30 May History: Roosevelt’s Flask

Some 12 years before Theodore Roosevelt’s rapid rise to the U.S. presidency, he experienced a bear hunt that was more troublesome than most of his earlier expeditions. As related in Roosevelt’s book The Wilderness Hunter, he engaged a guide named Griffin, an old man skilled in locating game but “an exceedingly disagreeable companion on account of his surly, moody ways.” Decrepit physically and contemptuous of “tenderfoot clients,” particularly those who wore glasses, the guide left camp chores to Roosevelt.

Roosevelt may have tolerated these deficiencies, but the last straw came when Griffin failed to appear one morning, and Roosevelt, suspicious, rummaged through his bedroll and found his own whiskey flask (“which I kept purely for emergencies”) quite empty. Rather than continue to share a hunting camp with a thief, Roosevelt set out by himself with minimal equipment on a gentle mare, killed a large grizzly, and struggled to pack its heavy, slippery hide back to civilization.

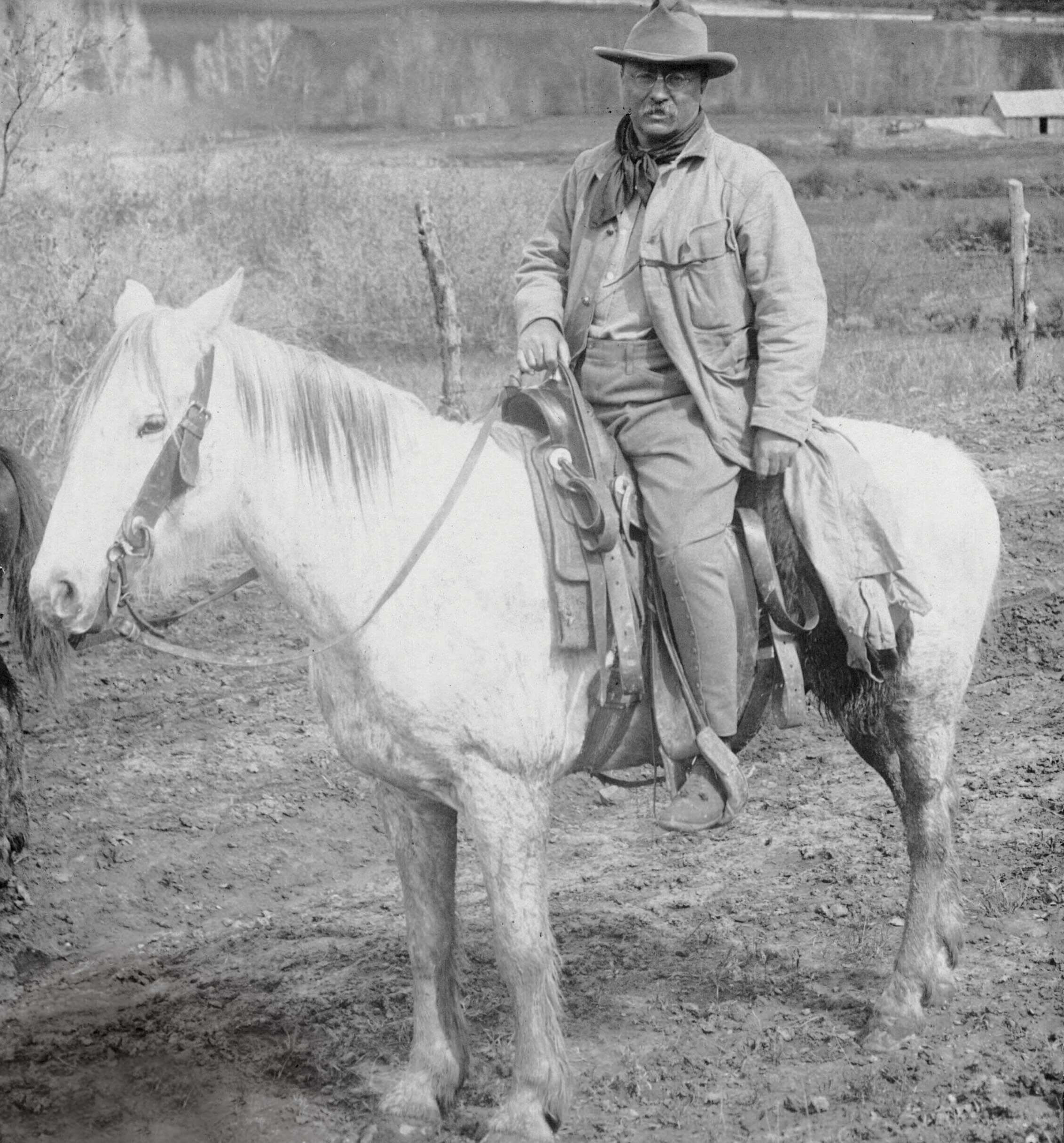

Roosevelt’s love of bear hunting continued into the years of his presidency, including this memorable bear hunt into the Colorado mountains with Jake Borah and John Goff in April 1905. | W384184_1 THEODORE ROOSEVELT COLLECTION, HOUGHTON LIBRARY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

In Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, Roosevelt tells the tale with considerably more detail: a confrontation with rifles occurred, Roosevelt “getting the drop” on the guide, taking the man’s rifle, and promising to leave it by a twisted pine a mile down the trail. For the first couple of nights, fearful the old miscreant might follow, Roosevelt slept well away from his campfire. Reference to his flask in this version is also dismissive, and perhaps slightly defensive. “I had also taken a flask of whisky for emergencies — although, as I found that the emergencies never arose and that tea was better than whisky when a man was cold or done out, I abandoned the practice of taking whisky on hunting trips 20 years ago.”

It seems clear that Roosevelt’s whisky flask was indeed a standby item, not used for sipping around the campfire but perhaps conveying a sense of security. All this might be judged insignificant were it not for the simple fact that the extended Roosevelt family was replete with individuals who were terribly devastated by alcohol. Roosevelt’s brother, Elliot, father of Eleanor Roosevelt (yes, the first lady and FDR were both Roosevelts and distant cousins), succumbed to alcoholism and opiate addictions. One of Roosevelt’s sons, Kermit, who accompanied his father on their 1909 African safari and also the nearly fatal trip to Brazil’s River of Doubt, served in both world wars but eventually died of the effects of alcohol at a military post in Alaska.

