01 Aug History: Pictures of the Past

Former Montana resident Roland W. Reed Jr. [1864 – 1934] finally received recognition for his life’s work in a gallery bearing his name almost 100 years after he slipped on a banana peel, leading to his untimely death. Little is known of the photographer — a contemporary of Edward S. Curtis — whose self-directed, self-funded campaign, Photographic Studies of the North American Indian, spent almost a half-century in storage.

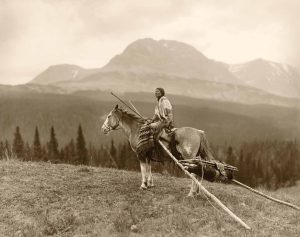

Roland Reed kept notes on many of his photographs, including Lazy Boy, circa 1912: “Indians such as Lazy Boy fought the white man for over one hundred years. They were trying to keep their hunting grounds from being broken up and ruined for the Indian mode of living.”

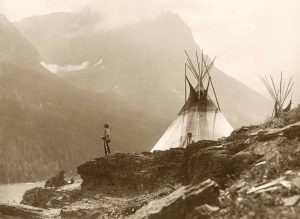

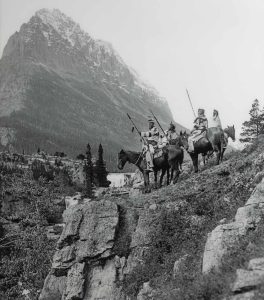

The Eagle, an iconic image of three members of the Blackfeet Nation standing on a rocky outcrop scouring for prey in northern Montana in 1912, is a shining example of Reed’s contribution to the nation’s history. In fact, the powerful visual gripped the attention of Jace Romick, a photographer and gallery owner in Colorado, so much so that he sought out Reed’s collection and bought it in 2021.

The Roland Reed Gallery in Steamboat Springs, which opened in 2022, bears testament to a man who made it his purpose and passion to document the traditions and customs of Indigenous tribes, including the Anishinaabe (Chippewa/Ojibwe) in Minnesota; the Pikuni Blackfeet (Piegan), Northern Tsitsistas/Suhati (Cheyenne), and Kainai Blackfoot (Kainah/Blood) in northern Montana and southern Canada; and the Diné (Navajo) and Hopi throughout the Southwest. He spent the largest portion of his time — and captured most of his images — in Montana, where he made his home for many years.

Woman with Travois shows the typical A-framed design used by the Blackfeet Nation to move their loads.

“As a photographer, we hope our images will evoke emotions within those viewing them,” Romick says. “I believe that was Reed’s intent, and as someone who values our lands and our people as I understand Reed did, I want to honor that legacy with integrity.”

Born in 1863 in the Fox River Valley of Wisconsin, Reed was raised in a log cabin neighboring the Menominee tribe and often referred to his exposure to their culture in his journals.

As I watched them file along the forest trail, I longed to join them, and as I grew into manhood and left my native state, the call of those old friends of the forest and lakes never left me. I could ask for no greater honor at this late date to meet and shake the hands of those fine Indian boys who passed my forest home so many years ago.

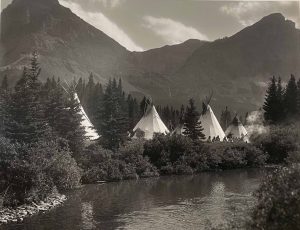

Reed described his image Up the Cutbank as typical of a Blackfeet Nation camp, where water was close at hand to drink, cook with, swim, and bathe in.

Upon completing his early education, Reed left Minnesota to work for the Canadian Pacific Railway, a job that took him to the far reaches of the West and amplified his affinity for Native Americans. Reed had artistic talent and garnered a reputation for sketches and portraits of the people and places he encountered along the way. It earned him a job in the 1890s with the Great Northern Railway documenting the life and ways of the Native peoples of the Plains.

While walking through Havre in 1893 he met Daniel Dutro, a Civil War veteran, prospector, and photographer. The encounter changed his life’s trajectory. Dutro persuaded Reed to swap crayons and paints for a camera and offered him an apprenticeship. Reed became a partner in Dutro’s studio and the duo built a successful reputation for portrait photography.

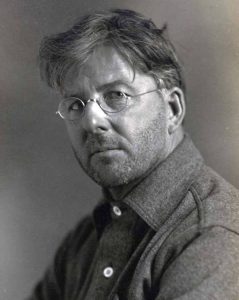

This self portrait of Reed from 1912 was taken during his time living in Kalispell, Montana.

Wanderlust ran deep within Reed. In 1897, he left Montana for a year to photograph the Klondike Gold Rush in Alaska for the Associated Press. For the subsequent decade, he continued with his portraiture work and opened studios in Minnesota, where he could be with family.

