2022, the median value of a single-family home in Montana’s Gallatin Valley was $896,000. In 2021, Yellowstone National Park’s 4.9 million visits represented the most ever and a 44 percent increase over 2011; Glacier’s 3.1 million visits were a 63 percent increase. In many areas, restaurants, campsites, and trails are oversubscribed.

Postcards courtesy of streamlinermemories.info

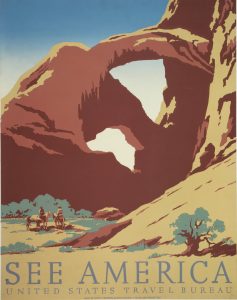

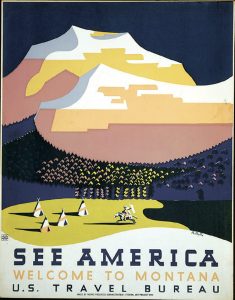

This sudden influx has historical precedent. An early-1900s trend, often summarized by the catchphrase See America First, brought waves of tourists and transplants who defined the region’s culture and economy for decades. If we’re wondering what happens next, we could start by looking at what happened then.

A Utah booster first coined the phrase See America First around 1906. It was shorthand for, “See Europe if you will, but see America first.” The idea, writes historian Marguerite Shaffer in her book See America First: Tourism and National Identity 1880-1940, was to alter the vacation habits of wealthy Easterners. Although economic statistics were imprecise, it was estimated that Americans were spending tens to hundreds of millions of dollars annually in Europe. Most of it, boosters claimed, was spent in Switzerland, where the alpine scenery resembled the Rocky Mountains. The Rockies just needed better access.

Plenty of marketing slogans fail, and this one floundered for a while. But the movement gained traction in 1910, when the Great Northern Railroad used the phrase to promote its hotels in the newly founded Glacier National Park. Then the idea took off in 1914, when World War I blocked tourists’ access to Europe.

The key to success wasn’t marketing strategy, but the way the phrase happened to reflect deeper cultural changes. Consider technological improvements: Expanding railroad networks made American destinations easier to get to — a trend accentuated by the invention of the automobile. Meanwhile, new communications technologies, such as newspaper syndicates, helped establish nationwide markets for both products and stories.

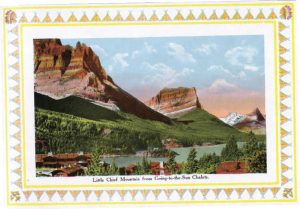

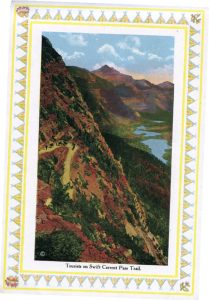

The Great Northern Railroad produced these postcards of Glacier National Park in the 1910s, including Lake St. Mary, Iceberg Lake, and the lobby of the Glacier Park Hotel, each with the marketing catchphrase See America First.

In short, Shaffer writes, America had a new national transportation system and communication network. Thus, America developed new ideas of tourism: Rather than spend your free time at a European resort or local seashore, you could learn about and appreciate your country as a whole. Still grappling with the aftermath of the Civil War, white Americans could find a unifying national identity in stunning Western landscapes.

The 1916 founding of the National Park Service was part of this nationalization of tourism. Yellowstone had been established in 1872, and another 14 parks in later years. Originally unique, dispersed jewels, the parks became part of a nationalized, unified system that told a story about America. For example, Shaffer writes, it positioned Yellowstone “just on the edge of civilization, waiting to be discovered and explored by the tourist.” The park service also standardized management, guaranteed a basic level of comfort, and, perhaps most importantly, gave tourists something to do.

Western landscapes had long been attractive to hunters. But other tourists, especially women, might not want to hunt or camp — or might not know how to do so. What would fill their days? Europe had museums, shops, and formal gardens. In the See America First era, both national parks and dude ranches emerged as ways to aid newcomers in understanding and safely interacting with strange new places.

When we speak of nationalizing an industry, we’re often speaking of economics: a federal government takes over operations. In this sense, the early 1900s tourism industry did get partially nationalized. The federal government ran national parks and supervised concession monopolies. The government also raised everyone’s taxes to pay for roads and other infrastructure essential to tourism.