Roosevelt is pictured here at the close of his sophomore year at Harvard. | W417689_2 THEODORE ROOSEVELT COLLECTION, HOUGHTON LIBRARY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

The reputation for alcoholism within the greater Roosevelt clan was used against Theodore during the 1912 presidential race, in which, as the third-party candidate of the Bull Moose Party, he unsuccessfully challenged William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson. Tired of refuting the accusation that he was a drunkard, Roosevelt sued George Newett, editor of the Iron Ore newspaper, who had published cartoons depicting him as a drunk. Roosevelt paraded a number of prestigious men through the witness stand, all of whom vouched for his sober nature. Roosevelt won the suit, though he waived financial retribution, instead settling for a public apology.

But before becoming the ultimate “straight arrow,” the Roosevelt we know through history as steadfast morally and physically — as president, conservationist, patriot — did experience a portion of his life in which alcohol played a role. The picture of Harvard University in the late 1870s rendered by historian David McCullough in his book Mornings on Horseback: The Story of an Extraordinary Family, a Vanished Way of Life, and the Unique Child Who Became Theodore Roosevelt refutes any thought that “party school” is a modern phenomenon. Wine, beer, and hard liquor flowed freely, and McCullough writes that a large segment of the student body was far more interested in the perpetual parties than in acquiring an education.

That was not true of Roosevelt: he was a stellar student throughout. But there’s evidence he occasionally succumbed to the atmosphere around him. And that’s where the influence of a caring, compassionate, and bluntly honest friend may have come at a key point in Roosevelt’s life.

Henry Minot was Roosevelt’s best friend at Harvard. Indeed, after Minot’s departure for law school, Roosevelt lamented that he had few, if any, close friends at the university. Minot shared his interests, especially in ornithology, and the two joined in various scientific quests. After Minot’s departure from Harvard, the two stayed close, writing frequently.