He was fascinated by pictorialism, an artistic movement developed in Europe in the 1860s that focused on storytelling through imagery using tonality and composition, rather than the realistic portraiture more typical of the time.

By 1907, an innate calling to document what he and many others believed would be the lost traditions of Indigenous peoples led him to fulfill his life’s passion and purpose. Equipped with a camera the size of an apple box and 11-by-14-inch glass-plate negatives, he closed his studio and spent over a decade immersed among a handful of tribes, some more welcoming of his presence than others.

Reed said the war bonnet worn by this chief was a symbol of achievement, depicting courage and worthy deeds.

His most prolific work was in Montana, among the Blackfeet. When Glacier National Park was designated in 1910, Reed was hired, along with several other artists including Charles M. Russell, to capture imagery of the area’s beauty and people as part of the See America First campaign.

An article published in The Kalispell Bee on January 10, 1913, read:

Roland Reed is perhaps the peer of any artist in the world in his own line. For years he has made a study of the ways of the North American Indian, has lived and worked among them and in his time secured some of the most wonderful pictures ever taken of them. His collection will someday be the most valuable of its kind in the world and will net Mr. Reed a fortune. The finest of this splendid collection are now displayed in the windows of the Kalispell Mercantile Company and there is hardly a moment of the day that a crowd may not be seen studying these masterpieces of art.

Although a handful of his photographs were purchased by National Geographic and used for postcards, Reed shunned significant commercial gain from his work. His priority was to educate the white man about tribal life and traditions. Reed could take weeks, even months, to capture an authentic representation of the subject’s historic way of life. Slowly, but surely, his fastidious reputation earned the trust of those he photographed.

Echoes Call represents the custom of a tribal member standing with his face toward the sunrise, voicing a short prayer to the Great Spirit.

In a letter to H.R. Foster of The Minneapolis Journal in 1923, Reed wrote, “I have been accepted as a member of the secret fraternal order of the Blackfeet called Big Medicine Lodge. Upon my initiation in this lodge, I was given an Indian name meaning Big Plume by which I am known among my Indian friends.”

Reed intended to share his photography in slideshows and educational presentations, a goal he failed to realize, but he did exhibit at the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, California in 1915. Charles Lummis, a founder of the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles (now part of the Autry Museum of the American West), said, “[Reed] has a collection of Indian photographs which would make Curtis turn in his grave if he had got to that turning point. I have looked them over twice, and they are marvels not only of artistic beauty but historical truthfulness.”

Before he started a photography apprenticeship in 1893 in Havre, Montana, Reed first earned a reputation as a portrait artist using crayon and watercolor.

Reed fell short of achieving his intended purpose. During a stop in Colorado to visit friends, he slipped on a banana peel, and three days later, he developed inflammation of the spinal cord and contracted double pneumonia. He died on December 14, 1934, at St. Francis Hospital in Colorado, leaving his personal property to his cousin Roy Williams.

Williams carried out 2,500 educational presentations using Reed’s work, but upon his death in 1949, the entire collection went into storage. It remained unseen until brothers Leon and Wes Kramer, owners of the Kramer Gallery in Minneapolis, purchased it in 1978. The pair retired in 2010, and the collection was again stored until Romick purchased it in 2021.

“This field of work is so dominated by Curtis, so to have another body of work from the same timeframe by another photographer is significant,” says Seth Hopkins, executive director of the Booth Western Art Museum in Georgia. “These are important images being shown at the gallery and to collectors of Western art.”

Landmark, circa 1912, was taken in Glacier National Park and used in a frontispiece for the book Enchanted Trails of Glacier Park by Agnes Laut.

Reed’s haunting images have since captured the attention of a contemporary new audience. “I am a descendant of the Blackfeet tribe from Montana,” says gallery visitor Leticia Uzeta. “I hold great pride in my heritage and find it rare to see Native tribes portrayed in a way that honors them authentically. These images depict their way of life before being stripped of everything. They are a great reminder of why we call ourselves Niitsitapi [meaning, ‘the real people’].”

Romick feels what he calls an eerie sense of responsibility for the collection of around 120 glass-plate negatives and a host of personal artifacts. “To think these plates survived demanding journeys on horseback and decades in storage, and they’re still in such fine shape is amazing,” he says. “I feel accountable to Reed to honor his legacy and display his work as he intended, for generations to come.”

Highlights of the collection can be viewed online at rolandreedgallery.com and in person at Roland Reed Gallery in Steamboat Springs, Colorado.

Scottish-born Suzi Mitchell is a freelance writer who lives in Colorado with her three children, spoiled dog, and nonchalant cat. When not writing about artisans and architecture for publications on both sides of the Atlantic, she paints and plans to publish a series of children’s books.

No Comments