But See America First was more about nationalization in a cultural sense. Western tourism became a national industry. Thus, the whole country began to feel more invested in the landscapes of the American West. That brought more spending to the region, but also more oversight. Easterners, and the big businesses and bureaucracies serving them, began to have more conflicts with locals over issues like public lands. For example, the history of Grand Teton National Park involves a long battle between wealthy Eastern preservationists and Wyomingites who resisted the nationalization of their local scenery.

Furthermore, U.S. audiences were also investing in troubling interpretations of Western scenery. For example, the unifying national story was often presented as one of the Indian wars: “Conquering the savages” was a story that both Northern and Southern white people could get behind — though, today, many of us abhor glorifying the violent theft of others’ land.

Likewise, when a dude ranch discriminated against Jews, Blacks, or other minorities, that was bad individual behavior — but, when we realize that the ranch was using public lands to articulate a newly nationalized identity, we can see the behavior as more akin to systemic racism. In many ways, See America First was about wealthy white people seeking refuge from a changing world while maintaining their status. That was a problem of inequality: They intended to leave the less fortunate stuck dealing with the problems of the city, while they escaped to allegedly unspoiled realms.

For better and worse, then, See America First transformed the West. It brought the region much-needed revenues during an era of agricultural drought. It also brought growth, which led to more regulation. And, it integrated the West into the national culture and economy: Where class struggles in the late 1800s had centered on regional issues, such as agrarian populism or “Free Silver,” by the mid-1900s, Western class politics resembled those elsewhere.

Some parallels to today are obvious. The COVID-19 pandemic closed off access to Europe just like World War I did. Once-local Western pastimes are gaining non-local adherents — in this case, not only hunting, but also biking, fishing, rafting, skiing, camping, and other outdoor activities. The locations of these activities are often positioned as just on the edge of civilization, waiting to be discovered and explored by the tourist.

Public land managers must respond to that increased demand: Just as national parks in the 1920s shifted from dispersed camping to designated campgrounds, national parks today are shifting from unregulated driving or hiking to reservation systems.

But, more profoundly, we’re also coming off deep cultural and technological changes. Although we don’t think of the internet as a national transportation system, it does let people commute from the rural West to a job anywhere in the nation. Meanwhile, social media represents a pervasive new communication network capable of spreading stories and mythologies across the world.

Thus, our economic growth comes not just in “tourism” (hotels, airfares, rental cars), but in the equivalent of the dude-ranch experience: aiding newcomers as they seek to interact with a new place. In addition to fishing guides and bike tour operators, that’s what glamping is all about — opening up the camping experience to new audiences who may not have learned it from their parents.

Postcard publisher E.C. Kropp collected these and other views of Glacier National Park in a 1910s book titled See America First. Swiftcurrent Pass (top) and Little Chief Mountain (bottom) weren’t just local scenic jewels, but also part of a national story. Courtesy of Mansfield Library Archives and Special Collections

The result is that people nationwide feel more invested in the West. The region becomes less isolated, and more tightly integrated with the wider culture. We see this most clearly in politics: While local Western races used to be about “the person, not the policy,” today, many of us care more about a candidate’s position on national issues such as immigration, abortion, or election integrity. There’s also a lot of talk about income inequality, as wealthy people seem to be fleeing the problems of their former homes. Racial politics are particularly passionate, because we are renegotiating the stories that will unify the nation through the next decades.

History suggests that these changes are not reversible. National park visitation may level off, but it’s unlikely to decline to the levels of 10 years ago. Although some Western newcomers may return to coastal cities once urban cultural opportunities rebound from the pandemic, at some point the growth of a small city becomes self-sustaining, as there are more things for people to do — more recreation, more jobs, more friends, more paths to happiness.

See America First is so woven into the character of Glacier that its gift shop still sells these patches.

Longtime residents can, and should, mourn what we’ve lost, including the empty trailheads, the last-minute trips to a famous national park, and the tightly-knit communities bred of isolation. But history can also train us in the long view. When we look back at the 1910s and ‘20s in the West, few outside of the agricultural sector consider it a time of loss. We see, instead, a time of opportunity: the freedom of automobiles, the romance of dude ranches, the widespread fulfillment offered by expanded access and more diverse economies. A century from now, looking back on today, what might we celebrate?

A regular contributor to Big Sky Journal, John Clayton’s books include Wonderlandscape: Yellowstone National Park and the Evolution of an American Cultural Icon and, most recently, Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands.

No Comments