Brad Greenwood, a descendant of the Minot family, and his wife, Lorraine, are Paradise Valley residents who provided fascinating correspondence between Henry Minot and Theodore Roosevelt. | Photo by MELANIE MAGANIAS

In her article “Letters from Teddy” (The Montana Pioneer, January 2020), Karen E. Davis relates the fascinating history of the Minot family, New England blue-bloods, and Henry Minot himself, one of its most accomplished members. Equally interesting for Montanans is a local Minot family connection: Brad Greenwood, an artist and artisan who creates custom furniture, is a Minot descendant living in Paradise Valley, south of Livingston. Through the Massachusetts Historical Society, Greenwood became aware of boxes of letters generated within the Minot family, a trove containing extensive correspondence between Henry Minot and Roosevelt, revealing their devoted friendship. Greenwood is to be thanked for making this treasure available to Big Sky Journal. A thorough study of this correspondence could provide ample fodder for a graduate school dissertation.

Davis wisely pinpoints a particular letter written in December 1879 by Minot to Roosevelt. Minot begins, “Dearest Ted, After much hesitation, I am going, for once, to write to you seriously.” After that rather cautious beginning, Minot explains that the moral atmosphere at Harvard was one he could no longer stomach and was a reason for his departure from the university for education elsewhere. But the rest of the letter is one of the most direct, harsh, and thorough dressings-down one will ever read of a friend to a friend. Minot throws Roosevelt’s behavior at a particular party back into his face. He charges him with engaging in a silly argument, in gross talk in front of a woman, and judges his friend to have been perhaps not actually drunk but “alarmingly far gone.” He brings Roosevelt’s father, who’d passed away two years earlier, into the mix, perhaps the unkindest cut of all for Roosevelt idolized his father (who was, in fact, an incredibly impressive individual). Much of Roosevelt’s distress and occasional depression while at Harvard can be attributed to worries he could not live up to his father’s example.

This is a letter of tough love in spades. Minot begs forgiveness for “attacking … as severely as you, unconsciously, have wounded me.” Bluntly put, Minot says in this letter that if Roosevelt continues down a particular avenue, the two will no longer be friends.

Greenwood holds a piece of the treasure trove of family history discovered with the help of the Massachusetts Historical Society. | Photo by MELANIE MAGANIAS

When someone receives such a thorough and candid negative critique from a friend, it seems all too likely that the friend on the receiving end would terminate the relationship in anger. It’s difficult not to become defensive when criticized in such harsh and personal terms, and even if some of the proffered advice is taken, friendship and trust are likely to cease. However, it is testimony to Roosevelt’s character that such a defensive reaction did not occur. The two remained friends, though geographically distant ones. When Roosevelt experienced one of the greatest traumas and sorrows of his life — the death of his mother and wife in his home on the same day — Minot wrote to him with tender sympathy (just as he had done years earlier when Theodore Roosevelt Sr. passed away).

Roosevelt replied to Minot, calling him fondly by his nickname “Hal,” on February 21, 1884:

Dear Old Hal,

Your loving and heartfelt words of sympathy were very welcome to me, for my heart was nearly breaking. As yet I can scarcely bear to be long with anyone; but in a short time I shall wish to see much, very much, of you, my dearest friend.

Yours ever, Theodore Roosevelt

Did Minot’s letter of criticism cause an immediate change in Roosevelt’s behavior at Harvard? Not completely. McCullough writes of occasional fits of depression, often related to his father’s death, in which drinking was involved. During one such episode, Roosevelt wrote of being little worthy of his father, feeling “a hopeless sense of inferiority to him; I loved him so. … But with the help of God I shall try to lead a life such as he would have wished …” The next page of the diary contains lines heavily blotted out but reveals the discernable, “angry at myself for having gotten tight …,” indicating shame at having come under the influence.

But this we know: Roosevelt, unlike so many in his extended family, never let alcohol control his life and eventually became a near “teetotaler,” one who partook while in the White House an occasional mint julep as a rare and enjoyable indulgence. It would be historically and intellectually dishonest to claim the harsh but loving critique sent to him by his friend Minot caused a major change of direction in Roosevelt’s life. We have no hard evidence of that. But we know that a close friend’s honest appraisal is never taken lightly. And we can be thankful that Roosevelt received one at such a critical juncture in his life.

Dan Aadland holds a doctorate in American studies from the University of Utah and is the author of ten books, including In Trace of TR: A Montana Hunter’s Journey and Sketches from the Ranch: A Montana Memoir. He and his wife, Emily, raise horses and cattle on their historic ranch near Absarokee, Montana.

No Comments